The Bones of Faro

A travel journal from the Algarve, Portugal

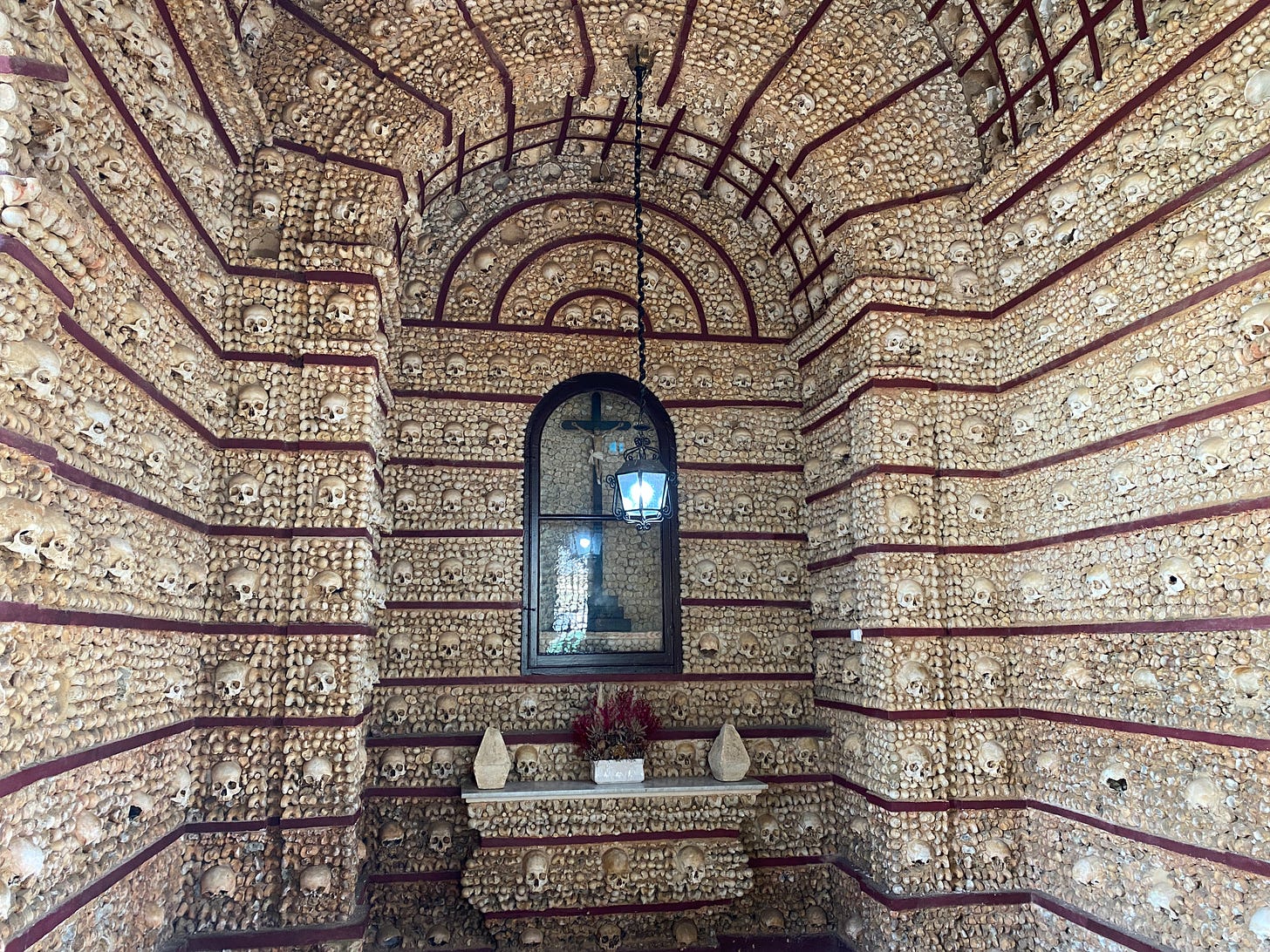

A bone chapel raised under a crimson sky: the world is much more strange, and much more Other, than we usually let ourselves notice.

I’ve just arrived home from a ten-day sojourn in the Algarve in Portugal.

It was my birthday, and also my sister’s 40th. To celebrate it, we, along with her family, our other sister, and my husband all stayed together in a large house on the cliffs overlooking the Atlantic.

Starting the trip a few days earlier than the others, my husband and I traveled first to Faro. Faro’s an ancient city — or town by US standards — originally settled by the Phoenicians several thousands of years ago. Later, it became a small port city of the Iberian Celts, and a little later part of the Roman empire. Waves of others controlled it over the last two thousand years: the Romans, the Visigoths, the Moors. Then, it was sacked several times by Anglo crusaders on their way to the “holy land;” later, it was sacked again by Portuguese Catholics purging it of its Jews, Muslims, and Pagans. And now, it’s being ransacked again, this time by capital.

Like many southern coastal regions throughout Europe, Faro is a chaotic mix of ruins both ancient and modern: old city walls and crumbling gates filled with tourist shops and restaurants, bordered by a melange of shoddily-constructed tenement blocks for the residents punctuated with newer hotels and condo towers for the foreigners. Both blessed and cursed with balmy weather, waves of tourists surge through its streets seeking a sense of life, then ebb back out just as quickly to the colder places where the money can be made.

There’s much to be critiqued about these patterns of tourism. In a brilliant recent essay, Chris Christou wrote:

Tourism is not just an industry. It is a worldview, a way of life that amplifies an already alarming affliction of being elsewhere, everywhere and, therefore, nowhere. It is the abandonment (and subsequent absence of) home, culture, and community. Everyone is a traveller, but whether by choice or force, whether at home or away, most modern people today are tourists, even in their own homes.

Christou gets to the precise problem with tourism: we’re also tourists in our own homes. Alienation is the default state of existence in modern capitalism, feeling “foreign” in the very places we call home. For Christou, the opposite of the tourist is the neighbor, the person consciously aware and actively participating in relationships with those around them. The tourist sees everyone and everything around him or her as a service, a transaction, an exchange mediated by money. Even land and its startling, breathtaking vistas become products to be consumed, optics to be captured and redistributed for algorithms which decide for us what’s worth looking at.

To say all this isn’t to also say we should not travel. In fact, I’d argue quite the opposite, as travel has always been a sacred ritual act for me since my first pilgrimage more than ten years ago. While thinking about this matter, I re-read the final entry of the journals I wrote for my second pilgrimage and smiled, remembering an insight that changed everything about the way I understood travel:

“Sometimes the inhabitants of those foreign lands, neighbors to great mysteries and cohabitants with the ancient gods of land, cannot see what you’re there to find. Perhaps it isn’t really all that strange — if we, before we travel, have failed to see the magic around us in our mundane lives of work/home/consume/sleep, then even those living next to cathedrals and shrines might miss the forest-in-the-wardrobe….

…opening the disused, rusty, overgrown gates of the Other in the lands they visit, the pilgrim must return, bearing mystic keys to unlock the gates of home.

That is, travel is a sacred act because it shows you how to see the sacred where you live. The stories you learn of the places you visit — assuming you learn to listen — teach you how to the tell the stories of the places you dwell.

Speaking of stories and sacred places, my husband and I visited a kind of Christian practice and site I’d long known about (and referenced in essays), but until now hadn’t seen in person: