How the Left Got Fucked, part 3

Occupy: the left's dying gasp.

Let’s be clear: austerity is a capitalist’s wet dream. The economic protections for workers that governments put in place (often under threat of revolt if they don’t) are barriers to the accumulation of capital. Thus, while it might have looked like the global financial crisis triggered by the housing bubble in the United States would have been a threat to global capitalism, it was actually exactly the kind of crisis it desperately wanted. Whether or not it was directly engineered, it set into motion terrifying transformations in every “developed” nation in the world, ensuring that neoliberal capitalism would have no significant challenge from the left or right until Donald Trump.

Note: This is the third in this series.

I drunkenly stumbled out of a gay punk bar on a drizzly Tuesday night in Seattle to a strange scene filling the streets. Hipsters, queers, and a motley assortment of others were everywhere, shouting, drinking openly despite the law, and dancing to the music playing loudly from a parked car.

Seattle’s never been known for spontaneous public joy. Even when its sports teams win important games, the most you might ever witness from its local fans are a few car horns sounding sporadically as drivers return to their suburban homes. It was unfathomable, then, that hundreds of people famously renowned for their ironic distancing from anything approximating emotion were acting this way.

The year was 2008, and that Tuesday was the first one after a Monday in November, and we’d all just learned Barack Obama would be the next president of the United States.

The previous eight years had certainly been depressing. During the two terms of President George W. Bush, the entire shape of American society had change thanks in no small part to the “War on Terror.” Years of bizarre and ever-increasing security measures, a laughably comic-yet-serious color-coded terror threat meter, and constantly expanding foreign wars each added to the general sense most of us had that the America we once knew no longer existed.

And this was just what those who weren’t really paying attention noticed anyway.

If you were a leftist at the time, the daily sense of dread was even more crushing. The Green Scare had been in full force for several years by then, and we’d all seen the documented reports of anti-war groups and anarchist cells infiltrated by FBI agents. Added to all this were the countless moments in Washington D.C. where members of the supposed opposition party fell in line with whatever new funding proposals and security expansions the Republican president demanded from them.

