Political Theology: an introduction

A new short-essay series on what Political Theology is and why it matters.

I’ve written quite a bit about political theology, especially in The Mysteria, which is a series dedicated to the matter. However, I’ve never really laid out an easy way to understand the concept in any of those (often very, very) long essays.

Because it’s such an important framework for everything else I write, I’ve decided to start an occasional series of short essays explaining the concept through modern political problems.

This is the first of them.

What is Political Theology?

The core premise of political theology is this: our cosmologies determine our political frameworks. Or, put in a slightly different way, what we believe about the world shapes, defines, and limits our politics.

This maybe seems self-evident, but there’s another aspect to this which might feel a little harder to accept. Going back to those simplistic introductions, you’ll see I used the words “cosmologies” and “believe,” both of which are terms we’d generally associate with religions.

That’s the other crucial part of this framework, and why the word “theology” appears in the term. Now, of course, when we think of theology we typically think of all the esoteric religious concepts associated with Christianity, like the virgin birth, the doctrine of Original Sin, the trinity, and the bodily resurrection of the faithful.

None of these immediately appear to have profound influence on everyday political ideas, but many of them actually do. The easiest one to explain in that list is the idea of Original Sin, which generally states that we are all stained with the first sin of Adam and Eve (disobedience) and born into a state where we are already guilty of sin. In other words, as Paul in his letter to the Romans has it, “all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God.”

There are countless political consequences of this theological idea, and I’ll jump to one of the most relevant of them to modern political strife, contained in the statement: “all white people benefit from white supremacy.”

But how do we get from this Christian theological concept to a core tenet of social justice identity politics? It’s actually quite simple.

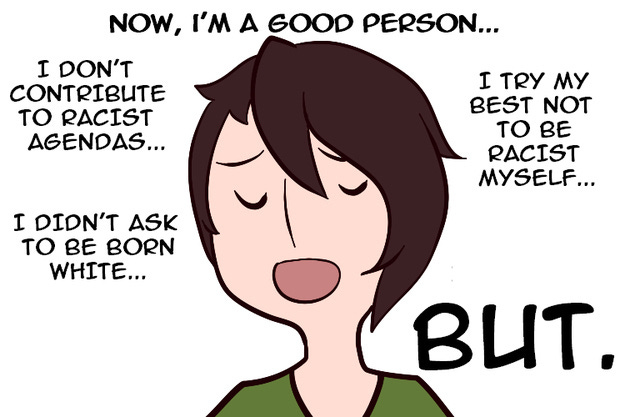

Original sin is ancestral guilt: those living now carry the guilt and responsibility for “sins” committed by their ancestors. Even if they would not have supported the actions of their ancestors, the mere fact that they are descended from them means they share culpability for their actions. Through no conscious choice of their own, every white person “benefits” from the legacy of slavery and subsequent institutional racism. They all have “white privilege,” even if they don’t want it:

The two panels above are great example of how these ideas are related to Christian theology, since they follow the same form often seen in evangelical pamphlets explaining why “being a good person is not enough to get you into heaven”:

The similarities between the Christian belief in Original Sin and the social justice identity politics belief in inherent privilege are not accidental: the latter framework arose within a society already steeped in that earlier belief. That doesn’t mean they are the same, or that social justice identity politics is necessarily Christian. (There’s definitely an argument to be made that it’s a Christian “heresy,” but that is something too complicated for this short essay.)

But What About Secularism?

At this point, though, you might be tempted to ask, “wait: because one of these is religious, and the other one is secular, how could they both be considered political ‘theology?’”

The answer to this is that secularism, also, is a kind of theology. One of the points I’ve made quite often in my essays, especially in The Mysteria, is that even when we claim to not believe in a god or gods, we nevertheless act as if we do.

Often enough, it just turns out we’ve replaced one idea of a god with another idea, as is the case with Democracy. In medieval monarchies, the king was believed to derive his authority from the Christian god, while, now, presidents and prime ministers are believed to derive their authority from “the people.” Here, “the people” functions the same way as the Christian god did, a source or a container for authority and power.

