I took a train to Trier on Tuesday, to lose myself for a few hours among statues of gods.

I hadn’t planned to do this. In fact, I’d meant to go to Paris for an event, to bike early from my village to a nearby train station, then take the train from there to Luxembourg city, then to Metz, then to Paris.

Unfortunately, that all fell through on account of strikes in France, a grève générale.

France is one of the few nations in the world that still has unions with political power and popular support. They go on strike quite often, and though their unions are very often at political odds with each other they regardless show a kind of practical solidarity unseen elsewhere in the world. Also, both their leaders and their members have a much better sense of the long-term effects of government decisions and international events on the wages and working conditions in France than unions elsewhere.

This strike had quite a lot to do with the United States, and Russia, and their proxy war in Ukraine. It was also about the larger neo-liberal trend towards austerity and the globalization of capital. I’ll get to all that in a moment, but the gods are more important.

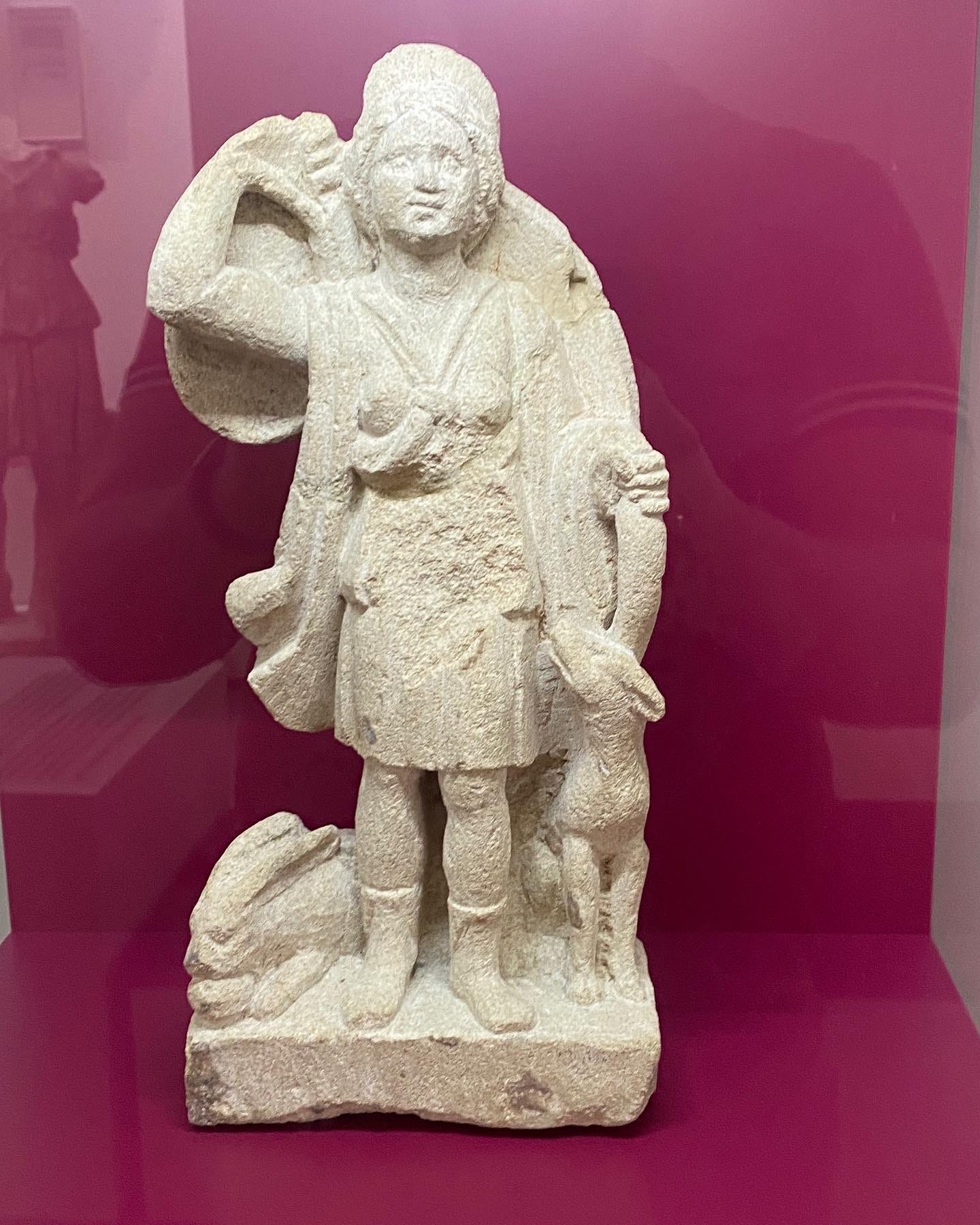

That’s Diana, or one sort of Diana. Things get a bit complicated when you speak of old gods and try to identify them, because the Romans and then later the Christians and especially the neopagans (who are just Christians with funny clothes) tend to universalize everything.

