I’ve almost always been a large guy.

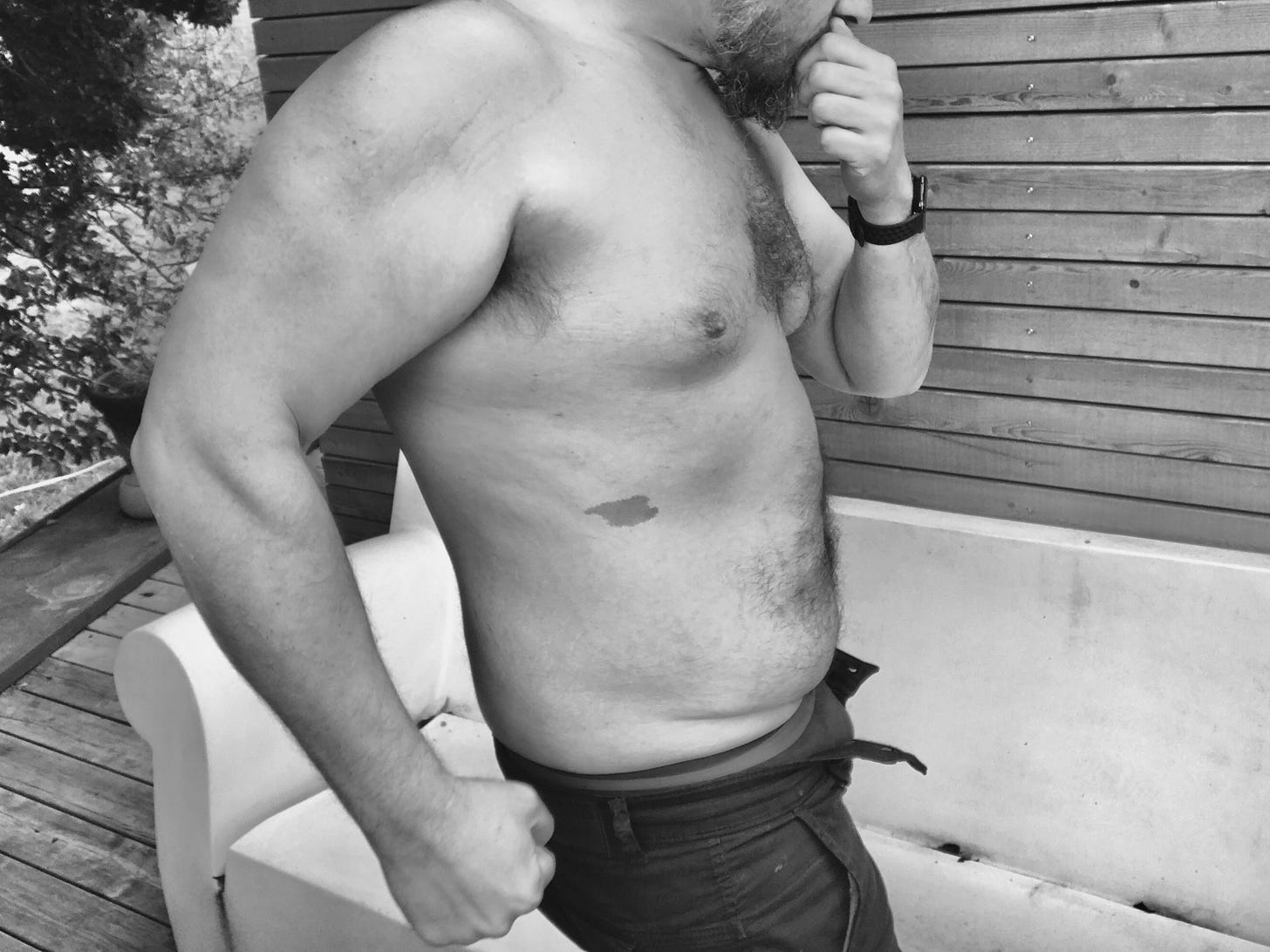

Currently, I weigh almost a hundred kilo, or 220 lbs for you Anglo and American readers. I’m 1.87 meters, or 6 foot 1-and-a-half.

I’ve been much, much bigger, and I’ve been smaller, too. Generally, my weight has swung between 10 kilos more and 10 kilos less1 than this, but there was a point I was 130 kilos after a knee injury in my late 20’s, and a time before that I was much thinner.

What this means outside of the numbers is that I’ve been quite ‘fat’ most of my life. Currently I’m much less ‘fat’ and much more ‘muscled,’ but I’d still be considered overweight by most metrics.

Being fat is not a very comfortable thing to be in modern society. Of course you get called fat when you’re young, especially in middle school, by other people who are also young. When you’re fat, kids will call you all sorts of things, and usually in groups where they can be heard well, a performance theatre of social bonding for the bullies and ostracization for the targets.2

Of Tits and Rocks

I can remember two specific moments of such shaming, and I’ll tell you those stories.

One of those was the stuff of nightmares, really. I don’t know if they still do this, but when I was in middle school (13 years old or so), schools ran a diagnostic test on students for scoliosis, a condition in which your spine becomes curved and twisted. It starts in kids aged 10 to 15, and it can be corrected when caught early. So, it makes sense from a public health perspective to mass-test kids in that age range.

Again, I don’t know how it is now, and I imagine in places with national health systems the testing is likely done by a doctor in an office. How is was done for us was much more how you might imagine the military or a prison might run such a test: in an open gymnasium, with boys lined up on one side and girls on the other, waiting in line to get examined by someone with a clipboard.

To test for scoliosis, you ask the person to bend over with their legs straight, and the person needs to be shirtless so their spine can be seen clearly.

It’s an awkward situation in itself, but I need to set the stage for you here so you can understand this moment. There were about 200 13- and 14-year-olds in the gymnasium, and the test was done in alphabetical order. My last name begins with a W, so I was one of the last ones to get tested.

Kids who were already examined stayed in the gymnasium, and were all lined up on a third side with nothing to do but wait for the others to finish. There was a privacy curtain set up for the girls, so no one could see them bend over for the examination. For the boys there was no such curtain, and the group who had finished—who again had nothing else to do—could clearly view that exam.

Okay. So maybe you can guess what happened next. By the time I was up and asked to take off my shirt, the vast majority of the students had finished and could see me.

When you’re overweight, bending over shirtless is kind of a messy sight. All your fat hangs down pendulously, a bit like the underside of a dairy cow who has recently given birth. It’s a sight to behold…and it was middle school.

So, inevitably, some kid in the crowd said something. I remember the exact words, actually: “wow his tits are bigger than my mom’s!”

If you’ve never heard the sound of laughter and jeering echo off the walls of a gymnasium for several minutes, I can assure you it’s quite loud. When that laughing and jeering is about you, it’s really quite an experience.

The rest of that year was pretty awful. I think I heard that joke repeated daily for the next month, and again at least every few days until the end of the school year.

There was another event that I remember very well. It happened the next year, and not in school but just after. To get home from the bus stop, I had to walk down a long street with three girls who also lived nearby. We were most definitely not friends, and they would sometimes walk behind me and call me names.

One day, I don’t know why, they started throwing rocks at me and calling me ‘fat pig.’ The rocks started as pebbles and their aim was quite poor, so none of them hit me at first. Then they picked up larger stones and hurled them, and one hit me hard on the back of the leg.

It hurt quite a bit, so I started running. Being fat makes running difficult, and super wobbly, and I also had a heavy pack full of books on my back and a clarinet in a case in one hand. Basically, not a very ideal running situation, and I wasn’t going very fast.

Another rock hit me, this time in the neck. It really, really hurt, so I tried to run as fast as my bulky body could carry me…and tripped.