This idea of a container or a source leads to a really crucial thing we need to understand about political theology: cosmology. I mean something a little different by this word than the current definition, which usually denotes a scientific study of the origins of the universe. Instead of that definition, this is what I mean:

A cosmology is the way that one sees the world and the relationships of all things in it.

This is much broader than the scientific sense of this word, but it also includes that definition. A cosmology is not just how you think everything came into being, but also how everything that exists is “arranged” or relates to everything else. Those relationships or arrangements may be hierarchical (as in the medieval Great Chain of Being, which put god at the top and humans in the middle) or more lateral (as in many animist cosmologies where animals and humans were seen as kin or siblings). Also, whether or not one thinks those relationships are “natural” or “imposed” is part of that cosmology, along with countless other propositions.

What You Believe About The World Defines Your World

Another way of understanding cosmology is to think of it as a religious system (or theology), even if it is not explicitly religious and even if it rejects all precepts of what we would think of as “faith.” An atheist has a cosmology, just as a monotheist has one. Each takes certain things as given and inarguable. Though one might believe there is a singular god and the other might believe there are no gods at all, the conclusion of each is a foundational belief to the rest of their cosmology.

Again, though, cosmologies are not just about divine beings (or the lack of), but also how everything in the world or universe is arranged or relates to each other. A monotheist who believes everything was created by a singular god and an atheist who believes it all came about through impersonal forces might regardless come to the very same conclusions about certain other matters. For instance, both might believe that humans are innately selfish and violent, and therefore they might conclude that we need strong governments, laws, and prisons to keep civilization from disintegrating.

That’s because their cosmologies both include the same belief (innate human selfishness), which again appears to be very close to the Christian idea of Original Sin. Here, though, there’s yet another complication, because that Christian idea isn’t actually fully original to Christianity at all, but arose out of Jewish thought around collective guilt. In Hebrew monotheism, priests needed to sacrifice animals to atone for the sins not just of individuals but of the entire people, because the sins of one person made everyone guilty.

It’s very easy to see how this collective atonement/guilt idea shows up in the “secular” social justice identity politics cosmology. All white people, or all men, or all “settler-colonists” share together in the responsibility for — and the benefits of — oppression of black people, or indigenous people, or women.

That’s why political theology is important. Understanding how these older religious frameworks continue on into supposedly secular and non-religious political ideas helps us understand why these ideas have so much power.

Just as the belief in a vengeful god who would condemn you to an eternal lake of fire holds power over people and influences their actions, the beliefs that there is such a thing as collective responsibility or ancestral guilt holds power over us and shapes the way we see each other and ourselves now, and also how we relate to each other.

In future essays, I’ll look at specific examples of how political theology shapes current issues. I’m very open to suggestions for particular topics you’d like to see covered, and specific questions you might have.

All essays in this series will be free, but the much longer essays about political theology (the Mysteria) are usually pay-walled. Until 1 September, 2023, you can get 20% off a one-year subscription:

And also until 1 September, all books at RITONA/Gods&Radicals Press are 25% off, including mine. This is a great time to pick these up!

Sometimes I feel overwhelmed by the diversity and quantity of cosmologies, in your sense, that exist in the world -- I'm not even convinced that any two people have precisely the same cosmology; even what seems like a small difference can have a large effect, if consistently applied. Of course, intellectual beliefs and the beliefs one demonstrates through how one lives can diverge.

A question I've been considering for a long time is how people with different cosmologies can live together, or at least live without conflict, war, and violence, in a healthy way. It was Daniel Quinn in his book 𝘐𝘴𝘩𝘮𝘢𝘦𝘭 who pointed out that one of the underlying cosmological tenets of Western civilization is that "there is only one right way to live". It seems like this is everywhere nowadays in our politics -- everyone is trying to prove that they have the truth and are right; their way is the only way, and any other way is evil and terrible, etc.

How can we step back from this? But more importantly, how can we live together when we have such incredibly different cosmologies and political theologies?

Are you familiar with Rune Rasmussen's work? I think the content in this video speaks to some of what you are delineating here. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z8GKbimnMj8