Neurodivergence? Or Alienation?

why “you might be autistic if…” videos and ADHD memes feel like they are describing us all so perfectly.

I rarely cite Freddie deBoer, though I occasionally read him. His writing output is quite prolific, and he often writes about the same topics that I do, and he’s also a leftist. On the other hand, he’s much more combative than I ever want to be about certain matters any longer, and more brash, neither of which are qualities I’d suspect he’d deny or even be embarrassed by.

I once wrote like that and didn’t like attracting the sort of people such writing attracted, people who often seemed just as mobbish as those on the right yet who pretend they weren’t being nasty because their politics were supposedly better.

Though it was obvious hyperbole, someone once referred to me during that time as a “social justice Alex Jones.” I doubt that person had actually read much of mine, and this was years before I even allowed myself to admit that the “left” as I imagined it in America back then was fueled by ressentiment and as obsessed with identity as their constructed enemies were.

Looking back at that criticism, while I still don’t think it was in any way accurate, I think the critic was at that time much more aware of the mobbishness of what’s often called the “woke” than I was. As irony would have it, that person is now quite devoted to the very politics he criticized me for and often attacks others for not being faithful enough to the righteous cause of identity.

There’s a larger problem I think that any writer who still considers themselves a leftist (such as myself, and also deBoer) has to struggle with when we look at the really bizarre things happening in America around identity. It derives from the conflict between utopian ideas of social progress or liberation and the Marxist materialist framework itself. Materialism asserts that the social is shaped and produced by the material conditions and reality of those composing that social. Utopian socialism, the specific political ideology which Marx and Engels were attempting to undermine with The Communist Manifesto, instead believes in the power of “social change” (education, moral training, enlightenment) to arrange society in a way that material conditions are better or more equal.

That unresolved conflict haunts all current leftist political movements now. Both American anarchism in its current form and left-liberal “progressivism” generally fit very well into the current of utopian socialism, while I, along with black Marxists such as Adolph Reed or Marxist feminists such as Silvia Federici align more with the materialist framework. From my reading of his work, deBoer is also generally in this second category.

A good way to understand how these two competing frameworks conflict is through the principle of alienation. Within a Marxist framework, alienation is the engine of most social conditions within modern society, and it is caused by the material conditions which capitalism must create and sustain in order to function. That starts with alienation from your labor and production: you do not get to decide what is done with the products of your work, nor do you even get to decide how you will work nor to what ends you will work. Instead, you must work for another to secure a wage in exchange for your labor. The person you worked for (the capitalist) then decides how to use your labor so she or he can best profit from it.

Though other Marxists have written on it, Silvia Federici best elaborated what else alienation from labor entails in her book, Caliban & The Witch. She showed that separating humans from their labor also required separating (or alienating) them from their bodies and from naturalistic conceptions of time (the work day becoming out-of-sync with seasonal and daily rhythms), and from land. We do not know ourselves as body any longer, nor do we relate to the land around us as a living, material thing, nor do we schedule our labor according to natural cycles of time but rather to standardized machine-time (clocks).

Alienation has many secondary effects that can be seen throughout social relations, which I will discuss in a bit. First, though, we need to look at how the current of utopian socialism sees the problem of alienation, and this is best seen in Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign speech to union members back in 2016, where she famously outlined what is now the dominant progressive (or woke, or utopian socialist) view on the relationship between social issues and capitalism:

“Not everything is about an economic theory, right?” Clinton said, kicking off a long, interactive riff with the crowd at a union hall this afternoon.

“If we broke up the big banks tomorrow — and I will if they deserve it, if they pose a systemic risk, I will — would that end racism?”

“No!” the audience yelled back.

Clinton continued to list scenarios, asking: “Would that end sexism? Would that end discrimination against the LGBT community? Would that make people feel more welcoming to immigrants overnight?”

Clinton of course didn’t just come up with this sort of analysis overnight, nor did she create it. For years before her campaign, “social justice” had slowly begun to supplant questions of economic justice not just in establishment liberal rhetoric but also American leftist political theory. Racism, sexism, anti-LGBT and anti-immigrant discrimination—rather than capitalism—became seen as the core problems of society, problems of a social nature that had social solutions.