Diana is a huntress goddess, though it’s just as true to say “Dianas are huntress goddesses.” There are quite a lot of Dianas and quite a lot of huntress goddesses. This Diana, found in the Ardennes where the Treveri Celts lived, could quite possibly also have been an Arduinna or a Freyja, depending on who you asked and where they were from.

My favorite part of Dianas are the boots. As with Christian iconography where a saint is identified by something they are holding or wearing (Catherine’s Wheel, Donatus’s lightning bolts, Barbara’s Tower), you know it’s a Diana by the boots. Often she’s got a bow, a deer, and a dog, but the boots are what always draw my attention.

That early propagandist, Gregory of Tours, tells us that a man named Wulflaich sat upon a pillar outside the city of Trier because the locals still worshiped Diana instead of the new one-god. The fact that he let ice form upon his beard during the winter while he perched there supposedly convinced the locals to tear down Diana’s statue. Of course Gregory forgot to mention all the axes and swords of the newly-converted Frankish kings who ordered those statues torn down.

But sure, it was a dude sitting on a wooden pole.

It’s not just the Christians who tell such tales. In the part of the museum introducing the Roman occupation of the Treveri, a sign explains how the Celts “enthusiastically” embraced Roman beliefs and cultures, “aided and inspired by” locals who became wealthy through their deals made with the conquerors. Of course there was also Caesar’s recent slaughter of the Gauls at nearby Alesia, his crushing of other Celtic resistances, and the threat of Frankish invasion if they didn’t accept Roman occupation.

But sure, dude. It was their “enthusiasm.”

Two of my trains on Tuesday were cancelled, while a third was still running. To get to Paris I would need to get to Metz first, but the train to there and an earlier back-up train were both caught up in the strike, “supprimé” (deleted) as the timetable declared. Having already committed to taking the day off work, and really needing to go somewhere, I then decided I’d go to Germany to see old gods.

For a strike to be “general” rather than specific, it needs to involve the workers of more than one industry going on strike together. For instance, if retail workers walk out of their jobs, and then electricians walk out to support them, and then nurses go on strike, then it becomes general. In other words, it’s a collective strike that shuts down not just one part of the economy but rather several parts and ideally all of it.

There hasn’t been a general strike in Luxembourg since 1942 or in Germany since 1920. Belgium’s last general strike was in 1960, and the last real general strike in the United Kingdom was 1926. In the United States, several events have been named a general strike, but the most recent one which could actually qualify as such occurred in 1934, but more accurately it was probably 1919.

On the other hand, the French declare such strikes very, very often. The most well-known—and indeed the largest in Europe—was the May 1968 strike. That one pulled in almost a quarter of the entire French population, grinding the economy to a halt and forcing the government to dissolve the national assembly and call for new elections. It also set off a wave of other actions across the world, as well as a co-ordinated effort to undermine organized labor by governments in Europe, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

The strikes on Tuesday weren’t nearly so widespread. About half of all trains stopped running, schools shut down and many hospitals had to reduce their services, but very little else happened. Despite their limited nature, that strike is part of a much larger reaction in France to increasing cost-of-living, stagnant wages, and especially the really high price of energy and petrol.

What’s happening in France is a direct result of what’s happening in Ukraine, and also a direct result of capitalist re-organization of politics and society. Russia’s war against Ukraine led to European and US sanctions against Russian fuel sales, which then led to an increase of the overall prices of natural gas, coal, and other energy sources. This means higher prices for consumers, but also even higher profits for energy companies. TotalEnergies and ExxonMobil (called “Esso” in France), both of which had already posted record profits for 2021, are likely to almost double those figures in 2022.

Besides the rising cost of petrol at gas stations, home energy prices in France (as throughout Europe) are terrifyingly high. Neither of these increases are accounted for in inflation rates, so the 6% inflation in France doesn’t include these costs. This means that, besides finding that your money buys less and less each month, more of your money also goes towards getting to work and lighting and heating your home.

Last Sunday, there were large protests in Paris against energy and other price increases, while Germany has seen many such protests in the last six weeks. Similar protests have also happened in Belgium, Austria, Italy, and Spain, and it hasn’t really started to get cold in Europe yet.

In France, workers at the oil refineries and nuclear energy power plants were already on strike. The wider event on Tuesday was called in response to the government forcing some of those workers back on the job. Especially maddening is how Emmanual Macron has attempted to play the French public off against the workers, blaming the unions for the price increases and fuel shortages rather than his support for Russian sanctions and his austerity policies.

For their part, TotalEnergies also is doing the same thing, offering a small rebate to poorer households on their energy bills and a ridiculous gimmick at some of their fuel stations. For every fifty liters purchased, you get 5 euro back. In other words, “buy 50, get two and a half free.”

This is Epona, the Celtic goddess of horses. For the Romans who conquered those Celts, she became a goddess of horsemen.

My German isn’t very good. Unfortunately, neither was the German spoken by the Syrian immigrants working as security at the museum, so I ended up in the wrong area full of imperial relics and Christian statues rather than clay burial pots and gods. I didn’t want to be in the Roman exhibit. Rome is how everything went to shit, how all the gods got squished up into singular gods and then just one god. Rome is how a relatively peaceful monotheist cult became a slaughtering ideology which later birthed capitalism and neoliberalism. And Rome is how Epona became a goddess of horsemen, rather than horses.

Fortunately, I found my way by doing precisely the opposite of what the staff insisted I do and could then revel quietly in what the world was like before Rome.

Ancient history museums always seem to follow the same pattern of marking linear time. They start with arrow heads and bone fragments, then to early clay burial urns. Then, suddenly there’s bronze and the burial urns and axe heads are metal instead of earth or stone. Next are the cauldrons and the jewelry, and then the glass fragments, and then all of a sudden the gods.

According to this narrative, the gods arrived late because the statues came late. The problem is that there’s a funny shaped female figure that keeps showing up long before, the so-called “Venuses” (the most famous one was found in Willendorf.) Even older than its 25 thousand years of age is the oldest statue thus far found, the 35,000 year old "Löwenmensch" (lion man) carved from ivory and displayed in Ulm, Germany.

We humans have been making images of beings besides ourselves for a very, very long time, and we’ve been treating those images as sacred things. We cannot say they were all gods, but we also cannot say they were not. The problem is that our idea of what’s a god is bound up and limited by Roman religion and its monotheist successor. Except for a few gods (like Epona and Isis) who filled a need they hadn’t previously met, Romans renamed the gods of others as their own gods.

Like a corporate coffee franchise buying up local competitors and changing the signs on the door, Rome kept the structure but redirected the value towards new shareholders. Christianity continued this, which is why so many churches and shrines are on the sites of previous pagan temples. It’s not as dire and complete a transition as an American reader might think, however: anyone can go venerate Thor at a shrine to St. Donatus just up the hill from where I live, or Rosmerta, Arduinna, and Freyja at quite a few Catholic shrines at trees and springs nearby.

What actually changed was the way the world was ordered in our minds, and especially who and what our personal venerations and beliefs should serve. Again the matter of Epona is relevant: a goddess of horses become a goddess of horse-riders, the horse existing first for-itself and then later seen as existing for those who use it. The Romans used horses and chariots pulled by horses to conquer, and thus Epona and her horses were made to serve empire.

I’d have to be a self-centered narcissist to be against the strikes in France, and to be completely blind not to see the larger logic behind Macron’s neoliberal austerity policies. At the same time, I’ve been quite critical of certain parts of the French left, parts which mirror the impotence of the entire American left.

The basic principle of a strike is really simple yet utterly lost to some. In a strike, you withdraw your labor from the capitalist class, and without your labor they cannot profit from production. In order to go on strike, though, you need to be a worker. That means if you’d rather just live off state socialist programs, as many anarchist-aligned French radicals do or as the “anti-work” utopian socialists in the United States hope to do, then you have no labor to withdraw.

At the same time, you become more reliant on a stable and powerful state to fund and administer the social programs that enable you to not work. For such people, a threat to the state ultimately threatens their ability to survive, and thus the government can constantly play them off workers by offering a choice between concessions to workers (salary increases, retirement benefits, etc) or social programs and symbolic “rights.”

This has been the neoliberal scythe hanging over the American working class for decades now. The Democratic Party has gotten quite good at this game, freely offering identity recognition and limited social reforms to minority groups while keeping wages stagnant and weakening the power of organized labor. European governments are late to this trick, and the working classes here are much more difficult to dominate so easily, yet it’s happening regardless.

One of the most common statements I’ve heard from people here, from both the left and the right, is that neoliberals are attempting to turn Europe into the United States. This is the core of the complaint against “le wokisme” on the far right in France, but also the far left’s resistance to social justice identity politics as well. Both see a creeping cultural imperialism transforming European societies into something even more market-driven and more alienating. They’re being offered more consumer products and more gender identities in exchange for fewer jobs, older retirement ages, and less authentic social relations.