I skinned my face and knee really badly in that fall, but the worst part was what happened to my clarinet. It had gone flying from my hands, and when it hit the asphalt the case broke and the joints shattered. That clarinet was the only thing of value I possessed, and I loved playing it, and my mother did not have the money to replace it.

I cried there on the ground as the three girls walked past, still calling me ‘fat pig’ and laughing.

“Fat-Acceptance”

I guess you can call those two events rather “traumatic.” From them, I learned that being fat was not a good thing, that fatness was something which makes you a justifiable target for social abuse, and that being fat is something you should be ashamed of.

I suspect lots of other fat people can attest to similar experiences and also to having reached similar conclusions that I did. The bulk of the body positivity movement3 probably consists of many people who can tell you equally disturbing stories about such situations, about how really awful those experiences can be, and how difficult it is to deal with the trauma of having mass shaming directed at your body.

When I first discovered that movement, I was pretty thrilled, like it was a movement made for me. Body positivity basically states that all bodies should be accepted as they are and that everyone deserves to have a positive self-image regardless their size.

That’s all damn good, actually. On paper, anyway. Unfortunately, like many other great social justice ideas, it’s not actually as good as it sounds.

There are really several aspects of body positivity, or several frameworks for it. Body positivity itself comes out of the “fat acceptance” movement in the United States, which worked to end shaming and what is often called fat-phobia. As a counter to the increasingly plasticized “ideal body” seen in capitalist marketing and journals, the movement—through the slogan “health at every size”—pushed for more representation of larger bodies and a rejection of tying the health of a person to their body fat percentage.

Again, this is great on paper. It definitely created a needed counter-balance to the sense that there was something inherently wrong or immoral about a fat person that would make them a valid target for social abuse.

One of the problems however is that having a lot of excess fat on your body isn’t actually healthy nor really very comfortable. I say this from experience, not from some distant theoretical perspective or from internalized social pressure: being fat can be really awful.

I only know this because I have been both very fat and not very fat. When you have a lot of fat, everything except the most basic daily physical activities feels like extreme exertion. You get tired and winded very easily. You sweat like crazy. Your skin chafes in really uncomfortable ways. You feel uncomfortable all the time, a general sense of unease that you can never really identify but you always feel.

And oddly, your mind works differently than when you don’t have so much fat. Your thoughts tend to be a bit sluggish, since the rest of your body is also sluggish. Complicated problems feel like too much effort to unravel, just as complicated and exerting physical tasks feel like too much effort to undertake.

Thin privilege?

Of course there are social difficulties that come along with being very fat. It gets frustrating to go some places or ride on public transport when the spaces created for humans to be in are standardized to smaller people. Riding an airplane is really awful, as is the frustrated look of the person next to you when they realise they’ll have to struggle to maintain the already small space they were allotted now that someone will be spilling out of the space they were given into yours.

To their credit, these kinds of social problems are what the body positivity movement focuses on. Unfortunately, they often miss what is an obvious mediator in such interactions: capitalist profit motive and industrial efficiency. Airplane and public transport seats are small because the more people they can fit into these expensive machines, the fewer they need to provide to turn a profit or not lose money. Basing such spaces on a smaller model of human means they can add a few more seats and charge premiums to those for whom those spaces are too small.

Often times, that mechanism is ascribed to “fat-phobia,” and those who fit into those spaces and therefore do not experience the sense of being stuffed into a chair with your fat rolls pinched by the armrests4 have “thin privilege.” That is, they have some inherent advantage over fat people that they do not recognise and from which they constantly benefit.

Here we can see how body positivity and fat acceptance is actually a part of the larger woke ideology, rather than a politics based on material conditions. Fatness becomes an oppression category, rather than a bodily state. To be oppressed, of course, you need an oppressor, and that oppressor class is composed of all the people who are not fat.

For a long time, I believed all this. It helped me feel better about being fat and gave me a useful (but untrue) narrative that helped me find some reason for the shaming I had experienced as a fat teenager. Those girls threw rocks at me and that kid compared the fat hanging off my chest to his mother’s tits because they were part of the thin oppressor class. I was a righteous victim, targeted because of some innate trait about me that others hated and wanted to punish.