The general thrust of utopian socialism is that more just and equitable societies can be created through better education and massive shifts in social understandings and narratives. If enough people understand that being racist is a bad thing, there will be no racism. Likewise, if enough people understand that homelessness and poverty and low wages are bad things, then we will have less homelessness, less poverty, and higher wages. Alienation—if it is even discussed at all—is also something that can be resolved through social change, especially by teaching people to embrace difference and their unique experiences as individuals within society.

There’s a shorter and perhaps easier way to understand the conflict between these two frameworks by looking at the differences between “oppression” and “exploitation.” The utopian socialist framework of progressive, left-liberal, American anarchist, and what we currently call Woke ideology uses the word oppression the same way Marxists use the word exploitation, but they mean very different things.

Take a situation where a woman is working the same job as a fellow employee at the same business but is being paid much less for it than he is. From the progressive (utopian socialist, etc) framework, that woman is being oppressed by misogyny. From a Marxist framework, she and her fellow employee are both being exploited by their capitalist boss, but their exploitation is obviously unequal (she is being exploited even more than her male co-worker is).

The Marxist framework (especially through Marxist feminists like Federici) has plenty to say as to why she is being exploited more, but we need to keep in mind that the end goal of Marxism isn’t to make sexual differences in exploitation go away, but rather to end exploitation for both of them. The utopian socialist framework, on the other hand, at best argues that the capitalist should be exploiting both equally so that women are not oppressed (through wage differences and unequal working conditions, etc) in these or any other situations.

You can probably see here why Clinton’s formulation is so maddening for Marxists, while those using a utopian socialist framework might not even have blinked an eye. In the Marxist framework, racism, sexism, anti-immigrant and anti-LGBT discrimination are all seen as methods of capitalist management (or what I often call “governing aesthetics”) and its arrangement of social relations. These are all social forms that have existed throughout multiple societies even before capitalism, but the specific arrangement of these social forms (or “oppressions”) within capitalism are merely very effective ways that capitalists manage the exploited class.

As long as a woman being paid less than a man blames the patriarchy for her different rate of exploitation, and as long as her male co-workers accept their higher wages as adequate pay-off for their exploitation—rather than all of them organizing against the boss for higher wages—then capitalism faces no threat from the labor it requires.

The utopian socialist framework instead speaks of oppression as if it were the core engine of capitalist inequality, with the unstated founding belief that it’s possible to have capitalism without inequality. That’s why so much of progressive politics is about representation and diversity. If there were more women, more black people, more queer or trans people, more immigrants, more disabled people, more of everyone except for “white cis-heterosexual abled-bodied men,” then we would eventually erase all inequality and oppression and capitalism would evolve into (utopian) socialism.

Conditions as Identity

The reason why I brought up Freddie deBoer at the beginning of this essay is because he recently wrote a bit of a rant regarding the social narrative of ADHD that I think is worth your attention (pun intended, maybe). In that essay he discusses and dismisses the idea that there is a set of emotional experiences that people with ADHD have that others do not.

I’ve been interested for a really long time in the modern (especially American) tendency to create an identity out of a condition, and particularly how that identity then goes on to define for the public what that condition actually is. Autism, for example, has shifted from a specific condition to a larger identity of neurodivergence: people whose cognition generally diverges from what is considered “normal” or more specifically “neurotypical” or “allistic” (non-autistic).

When last I used social media, it often felt as if my feed was at least half composed of people discussing their neurodivergent identity in much the same way that people discussed what it’s like to be gay, or black, or trans. Common to these discussions was what Pierre Bourdieu explained as institution and division. In other words, what it meant to be neurodivergent is defined in opposition to a proposed dominant category of neurotypical, just as being gay was defined in opposition to being heterosexual, or in the way that trans identity required the institution of “cis-ness” as its opposite.

There’s always been an underlying problem with instituting divisions this way, because you have to force an artificial homogeneity in each group. In other words, to create an identity category of homosexual, we have to assign certain traits to them that are exclusive to them and not found at all in heterosexuals. This falls apart quite quickly when we then examine each of those exclusive traits and find that they exist in both groups and are not actually homogeneous within either group.

Consider all the caricatured traits that supposedly constitutes gay identity. Enjoying shopping and clubbing, being stylish, engaging in unrestrained sexual relations, talking in high vocal registers, liking Madonna: none of these apply even slightly to me. Nor do any other traits with the exception of a functional one: I sexually desire people of the same sex as myself.

Even that defining trait falls apart when we consider that I don’t actually desire all people of the same sex as myself, but only a very tiny fraction of men with certain traits that are not limited to homosexual men or even to men. In all other ways, I’m probably much more like what is attributed to the “heterosexual” identity category; thus, for me the identity division itself has very little relevance.

“You Might Have ADHD If…”

I’ve never had an official diagnosis of autism or ADHD, but there was a while where I figured I probably “had” both. This is because the identity category of neurodivergent is quite broad and seems ever broadening. As you can see in the examples deBoer cites regarding “ADHD feelings,” the social definition of the condition can apply to anyone. Autism is quite similar: a year ago I watched a video by a popular autistic influencer and came away certain I must also be autistic. The thing is, I think anyone might have come to the same conclusion (want to check for yourself?) because, just as with the ADHD matter, the definitions were extremely broad and often contradictory.

This isn’t in the slightest to suggest there is no such thing as neurodivergence or ADHD or that people are making it all up, but rather to point to the larger role alienation seems to play in the theater of modern identity. Neurodivergent identity has become a way for many to explain their sense of alienation from modern society, their felt difference from others, and particularly a general feeling that society as it exists is not amenable to their own happiness or way of experiencing the world.

The “felt difference from others” is a crucial aspect that can be seen very easily through a quick social media search (any platform will do, really) of people discussing the difference between their own mental routines and those of a perceived or imagined other.