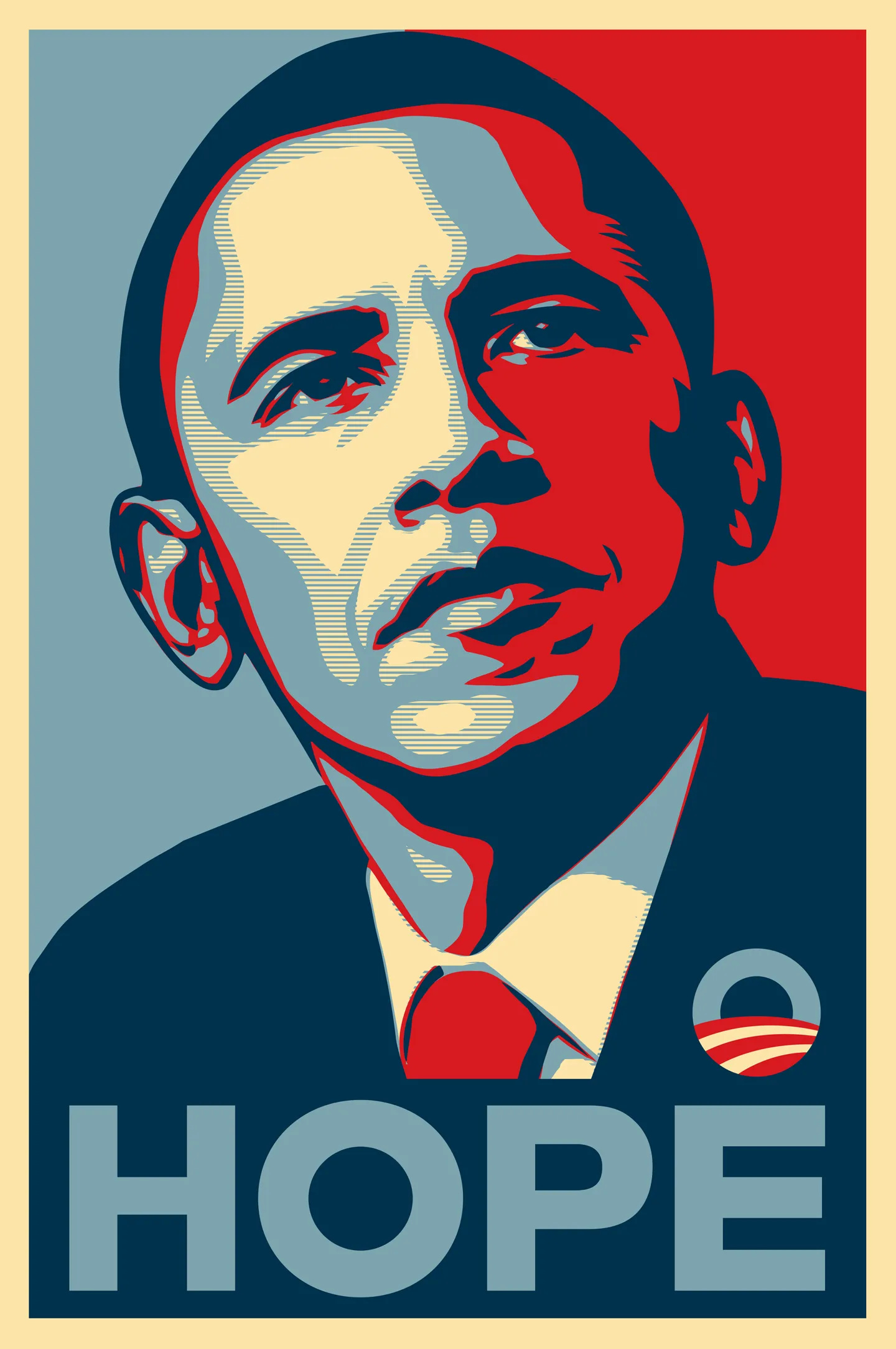

This all explains why the energy from those street celebrations felt like a contagion of hope. Well, that, and because that’s what the posters told us we were supposed to feel.

It probably won’t surprise you that I didn’t vote for Obama. And maybe it also won’t surprise you that the people I told this to both before and after the election were both perplexed and a little upset about my decision.

But something that will also not surprise you now, but absolutely surprised me at the time, was how many of those people then suggested there must be some degree of “racism” in my refusal to vote for him. And even when I mentioned I’d voted instead for the Green Party’s nominee (Cynthia McKinney — a black woman), their judgment remained unquestioned.

That is to say, it was during Obama’s election campaign that I first began to encounter the new framework of identity politics that would soon go on to supplant all other leftist frameworks in the United States. Something was changing on the ideological level of political discourse, and it was spreading very fast. Suddenly, people who’d barely had a political thought in their entire lives were learning to find the unexamined racism in those around them — whether it was actually there or not.

I don’t think I can really overstate how confusing and bizarre this shift seemed. People I’d known for years as hopelessly apolitical had suddenly got politics the way others got religion, and they’d speak with the same false certainty seen in new converts everywhere. Yet these were the very same people who couldn’t be bothered with anything beyond a simple “Bush is bad” statement just a year prior, let alone any sort of deeper discussion about the expansion of state power or the ills of capitalism.

In hindsight, it’s much easier to notice this moment for its historic importance. The Democrats — and Barack Obama in particular — had hit upon a new political strategy based not upon reasoned argument and a coherent platform, but instead upon morality and the desire to be “good.” Over the next sixteen years, another new “Left” would arise, one that could fully sublimate populist opposition to capitalism and state authority and rechannel those revolutionary desires into endless arguments about identity and oppression.

And tracing the ways they managed this complete takeover — and I mean “managed” in its strongest sense — gives us the key to understanding how we might one day be able to unfuck the left. And for this, it’s best to start with the final, dying gasp of authentic revolutionary expression against capitalism in the United States: Occupy.