Everything is again transforming here, just as it has many, many times before and as it just recently did in the United States. Perhaps it’s not actually that capitalism profanes the sacred, but rather re-appropriates it into its religion.

Not very long ago, we would never have used the word “friend” for someone on social media, and a “follower” was someone devoted to an idea or a belief, not a stranger looking at your selfie on the internet. A decade ago being “connected” meant being part of an really-existing community, not being on your phone engaging virtual placebos for community.

It’s those cultural transitions—and countless others—which are now allowing this current crisis to continue in Europe and preventing any real challenge to those engineering it.

In every ancient history museum I’ve been in, there’s always a predictable moment where either the lighting changes or some other subtle effect is employed to remind you that you’re in Christian times. In the museum in Trier, for example, the walls all suddenly become dark and the statues are lit by spotlights rather than overhead lamps.

This shift is actually rather helpful, especially if the exhibition moves directly from statues of gods to statues of virgins, saints, and Jesus. You need this reminder, because the style of sculptures doesn’t really change significantly. In fact, if you weren’t aware a new religion had just arisen, you could easily mistake the Christian statues for pagan ones. The Frankish St. Catherine I saw (pictured above), for example, looked hardly different from the statues of Rosmerta I had just passed.

Cultural shifts and cosmological changes can seem sudden and total when we look at them through the lens of literature and history, but when you’re walking past the physical relics of that transition you notice it’s not nearly so complete. A new religion replaced the old, yet even 1500 years later priests were still trying to root out pagan continuations from their faithful. The smashing of churches, altars, shrines, healing springs and even megaliths during the Reformation in Europe, for example, was aimed at cleansing Christianity of its idolatrous pagan holdouts.

We’ve been engaging in “idolatry” for at least 30,000 years. When you look at the actual material lives of a people, rather than the ideological overlays, you start to suspect we don’t really change much at all. Something about us persists, and something about us keeps going back to the same forms and same ways of being regardless of who is in control and what we are told we should believe. The material always wins out, though its impending victory no doubt looks like desolation and terror for those who’d prefer not to remember we are human.

The European energy crisis now is one such place. For capitalism to exist, it needs absurd amounts of energy to fuel every part of its production chain. A city such as Paris can only exist because of expansive agricultural distribution networks which feed its crowded apartment buildings, and that requires energy. Not just Paris, though, but every city, and every town, and now every village. We’ve all been pulled into an ordering of the world in which everything depends upon cheap and easily gotten energy.

Now that’s all in crisis, and who we blame for this crisis depends entirely on our political religion.

Just as Gregory of Tours forgot to mention the bloody slaughter behind the “miraculous” conversions of the Treveri and the Franks to Christianity, there’s always something missing in the official narratives of modern cosmological shifts now. We do not convert to the modern religion of global capital of our own free will, but rather find ourselves born into, coerced into, and especially threatened into it.

We need all this energy because we no longer have the ability not to need it. Rising costs of oil and natural gas threaten not just lifestyles but lives themselves: winter approaches, and humans don’t survive in cold conditions without some sort of heat. Entire cities would starve because they cannot feed themselves without globalized agricultural production. All other production and the economies they create would collapse in days because the vast majority of proletariat cannot even get to work without petrol or electric energy.

Russia dammed up the flows. Not just Russia, but also Ukraine’s insistence not to negotiate. Not just Russia and Ukraine, but also Europe’s rush to destabilize its own societies in order to destabilize Russia. Not just Russia, Ukraine, and Europe, but also the United States’ intention to fight Russia to the very last Ukrainian. And not just all of them, but also our endless expansion, ravenous appetites, and utter refusal to live like our ancestors did.

Even the strikes in France feed into all this. There was a 20 kilometer traffic jam of French workers driving into Luxembourg the morning I was supposed to go to Paris, 20 kilometers of unmoving cars using extra petrol that fuels the profits of the very companies the strikes were meant to harm.

The moment political power becomes significant enough to universalize cultural forms it rises to the level of religion. All the huntress goddesses became Dianas, and then there were no more huntress goddesses at all but just a one-god. Individual distinctions become suppressed, individuals begin to not just think alike but to think in the same frames and the same forms. We tell ourselves we no longer believe in a universal god, but we regardless cannot escape thinking in the way one thinks when one thinks there is only one god.

Everything feeds back into that universality, that singular way of living, that compressed and imploding truth. There is no escape from the one way, which is now the way of oil, of capital, of production and consumption directed always upwards, transcending all our differences and desires to serve an order of meaning we cannot shape, control, or resist.

Yet try as I might, and honestly I’ve tried, I cannot ever truly make myself believe there is no escape from this.

That’s why I went to see the old gods, or more specifically to see what humans made for the old gods. Art is excess, the “accursed share” we consign to a space fully outside utility, purpose, and even meaning. Art for the gods in particular is excessive, created for things unseen, sacrifice to inspire sacrifice. Unlike the saints and virgins and saviors crafted in the service of an imperial religion, even the “imperial” gods of Rome ultimately undermined the foundation of Empire and were the first to be destroyed by the Christian emperors.

Diana and all her divine huntress sisters lasted much longer. Songs still invoked her lantern the moon in the 13th century, and into the 15th century, bishops continued to write their complaints about the faithful shouting her name at full moons and secretly visiting forest shrines.

It shouldn’t be surprising that she persisted, but I don’t think it’s for the reasons the neopagans believe or the Christians feared. There was no widespread witch cult in Europe, but there has always been a part of people here that escapes full assimilation into singular political religion. That resistant part is the wild part, the “forest” part of bare life, where what you need can be gotten in abundance among the trees rather than the city streets.

Thus it makes easy sense that a divine huntress who rules over, who understands, and who guides humans into those wilds would be seen as such a threat to the civilized order and such a refuge for those who resist its order of meaning.

I think there's a hole in this. I've been trying to put my finger on it, acknowledging my own biases as I do.

Maybe what you're doing here is constructing your own kind of political religion. I think the problem is in the notion that, for example, 'All the huntress goddesses became Dianas, and then there were no more huntress goddesses at all but just a one-god.'

That's a description of the creation of a monoculture from varying and diverse cultures. But it doesn't say anything about the reality at its heart - or otherwise. It sounds like a political claim from someone who wants to condemn empire and capitalism. I am happy to join you in that condemnation. But it doesn't seem to me to be the case that varying gods were channeled into a 'mono-God' for political reasons. It seems to me that people stopped believing in the varied gods and started believing in the creator god instead.

I'm not suggesting force and politics were not often involved. Of course. But I think the claim is not just political. I also think it's important to see that the 'gods' of the pagans and the 'God' of the Christians (and other 'monotheists') are not comparable, despite the common use of the confusing word. It's the difference between creator and created. The Christian God is 'everywhere present and fills all things' - created reality itself and is within it, alive amongst it, and total. That's a metaphysical claim. It's a huge metaphsyical shift that is happening as the world moves from 'pagan' to monotheist. It's by no means just a crude political manouevre. Some new sense is opening up. And the ultimate question is not political. Does 'the one' exist, and if so what we can we know about him/it? And how can we reforge our borken connection? That's a move from created to creator.

It's also worth saying that medieval Christendom, with its emphasis on the sinful nature of usury, held off the development of capitalism for many centuries, as did the eastern Orthodox world. It was the reformation which opened up the space for radical individualism. Something else we can blame the Americans for ;-)

I'm not sure I've explained myself very well. I'm not trying to be defensive, but as someone who has been both pagan and Christian, I can see a radically different worldview at the heart of things, and a different experience too, I think.

Hmmm, it’s difficult to parse the inner/outer journey between these two roads taken. I resonate with Rhys’ discussion of Dianna and her persistence thru the centuries as a force for connection and worship of the wild; also for the portrayal of the imperial domination of Rome to move the old god of the horse to horsemen. An example of the usurpation and co-opting paradigm that infinitely cloaks and obfuscates our truer natures as part and of the world. AND we, the totality of WE, are the Word made manifest. Is that not the paradox? Why must there be an either/or?

It is a beautiful essay here and one I relish from Rhys for his deep and discerning analysis of the historical origins. Particularly the contemporary cultural and societal citizenry of France who still express a collective sense of power in action that the rest of the West has wimped out on. I would ask Paul to consider his own neighborhood in Ireland and the persistence of dimensional beings beyond the human and the surrender in recognition of our limitations to any mental constructs defining reality as This or That. Jesus in and of himself seems to be a transcendent being here to teach and reconnect to eternal truths that had been again co-opted by the elites of his day.

However transcendence is by nature universal. To exclude or limit or define what other possible sources of light fall on the earth will not bring us toward cooperation, collaboration and the endeavor to turn away from these horrible conflicts and rape of our home and our family of life. A place in an ever growing number of beings yearns to find harmony and true relationship in concert with our home on this beautiful earth. We are in despair over continuous war and the for profit subjugation of life. We need not dwell on the particulars of our personal heartfelt beliefs. Rather dwell on manifesting the greater good for all, knowing we are not alone.