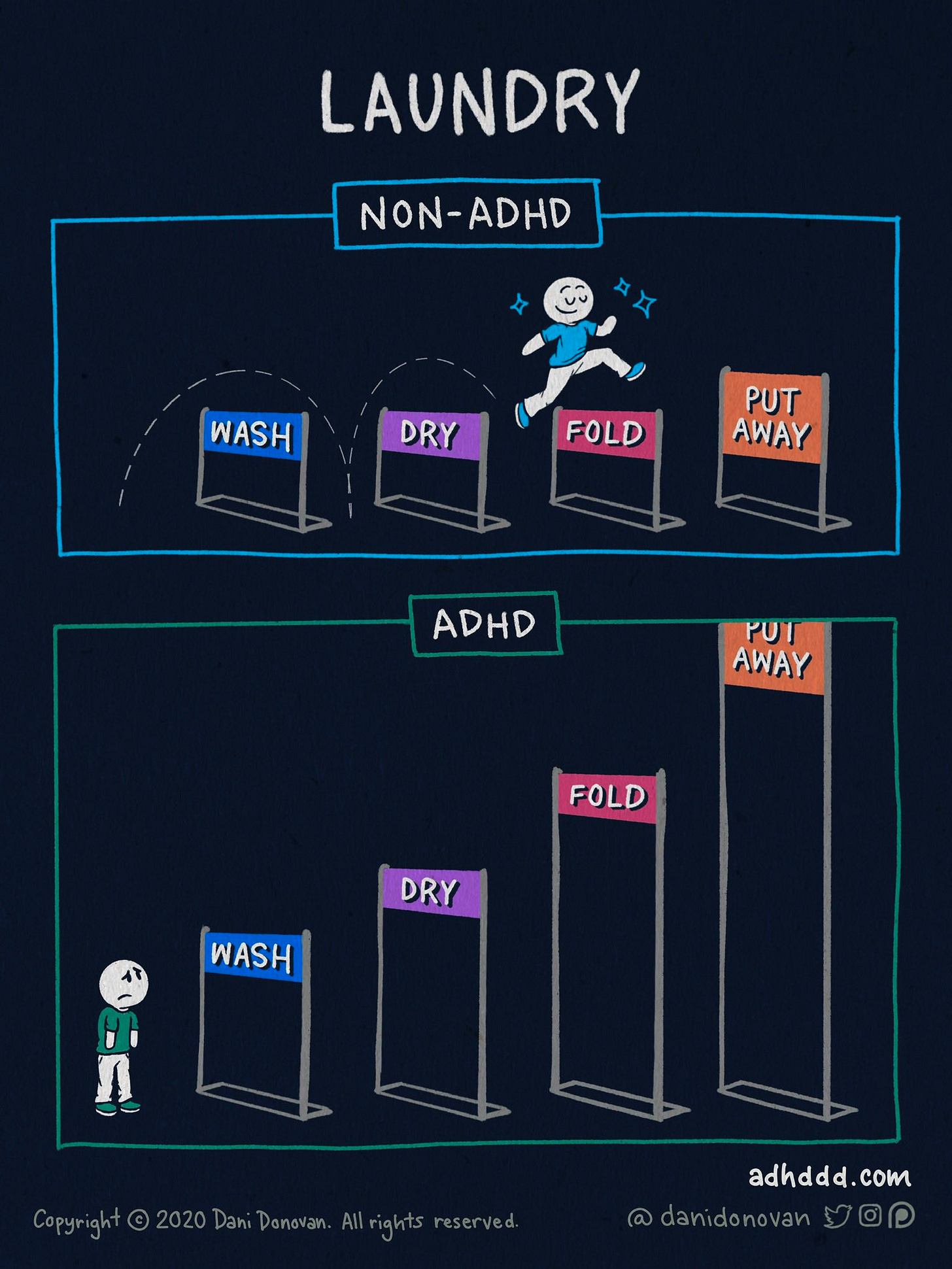

For instance, consider this image found at a website called “ADHD Comics” quite typical of the narrative:

Crucial to neurodivergence as an identity (rather than a condition) is this sense of comparison to what other people experience, the imagined other of neurotypicals. A “non-ADHD” person supposedly experiences a task as a straightforward series of steps, while a person with ADHD experiences each as an increasingly difficult hurdle. In other words, other people have an easier time of things, are essentially ‘privileged’ by their cognitive abilities, and therefore are better at doing everyday human things.

I don’t think it’s so simple as this, and I suspect most of you reading this don’t either. I’d hazard a guess that many of you have laundry you probably need to do, or really dislike some part of the process as I do. I handwash much of my clothing, especially my gym clothes and especially in the summer, and currently I’ve got a lot of socks hanging in the sun on our balcony that are certainly dry and could be put away.

There’s also more to wash, and I haven’t done that yet. Instead, I’m writing this essay. But not instead, but rather currently, because this is the part of the day I’ve set aside for writing rather than laundry. Later, I’ll gather the dry clothes and put more clothes in a bucket to wash before going downstairs to help my husband on our week-long project: building a new walkway, pond, and garden plot in our backyard.

In fact, my day is already quite full of things to do, and I have many other things to do as well that I know won’t get done today, and it’s quite possible I’ll fret a bit about them not being done—if I let myself fret about them.

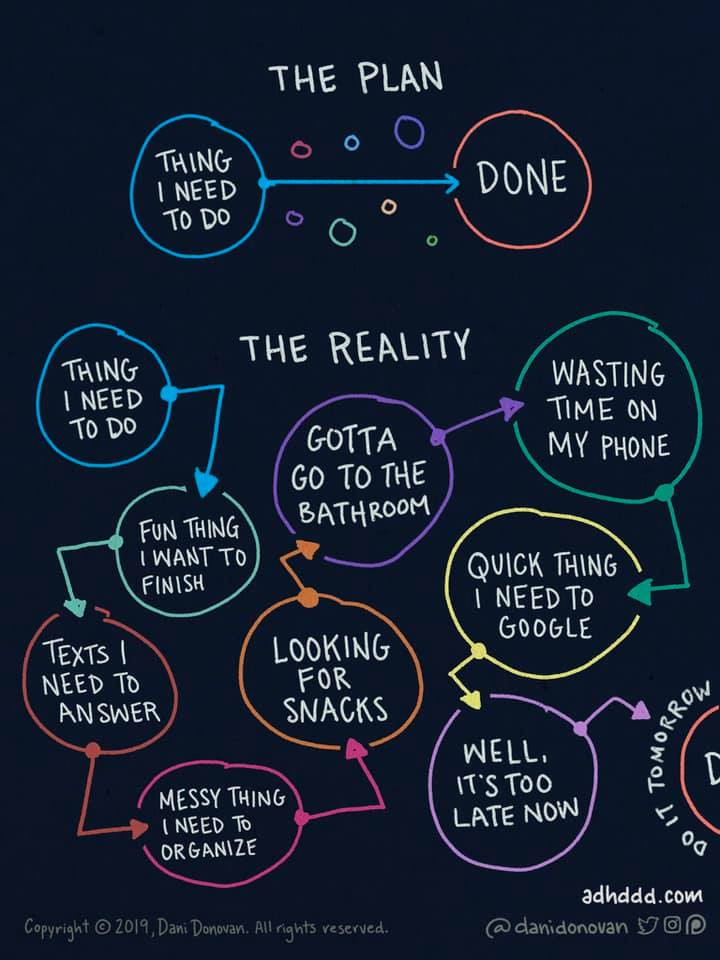

That leads to another aspect of neurodivergent identity, the belief that there is actually a straightforward and simple way to do anything without complications or interruptions. In this conception, neurotypical people supposedly are able to focus on one task without interruption or distraction, while the neurodivergent are not:

It’s worth noting in this graphic how many of the proposed interruptions that a ADHD person experiences relate to digital technology (texts, googling, wasting time on phone). This is a very common theme on social media descriptions of neurodivergence, especially in the examples deBoer cited of ‘open tabs’ on internet browsers. Another comic on the site shows this even more clearly:

I mentioned earlier that watching videos about autism left me with the feeling that I was likely autistic. Reading descriptions about ADHD has the same result, especially the above graphic. Likely you are feeling the same. But if we step out of the idea of neurodivergence and especially the identity framework created around it, we can start to see how alienation might point to something much, much bigger.

Why Can’t You Just Focus?

I suspect the vast majority of people experience a sense of time distortion (or better said, time theft) when playing video games, watching YouTube videos, or checking their phone. It’s probably also safe to say that most people encounter all kinds of distractions on their way towards completing a task, or experience the very last step in a multi-step task (putting away laundry, for example) as feeling more daunting than all the previous steps. As deBoer puts it rather directly, “I’m afraid I have grim news for all of these people hoping to wring an entire personality out of their various cognitive disorders: you’re just like everybody else. We all are.”

However, I think deBoer’s “toughen up, buttercup” response unfortunately misses a larger point.

The above is a list of the top viewed websites worldwide at the end of November, 2021. Of those ten, three are search engine portals (Google, Yahoo, Yandex) which are usually the default homepage of browsers. Two more (Wikipedia and Amazon) function as global information and shopping databases, leaving the remaining five.

Four of those remaining five are social media platforms (I count YouTube as social media) engineered specifically to be addictive, while the final one, Pornhub, is the largest purveyor of pornographic videos (which are highly addictive even without being engineered to be) in the world.

Our interactions with internet technology are ultimately alienating, and it’s meant to be that way. Going to Wikipedia to learn something rather than a library or a knowledgeable friend, masturbating to pornography rather than using imagination or actually having sex, and “being social” over social media rather than hanging out with flesh-and-blood humans, shopping for products on a screen rather than going to weekly markets or shops in town centers: these are all equally effects and engines of human alienation from ourselves, each other, and from our bodies.

Of course we have trouble focusing. Of course we have difficulties expressing ourselves to others and understanding the nuance of their emotions. Of course we have the sense that simple life tasks and complex relationships are somehow easier for others than they are for ourselves. Of course it feels like our mental landscape is cluttered and chaotic. Of course we feel like our time gets stolen doing certain things while other more urgent tasks seem to stretch on interminably.

We’re living in technologically, economically, and socially alienating societies and accept this all as a default state. Those who seem to adapt better to that alienation must be “normal” or “neurotypical,” while the rest of us are the broken ones who re-narrate our alienation as something unique.

The Time of Work

I took a break while writing this, and during that break I brought in the aforementioned dried laundry, so let’s return to the matter of tasks, work, and alienation. We think now of tasks as something that needs to be done, something that must be scheduled in to our life, and especially as something that represents an interruption to life itself—but this is exactly what alienation from labor looks like

Before the rise of industrial production and its dominance of the world, and particularly before the widespread introduction of the wage, we didn’t measure work by time. Instead, it was time which was measured by work, measured in the sense that music has measure. The time of milking cows, the time of harvest, the time of planting, the time of hunting, the time of mending: the task had its own time, and this was not a time rung out by clocks.