Again, this helped, but only up to a point. Because, as I said above, being fat is really kind of awful, and not because other people think so. It’s uncomfortable to feel at war with your body, to feel always full yet hungry, to be tired all the time, to feel like you are constantly stuck in a muddy mire unable to move through the world at will.

Agency and Industrial Capitalism

Worst of all, it was something I had complete control over.

Yes, of course there are people who have physical conditions which cause them always to put on weight, but the basic mechanism of how much you eat versus how much you do is a hard constant throughout all human bodies. No matter what physical condition you have, if you eat less food than your body needs for what it is doing, you will lose fat. No matter your social situation or disability, if you eat a lot more food than your body uses, you will get fat.

How “efficient” the body is at using what it consumes isn’t a constant, however. This is where human agency comes in, and also the physical effects of industrial capitalism. Eat a lot of processed food and your digestion changes, especially if what you’re eating is full of modified sugars like high fructose corn syrup. Among other things, that can lead to diabetes, which makes your body less good at using glucose, forcing it to store its excess rather than eliminate it.

Also, the amount of stuff you do changes your metabolic rate. If you’re active often, the body will start using more of what you’ve eaten and what you’ve stored as fat, resulting in a sense that you have more ‘energy’ and therefore are more inclined to keep being active. On the other hand, sit around all day, walk only to your car to go to work and to walk back from your car, and you’ll feel even more of a desire to stay sedentary.

In both of these places, industrial capitalist society has a significant effect on our bodies. On the one hand, its factories pump out low quality and highly addictive food that is often cheaper and more convenient to purchase and consume than anything better for us. That food changes your metabolism and the way your body uses food, leading to many health problems and making it much more likely you will be fat. On the other hand, it creates urban spaces, jobs, and physical barriers which urge us to be more sedentary and less active, which again makes us unhealthy and makes it more likely we’ll become obese.

To add insult to injury, it then tries to sell us products to fix the problem it is helping to create. Diet plans, weight loss programs and pills, and a general marketing trope of an unrealistic (and equally unhealthy) ideal skinny body all redirect us back into false solutions and more bodily alienation.

But you won’t actually hear any of this discussed in the fat acceptance or body positivity movement. Instead, being trapped in the woke ideology, it can only really address the social rather than the physical. Thus, the problem isn’t industrial capitalism, the kinds of food we are eating or the kinds of jobs we are working, but rather an imagined oppressor class called “thin people.” It isn’t that we humans have become alienated from the body and our agency, but that thin people won’t date us and that Versace didn’t feature plus-size models until this year.

In fact, there’s a pretty dark side to the body positivity movement tied deeply to the problem of ressentiment. You can see it especially on social media, where people who are thinner, who go to gyms, or have chosen to live lifestyles that embrace their bodily capacities are castigated and ridiculed in the exact inverse way that fat people sometimes are.

The Trace of Trauma

Also, to the body positivity movement, suggesting that avoiding certain kinds of industrial foods and increasing physical engagement in the world is labeled “fat-shaming,” because it is seen as a judgment on the value of fat bodies.

Rather than just dismiss this, I’ll admit that something interesting is going on here that I know intimately. This is the experience of “the trace” in ressentiment, the sense that a trauma is being constantly re-enacted in the present even though it isn’t.

At the beginning of this essay I mentioned two concrete examples of being shamed for my fatness. Interestingly, though I feel as if there were many, many more, I’ve come to understand that actually it was not a very frequent occurrence. Regardless, I still felt as if people were constantly shaming me and that my fat body was hated by all those around me.

I never understood why there was a disconnect between the actual events of being shamed and my sense of being shamed much more than I was until a peculiar interaction with someone.

