(A quick update: the next installment of our book club on Silvia Federici’s book, Caliban and the Witch, will be published this weekend. Thanks for your patience!)

Yesterday, glancing intermittently at my phone between sets at the gym, I learned that the very final edits for my upcoming book, Here Be Monsters: How To Fight Capitalism Instead of Each Other, are complete.

These two things perhaps seem unrelated. After all, what does squatting while hefting 70 kilo (154 lbs) of weight on your shoulders multiple times, or repeatedly pressing 160 kilos (352 lbs) of weight with just the muscles of your legs and ass, have to do with leftism and identity politics?

For me, the answer is “everything.”

I’ve tried in various places over the years to tell this story, how I finally realized there was something really broken, self-destructive, and most of all self-defeating about “woke” ideology. There was no singular moment, however, but rather a quick succession of moments, each unfolding uncomfortable truths about my own life.

Many of these were recognitions of deep betrayal. When a close activist “friend” justified the physical abuse by my (self-identified non-binary) now ex-husband as a manifestation of my own “toxic masculinity,” for instance. When another activist “friend” — someone I’d hosted in my home and enthusiastically supported for years — stoked an internet crusade against me. When a group of people to whom I’d given months of unpaid labor tried to force me out of the publisher I co-founded and still run.

But just as many — and perhaps many more — of these moments were realizations about how I’d betrayed myself. At first slowly, and then suddenly like a flood, I began to understand how much I’d let others define who I am, what my life means, and what my existence is for. I did this to myself, over and over and over again, always and each time in the name of being a “good” leftist. Whenever anything about me was “oppressive,” I did everything I could to diminish it, to destroy that part of me, to restrain or silence or punish it.

What does diminishing yourself like this look like?

It looks like the picture on the left:

That’s a before and after picture. And despite what you might be inclined to think, the picture on the left is the “before.” It was taken just before I ran away from my abusive ex-husband at the end of 2019. The picture on the right was taken four months later.

A month after I fled that man, I was fortunate enough to be contacted by a therapist who agreed to work with me for free. I told him in our initial meeting that my abusive marriage had been the “perfect storm” of every one of my shitty ideas about myself, each one forming a bar on a prison I’d somehow managed to walk into voluntarily.

At the beginning, I assumed all these self-destructive ideas were only related to the way I understood love. To my deep surprise, I soon understood they shaped every other relationship and the way I understood the world: friendships, politics, work, everything.

The guy on the left side of that picture believed suffering was caused by “systems of oppression,” by “structures,” by “cis-heteropatriarchy” and “white supremacy” and “unacknowledged privilege.” He also believed, because he was constantly told this by those he surrounded himself with, that it was his role in life to undo those things, to constantly apologize for who he was and to make himself as small as possible so the “oppressed” could be liberated.

I remember one such moment, when an “oppressed” person whose yearly income and accumulated wealth equaled five years of my own, called me “a white-privileged working class equivalent of a trust fund baby.”

And I believed her.

Meanwhile, a man who would hide behind a non-binary (and occasionally, when he really needed extra oppression points, trans) identity punched me in the face, threw mugs at me, destroyed what little I owned, deleted contacts in my phone and hovered just outside the door whenever I tried to call my friends and family to tell them what he was doing to me. “Violence is the language of the oppressed,” he once said to me, in response to my request that he apologize for kicking me in the groin.

In Here Be Monsters, I mention a person whom I’ve renamed “Karen” in the book, a former friend. I’d told her everything that was happening to me, and she sent me Everyday Feminism articles that explained how the abuse was obviously my fault. Because the man identified as non-binary (and again, sometimes trans), it was “obviously” my cis-male toxicity which must be making him do such things to me.

And I believed her.

The guy on left side of the photos believed all of that. The guy on the right side of that photo still believed some of it, but was at least starting to wonder if maybe it wasn’t all true.

And then there’s this guy who is me now, years out of that marriage and that ideology, long out of that prison and long into freedom:

This guy stopped believing any of that shit.

I mentioned that the gym has “everything” to do with the book I wrote, but what I really mean to say is that the body has everything to do with it.

A core section of the book — in fact, what I think is the most important section — discusses the problem of ressentiment in identity politics. It’s the “vampiric gaze,” or Mark Fisher’s “vampire’s castle,” a social, psychological, and I’d also argue spiritual (as in the Evil Eye) force where we abdicate our agency. Then, like vampires void of lifeblood, we then drain the agency of others.

No one else is at fault for the prison I walked into, nor is anyone else at fault for my continued refusal to step back out. The door was always unlocked, but I convinced myself I was supposed to be in there all along.

To “train” an elephant, they chain it when young to something impossible to escape from. Despite eventually becoming so large as to break any bonds, because it became accustomed to never breaking free, it forgets to try again. It no longer understands how to understand its body, its massive strength, and all the space it rightfully takes up in the world.

Ressentiment is the body without agency, the passive “slave morality” that justifies inaction and cedes all responsibility to another. Agency, which is also sovereignty, is the only antidote to ressentiment, and it’s also the only antidote to the abandonment of self at the sacrificial altar of identity.

The body with agency is the body in the gym. It’s also the dancing body, the body of the witch, and the body in love. Such a body cannot be trapped in prisons, because it will not walk willingly into them. And such a body cannot stand in submission to abuse, because no abuse could ever truly make it submit.

This truth is woven throughout my upcoming book, and is the foundation upon which it is written. A friend asked me why, after all I’d seen done in the name of “leftism” I was still a leftist. Here Be Monsters is my answer to that question, because none of the ridiculous, self-defeating identitarianism of the “woke” was ever worth of the name “leftism.” We’ve all deserved something better, something that restores to us our agency and power and refuses ever to abdicate who we are and what we desire.

The book comes out 12 September, from Repeater Books.

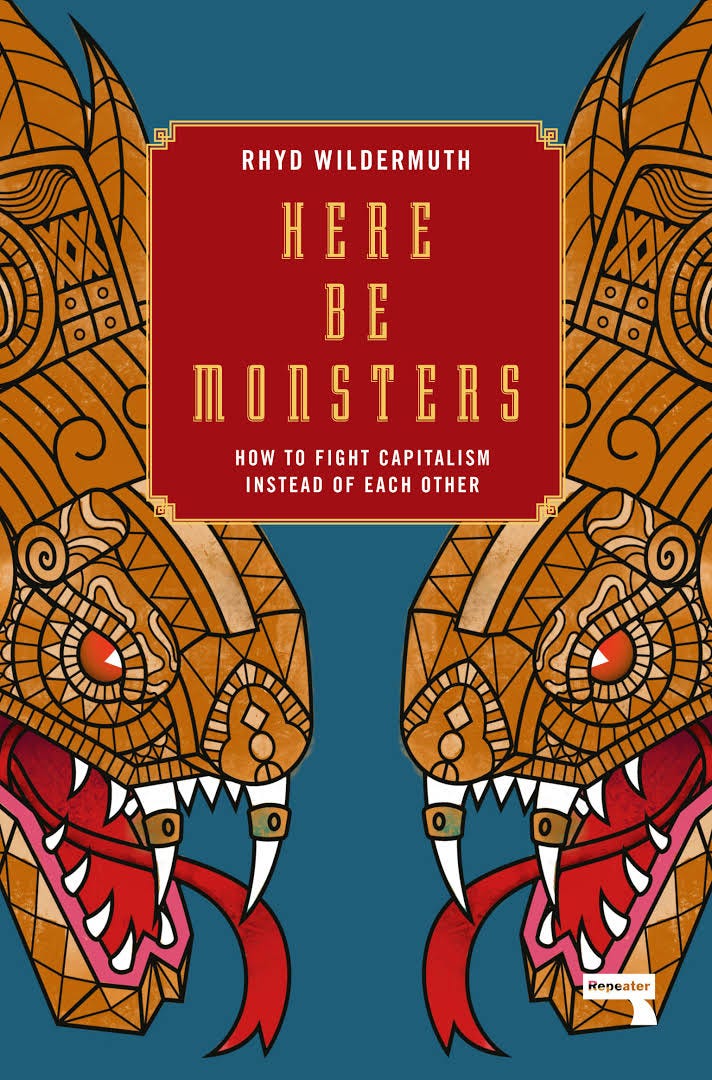

And here’s its cover:

The official pre-order page for the book is not yet open (though you can find some retailer pre-order options through Penguin). You’ll be hearing a lot more about this book very soon, and I’m thrilled it will soon be in the world.

In the meantime, if the body and agency interests you, it’s also a core topic in my book Being Pagan: A Guide to Re-Enchant your Life and also the course I teach on the book, which starts 15 April, 2023.

I identify really strongly with what you wrote here and it's not at all easy to break out of your own mindset and remake yourself!

I too was in an abusive relationship but with someone of a different race. He wasn't woke but he did constantly try to instil guilt and self-loathing in me for being 'elite', by this he meant studying the arts and loving books. Because of my willingness to self-flagellate, I cooperated in the struggle sessions and didn't dare express any of my creativity.

When we split up I spent two years painting virtually non stop after a 15 year break from the arts.

Another militant friend, whom I hosted over Christmas, spent her short stay subjecting me to an inquisition about whether my furniture was ecological, the food organic, if my parenting was up to scratch and essentially my credentials as a person of worth before working herself up into a rage and leaving during a storm. At first, the perceived ideological purity gives them guidelines to live by, and by enforcing these on others, they get to feel like they are serving a greater cause, but after a while their lives are defined by disputes that rob them of their joy and whatever remained of their sense of humour.

These conversations are really timely. Thank you, and by the way I am working myself up to signing up to the pagan course!

Congratulations on the great book cover, and more importantly, for getting free of the prison. Looking forward to coming to your UK book launch.