“If you oppose the political ideology of which I am a primary architect, you are a fascist.”

This is how we can summarize the latest editorial by Judith Butler in The Guardian, published 23 October: “Why is the idea of ‘gender’ provoking backlash the world over?”

Amusingly, the person who is best known for proposing that sex is a false and socially-constructed division of human beings instead posits an even harder division. In her piece, she proposes there are two sorts of people: those on board with the recently-created gender ideology she helped create—or those siding with fascism.

The essay—characteristic of much of her other writing—is quite circular. She sets up several strawmen, knocks them down clumsily, and then conflates multiple ideologically oppositional frameworks together to put forward her primary thesis, that those who oppose new conceptions of gender are fascist:

“Anti-gender movements are not just reactionary but fascist trends, the kind that support increasingly authoritarian governments.”

We have of course seen this very same thing occur with other aspects of Woke ideology. Many Antifa groups in the United States now label those who oppose government-enforced vaccine mandates as “fascist,” despite the fact that at the core of many of those critiques is an opposition to increased state power. Likewise, even black Marxists with long histories of struggle against racism are labeled “fascist” for opposing the current dogma of “Kendian” anti-racism, just as leftists who supported Brexit in the United Kingdom or who voted for third party candidates instead of Clinton or Biden in the United States were seen as supporters of fascism.

There is something much bigger happening here than merely a discussion about trans identity or whether or not institutions should fire white people in order to make their workforce more “diverse.” Just as the meaning of “woman” and “racist” is undergoing a significant shift, so too has “fascist.”

“Intersectional Imperialism”

Once describing a specific totalitarian arrangement of society in which the masses fall in lockstep with a powerful leader, police each other for errant thought, and mobilize into a militaristic war machine, fascism now has come to describe all who resist the “neo-liberal” reconfigurations of identity, state power, and mob violence.

Neo-liberal isn’t the word I would necessarily choose. It is Butler’s word, and her employment of the term helps us understand something I don’t think she intended.

For this reactionary movement, the term “gender” attracts, condenses, and electrifies a diverse set of social and economic anxieties produced by increasing economic precarity under neoliberal regimes, intensifying social inequality, and pandemic shutdown. Stoked by fears of infrastructural collapse, anti-migrant anger and, in Europe, the fear of losing the sanctity of the heteronormative family, national identity and white supremacy, many insist that the destructive forces of gender, postcolonial studies, and critical race theory are to blame.

And

“The vanishing of social services under neoliberalism has put pressure on the traditional family to provide care work, as many feminists have rightly argued. In turn, the fortification of patriarchal norms within the family and the state has become, for some, imperative in the face of decimated social services, unpayable debt, and lost income. It is against this background of anxiety and fear that “gender” is portrayed as a destructive force, a foreign influence infiltrating the body politic and destabilizing the traditional family.”

Butler admits that there is a significant economic and societal disruption occurring throughout the world tied to “neoliberalism,” though here I would clarify that these disruptions were identified as a core mechanism of capitalist “revolutionising” by Marx and Engels. That is, what neoliberalism is doing is not new, but rather what Capital always does and must do in order to create new markets and ways of exploiting labor.

What she does not admit, however, is where that transformative force is coming from nor which side neoliberal politicians and governments take in the arguments over this new conception of gender. The major political, economic, and military power behind neoliberalism is the United States, which is currently led by a political party which has repeatedly supported these newer conceptions of gender over older conceptions of sex. As a matter of fact, the Biden administration has made “progressive” gender ideology a key point in foreign policy.

Here I’d like to refer you to the great work of N.S. Lyons, especially this essay detailing how the State Department has begun formulating a kind of globalisation of American Woke ideology:

There are still plenty of countries out there – in fact, a vast majority of them – who think intersectional gender theory and other fruits of the New Faith are in essence stark raving mad, and are also rather attached to keeping their own cultures and traditions.

So even if you are a strong supporter of LGBT rights, feminism, or other liberal-progressive ideals (and yes, many countries around the world of course do treat LGBT people, women, and racial minorities terribly), it is still worth considering the practical consequences of Intersectional Imperialism. If the West makes ideological conformity an integral requirement for joining, receiving aid from, or even working with its Democracy bloc (as Blinken has implied), then many of these countries are liable to flee into the arms of China and other genuinely authoritarian but ideologically non-missionary states, despite the security concerns they may have.

The problem here is that the United States has identified Woke conceptions of gender as a political tool, part of its civilising mission to the rest of the world. With the “progress” of capitalism now comes the “progress” of American views on gender, which are hardly themselves settled or even fully formed.

So when Butler suggests that those resisting these new conceptions of gender are reacting already to societal disruption, she isn’t wrong at all. The mistake she makes—which is a crucial one—is failing to notice that the neoliberal policies destroying their lives come packaged with the very framework for gender that she developed.

“We’d Be At Brunch Now…”

Now to be clear, many of those reactions are indeed what we can call right-wing and nationalist, but this points to the same sort of problem we saw in the United States during the candidacy of Donald Trump. His opponent, Hillary Clinton, was the paragon of neoliberalism, but of course she had another opponent too: Bernie Sanders.

Sanders represented something closer to the Marxist opposition to capital (though a watered-down and barely identifiable version of it). Sanders drew significant support from what Marxists and more traditional leftists saw as their primary base—lower and middle class workers—who were themselves reacting to the disastrous neoliberal policies of Obama and Clinton’s husband.

Trump and Sanders shared one defining trait that neither Hillary Clinton nor Joseph Biden possessed. Both men admitted there was something wrong with the way capital was working in the United States, despite having radically different ideas about what to do about it. Clinton and Biden both denied there was any problem with the system itself, instead focusing on social inequalities rather than economic exploitation.

Trump won in 2016 specifically because he actually spoke to the material conditions of American workers, despite having no real intention to do anything about those conditions. Clinton, on the other hand, spoke instead to the social and moral concerns of urban professionals while completely ignoring lower class conditions.

Though Trump is gone and American urban elites can all get back to brunch again, those material conditions affecting the mass of lower class workers (remember, the traditional “left” base) haven’t improved. What they are offered instead of better wages, reliable work, and access to affordable housing and health care are lessons on pronoun use and moral education on how to resolve their own invisible racism.

We will absolutely see a “reaction” to this in the United States, just as we are seeing reactions to this throughout the rest of the world. Judith Butler worries that “gender” has become a phantom enemy around which fascist movements are coalescing, yet completely misses the fact that gender is one of the bludgeons the neoliberal order is using now to dismiss the material concerns of the poor. People aren’t materially poor because of capitalism, they’re spiritually poor because they think that a person’s sex is linked to the physical reality of their body.

Again, Butler is correct that there is a “backlash all over the world” occurring. Also, she is not far from the truth in identifying “gender” as the symbol for the backlash. What she is absolutely wrong about, however, is the false dichotomy she creates between those who support these new conceptions of gender and those who are fascist. Another framework for understanding what is happening around gender is not only possible but crucial, especially if the left is ever going to mount a real opposition to capitalism.

In fact, this framework has already been pointed out by quite a few women you’re not allowed to read anymore because they are “fascist.”

Blind Assassins

Actually, looking at what happens to people who suggest a more nuanced view and more balanced framework regarding the question of sex and gender is crucial to understanding the problem with Judith Butler’s labeling of all who oppose her as fascist.

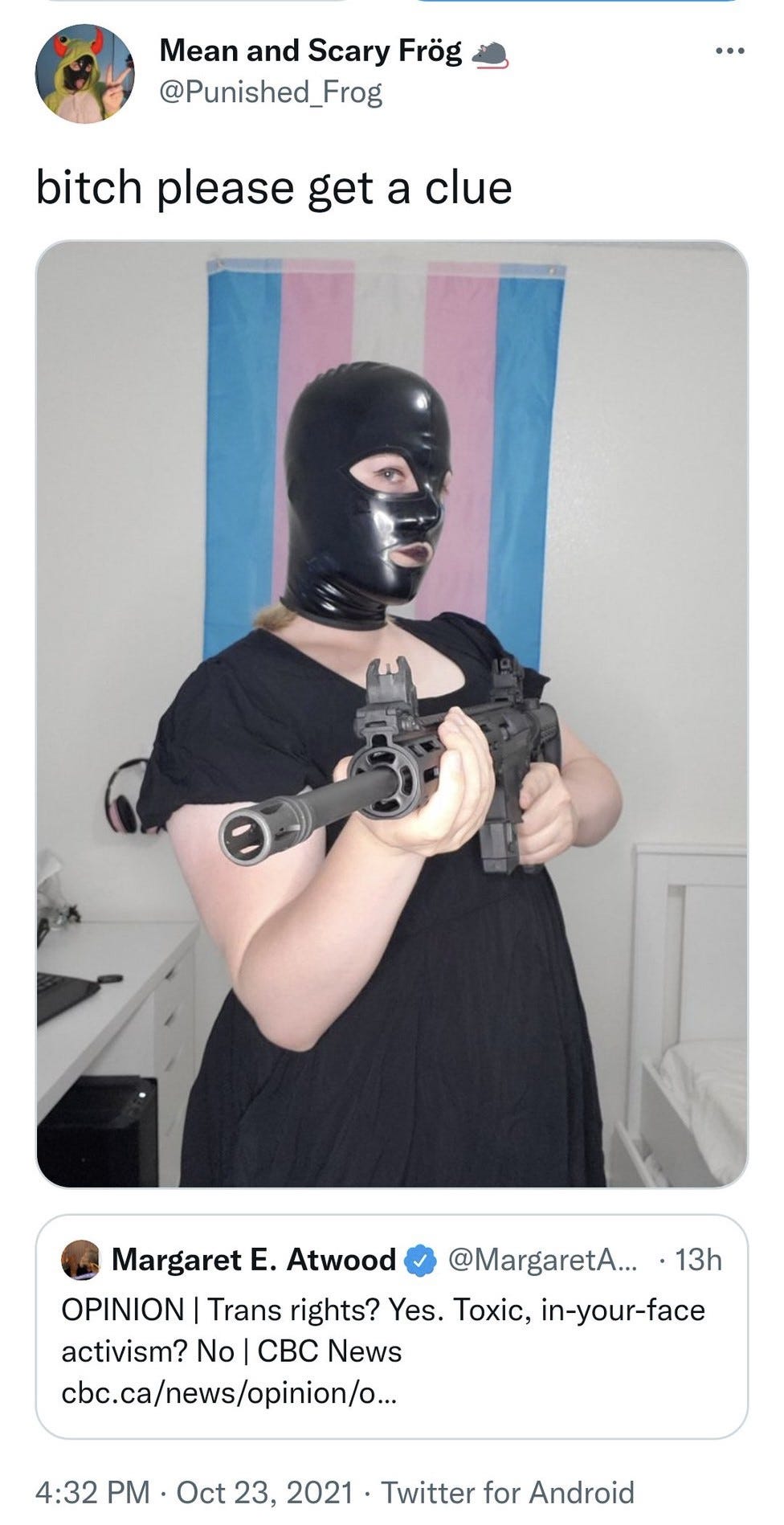

As you maybe know, Margaret Atwood has been the most recent woman author to get attacked for her understanding of the matter of women, attracting this sort of reaction to her “reactionary” views:

There’s much more of these if you need more evidence, archived in several places so you don’t have to log in to Twitter.

Now, generally, making rape and death threats is what we expect of fascists, not from people who claim to be fighting fascists. But then we used to think “mother” was a correct term for the person who birthed you, so maybe “fascist” doesn’t mean what we think it did, either.

What is more important here is the actual link Atwood posted. The writer of the article identifies as a transgender women and is critiquing the kinds of attacks by trans activists that Margaret Atwood is experiencing:

Any trans person, like myself, who doesn't agree with this type of activism and doesn't jump to the defamatory labelling of anyone who disagrees as a bigot or TERF (Trans-Exclusionary Radical Feminist) is usually called a "bootlicker." That's because, of course, women or feminists who campaign for women's rights are "fascists," from the point of view of these trans activists.

The author (Jessica Triff) then points out that there are real problems occurring with the matter of self declaration:

It's important to note that making legal sex change more accessible over the past 10 years has caused undeniable issues related to trans inclusion. A decade ago, you required therapy, approval letters from psych and medical professionals, hormonal therapy and gender reassignment surgeries. Today, in some jurisdictions, all that's required is a simple self declaration.

This gives legal access to women's intimate spaces, shelters and prisons to trans women who haven't necessarily gone through any medical transition or therapy.