I’ve mentioned several times previously, but where I am living now is on a larger area of land where there was once a laundry house. That’s where the women did their laundry, and they did it together. Harvesting, planting, and most other agricultural work were also communal or group activities, as was hunting, logging, brewing, butchering, baking, and almost every other kind of labor within non-industrial society.

We rarely worked alone even when the work we did only needed one person. The mother or grandmother mending clothes wasn’t by herself in a room struggling not to look at her phone, but rather sitting in the main room of a house with others doing other work or nothing at all. Now, we’re all struggling to focus on the most basic tasks from which technology supposedly liberated us decades ago, and much of that is because we’re doing it all alone.

We also stopped understanding the way work has its own time. I’ll have all my laundry washed, dried, and put away tomorrow. Not today, because I can only wash so much in a bucket and have space only for some clothes to dry, but also I don’t need to wash everything at once anyway. If it were autumn and raining, I’d use a machine instead, and I’d wash everything at once rather than over several days as handwashing demands. All this is to say that the work itself sets the measure, and also the time of the year, the conditions of my life and also the conditions of the land.

Another aspect of our alienation from our labor is also that we’ve lost the cultural understanding of what must be done now and what we can sort according to our own rhythms. A harvest cannot be rushed nor procrastinated: wait too long and you’ll lose everything, try to do it earlier and you’ll reap little. It is the same with sowing and many other crucial aspects of farming, but not for every task. That fence that needs mending might have a little more time before the animals break through it, the tool that broke might not need to be fixed until it will definitely be needed again, the milled grain doesn’t all need to be turned into bread immediately and will anyway be wasted if you try.

The ability to understand what was needed now and what could wait was both a culturally and religiously ritualized knowledge, and was taught from parent to child and from myth and festival to people. We have nothing of the sort now because alienation from labor also required alienation from community and alienation from embodied forms of wisdom and teaching.

That alienation has left us moderns as shambling wrecks of humans, desperately trying to force ourselves to become more focused in a world of technology constantly trying to steal our focus. We berate ourselves for being undisciplined with our time and impulses in a hyper-mediated economy which needs us to overspend and impulse buy in order to keep profits growing. And we then look for identity formations and pop-diagnoses to explain for us why we’re not doing any of this very well while we imagine others are.

Most aren’t, though. Those who are handling this all much better are never going to be the people we’ll encounter through social media, because they wisely realized they actually can’t accomplish what they desire and need to do while spending hours on Twitter or Facebook. The perfect and balanced life of the Instagram influencer is an illusion: if it were perfect and balanced, they wouldn’t need to keep posting images to prove that it is. The activist tweeting ten times a day about fighting injustice isn’t fighting anything at all except for his social media addiction, and he’s losing.

That sounds like a reproach, and perhaps it is, but what’s crucial to understand is something we’re taught to forget: human attention is limited, as is human labor, as is everything about humans. There is only so much time in a day, and there is only so much you can do in that day. Re-ordering priorities, setting self-imposed limits on technological interactions, restraining impulses and postponing immediate pleasure is really fucking difficult, but it’s also the only way to cultivate a life where pleasure and desire have their own time and own measures, too.

We don’t live in societies which help with such limits or even acknowledge limits as a good thing. Instead, those who admit their attention is constantly interrupted and stolen, or who confess to feeling unable to communicate or even complete simple tasks are seen as (neuro)divergent, that there is something wrong with their brains. It’s understandable such people would then seek to transform their diagnoses into something more honorable, an identity that makes them special or at least gives them a sense of dignity.

Rather than dismissing their experiences or telling them they’re no different from anyone else, what if we instead saw in their accounts honest reporting of how alienating modern industrial society actually is? In other words, maybe they’re not just telling us about their experiences, but also about our own. Perhaps that’s why “you might be autistic if…” videos or ADHD memes can so easily feel like they are describing us so perfectly.

Maybe they are.

Maybe none of us are actually evolved for this kind of world, maybe none of us have the capacity to focus our attention on things we need to do when everything else is demanding that attention as well. Maybe internet technology is “rewiring” the way we think, maybe social media is harming not just our friendships and relationships but also our ability to communicate as humans-as-bodies, maybe all the devices that constantly interrupt our thoughts are actually shaping our way of thinking.

Maybe we’re all neurodivergent, all “on the spectrum,” all a bit schizophrenic now. And maybe that’s what is becoming the (neuro)typical, the default state of human cognition within capitalism.

And maybe we can decide we don’t want that anymore.

I have ADHD and I find more comfort in thinking about how the desocialized nature of work today is bad for everyone than I find comfort in thinking about the idea of how other people have an easier time doing things.

Letting your neurological symptoms stand in for alienation can be comforting... I messed with that a little bit but found diminishing returns.

I'm 37 and I wonder if, had I been diagnosed just a bit younger, with more of an idea of a "whole future ahead of me," and more proximity to my youthful embarassments, I would have gotten more into the pasttime of imagining that things are easier for other people. At my age and stage in life, I don't think "Ah, now that I know this about myself, it will all really make sense!"

Sometimes, I'll leave the house without a wristwatch. Before I knew I had ADHD, I did that all the time and thought "Yeah that's fine I'll just use my phone." Having the diagnosis helps me to make a different decision. Knowing that I have ADHD, I just take more seriously the idea that I'll function better with a piece of jewelry that tells the time and doesn't also browse social media or receive text messages.

Like the wristwatch, all of my coping strategies are ordinary organizational things that I just take more seriously now because of the diagnosis. When I first received the diagnosis, I was more into "neurodiversity" content and I think I became a bit depressed while consuming it. I started wondering if I was missing something... it seemed that everyone else could get validation and pride from this condition but I couldn't.

I wish I'd somehow been able to foresee that the little lifestyle changes which I always knew were important for ADHD were basically all there is that's worth doing about it. Any hope I had of reorienting my worldview and experiencing more of a sense of harmony because I now had a label for my brain... I thought that would happen and then it just didn't.

I agree with you that Freddie's pep talk kind of masks the greater reality of alienation. One thing that's tough to grapple with these days is, well, how much everything is alienation.

I think I'm slowly coming to terms with something that I suspect other "bernie bros" like me are coming to terms with: that if I truly believe that idpol nonsense is a mask of material problems, I have to accept that people who believe in idpol nonsense will respond to criticism emotionally, because it feels like criticism of the real problems that are under the silliness.

I'd never insult my sjw-style friends' dumb ideas, and it's not because "they'll yell at me," it's because I know that their idpol ideas are emotional standins for material problems. If I criticize their ideas without keeping that in mind - that if I poke a goofy idea, a real problem will feel pain - I'm just being a dick.

Your description of a home from 100 years ago was extremely vivid and got me thinking more deeply about something I've thought about many times before.

For a lot of people, having a subculture provides more hope than anything else. That's unfortuante because I think that that is unsustainable. I believe that just like Marx's "tendency of the rate of profit to decline," there's a "tendency of the psychological value you get from a subculture to decline."

And by subculture, I mean something more specific, which is the sense of elation you get when you and another person say to each other "You have that hyperspecific behavior? Oh my god so do I, we're part of something!" I think it's inevitable that one day you'll no longer feel that elation but will still feel like you must be part of it. I think that's how subcultures always decline.

Nice synchronicity to see this in my inbox on the day I deactivated my twitter account!

I have come across plenty of ADHD content on Instagram and TikTok which I found very relatable - but finding it relatable seemed to have more to do with the effect that spending time on Instagram and TikTok had on my mental state than with anything inherent about the way I exist in the world. It's notable that a lot of the videos either have a peppy 'why your neurodivergence is a superpower' tone or adopt a 'you probably didn't realise you were neurodivergent' angle - both of which seem to lend themselves more to identity-building than to practical help or greater understanding.

Your work on ressentiment has been so helpful for thinking with the ways in which identities tend to be expressed online in opposition to an imagined 'other' - and the effect this has on the way we relate to one another. Our needs and strengths and joys and struggles are valid in their own right and on their own terms, and it can be easy to lose sight of that, in all the convoluted steps we have to take to get them recognised and met in our current way of living. For some people, diagnoses can be really helpful in understanding and expressing their needs, in a world which views any difficulty in adapting to machine time as some kind of deviation from the norm. But diagnoses are a double-edged sword, and identity can trap us just as easily as it can help us.