There are instances where this has proven problematic. From certain self-declared women insisting female estheticians perform Brazilian waxes on male genitalia and threatening them with lawsuits or human rights complaints if they refuse. Or a criminal offender with a history of sexually predatory or violent behaviour demanding a transfer to a women's prison after self declaring as a woman. Women have been kicked out of domestic violence shelters for speaking to the media about sharing spaces with non-transitioned males who identify as women.

The author is hardly the only trans writer to point to such problems. Trans writers smeared as “truscum,” for instance, have been arguing for years that self-declaration of gender shouldn’t be enough to grant trans people immediate access to all woman-only spaces since it opens up the possibility of abuse. This is hardly a “fascist” position at all, but rather forms the foundation of a deeply compassionate framework that the left should adopt.

Such a framework argues for protections for trans people without undermining protections for anyone else, which should be the goal of any leftist project. What is happening now—thanks to Judith Butler—is the opposite. Supporting trans rights in the United States currently means telling an old woman to “suck my lady cock” or canceling a black comedian who supports such women, and this is what the United States is exporting to the rest of the world.

If anything, what Butler is arguing for is something that will ultimately do more harm to trans people throughout the world than anything Margaret Atwood could do. Stating that any resistance to “gender” is inherently fascist ensures that the kind of compassionate framework Jessica Triff and other trans writers are arguing for cannot exist on the left. The consequences of Butler’s framing result in such a view always being seen as fascist, and by extension also any trans people who hold such a view.

Again, I’d like to point out that Butler herself admits in that essay that the core problem is the precarity and societal disruption caused by neoliberalism (that is, capitalism). It’s right there in front of her the entire time, but instead of following that thread she repeatedly then concludes that anyone who resists her ideas about gender is a fascist. Thus, there are only two choices: the exploitation of the capitalists or authoritarian nationalism.

Other options still exist, just as other options have always existed for the modern deadlock of gender. If the left ever returns to a focus on the actual material conditions the capitalists create and exploit, we might have a chance to get there.

First of all, the title of your post is brilliant, I laughed for a few minutes before I read the article. Thank you for that.

Now onto the actual content - YES. I agree with Margaret Atwood too. Trans rights, yes. This kind of nonsense "activism" we're seeing right now, nope. And yes, even trans people who speak up and say "this is BS, stop making us look bad" to the "activists" get called TERFs. I don't belong anywhere anymore because, like I keep saying, I'm automatically unwelcome in conservative spaces as a trans guy (and a man-loving one at that), but I don't fit in LGBT spaces where you can't say "maybe we shouldn't be giving 12-year-olds hormones" without being called a TERF or questioning the sudden surge of "non-binary" teenagers without being called truscum and people harassing you and even doxing you, because "safe space" is totally about revealing personal info of a trans person to the public Internet.

I preferred Bernie over Hilary, and Bernie over Biden because I am poor (I don't mean in the way affluent whites think they're poor because they can't go to Tahiti this year, I mean "I shop at Wal-Mart and worry about rent" poor). Harris is VP explicitly because she's a black woman which is considered super-progressive even though she has a very non-progressive track record of sending non-violent offenders to prison (I am 100% opposed to prison sentences for non-violent crimes and think our prison system needs a massive reform, but that's not the point of this post), and if she runs for president in 2024 she's going to lose and we're going to end up with a second term of Trump or possibly even someone worse because only the woke are going to vote for her. Even people on the left like me are going to feel bad about voting for her. If there was a black female candidate who didn't suck, sure.

I also hate the way the word "fascist" is thrown around now these days and applied to "anyone who disagrees with me", which waters the word down.

And Judith Butler's writing style makes my head hurt. LOL.

Great post, thank you again for saying what needs to be said.

I think you spotted the hole in a lot of Butler-style thought. It's harder to see it when the language is obscure and dense, but easier to see it in her op-eds that are written in readable English. And it's not a thing that I think she (or thousands of grad students) are doing consciously - I think it might even be unconscious. It's that they basically set up a framework, and then discuss that framework in a way that allows for what I believe are called "floating signifiers" - concepts that are vague and also change throughout the essay. The floating signifier here is fascism. If you read it uncritically, Butler makes perfect sense. But if you read her critical theory critically, you start to see how much "fascism" floats around, sometimes meaning "an organized right-wing opposition to trans rights," and sometimes meaning "a reference to the idea that you can't make everybody equally progressive in terms of gender."