I was in a group forum dedicated to discussions about weight training, lifting, and other related things. One of the people in this forum repeatedly complained about how every time he went to the gym he could hear everyone laughing about how fat he was. So he left that gym and went to another one in the same city, but experienced the exact same thing: everyone made fun of him.

The others in the forum expressed sympathy for his situation, suggesting he talk to the gym managers or try another one. A few suggested gyms that they went to, where they never witnessed any kind of shaming. In reply, he told them he had tried those and experienced it there, too, and angrily accused them of being too privileged to notice when fat people were being shamed.

If you’ve never gone to a gym, you might not know this: everyone in every gym I’ve ever been to is much too busy to spend time focused on someone else. If anything, gyms are probably the last place you’ll ever experience other people jeering at your weight, because they are all there to change their bodies, too.

The thing is, the first few weeks of going to the gym, I thought everyone must be laughing and making fun of me, too. Objectively, no one was, but it took a long time to shake that feeling because I felt that way all the time when I was younger, too.

Again, it’s a core mechanism of ressentiment, the “trace” of trauma which causes us to re-narrate social interactions in a way that feels fully true but objectively is quite false. While there are absolutely people who will jeer and insult people for being fat, they aren’t really all that common. Also, they are quite often reacting to their own traces, the same way that someone who calls every guy a “fag” is likely reacting to internal fears about being seen as gay.

Objectively, very few people in my life cared that I was fat. Few of those kids laughing at me in the gymnasium really thought I was any less of a person because of my weight, and 27 years later I find myself chuckling a little at that kid’s joke about me (which was also an awkward joke about his mom, too). And those girls who threw rocks at me probably had a really shitty home life and likely don’t look back at that moment with fondness, if they even remember it at all.

I suspect that the situations of other fat people are similar. While I once believed there was an oppressor class of thin people for whom the world was designed and who were constantly causing me emotional harm, I realise now that most people are just human and just as alienated from their own bodies as I was.

That is: what I thought I was feeling from others was only what I was feeling about myself.

Being Body Again

Unsurprisingly, my decision to start going to a gym four years ago resulted in several instances of attempted shaming like what I experienced as a fat kid in middle school. It of course felt different, because I was 40 instead of 13: twenty-seven years later, I had learned that shame only can affect you if you integrate it into yourself. The insults were still attempts to shame my bodily existence, but I no longer cared what others thought.

This is actually the key to a true positivity regarding the body, rather than the ressentiment-drenched fat-acceptance movement. What is crucial is not how society judges the bodies of individuals or groups, but rather how intimately each individual experiences being a body.

Whether you are fat or skinny or whatever, the core truth is that you are your body. Also, you are the only one who has full agency over its existence. To change how your body manifests in the world is to change how you manifest, and you are the only one who can do that.

In the end, this is really about desire. I am now much more muscle and much less fat than I have ever been because I desire this. I don’t desire this because others demand it of me, or because I think it will make me more desirable or less shameful in the eyes of others. It’s what I want, and it’s become pure delight.

Desire leads me to go to a gym where I push and pull really heavy things around for an hour. And then I go again two days later and push and pull slightly heavier things around, and then again, and again. Doing all this tears muscle which heals in a way where it becomes bigger, which feels physically amazing not in spite of but because of the accompanying pain. The ‘burn’ you hear gym people talk of is an amazing sensation, the body stretched to a limit further than its usual experiences but just before the breaking point.

Others have written of this much better than I can, but this physical strain, testing, and exertion changes the way you think, too. Lift an impossible amount of weight over your chest or push a much more impossible amount of weight with your legs and you cannot help but try other impossible things as well, because “impossible” doesn’t mean what you thought it did any longer.

Really difficult things in your life don’t get any less difficult, but you approach them differently. When I was very fat, “really difficult” meant “not worth the effort.” Now, it means, “oof…okay…dammit…fuck why not?”

The meaning of failure has changed for me, too. I’ve been trying for six months now to do pull ups without any assistance.5 Years ago when I tried, I quit and pretended I didn’t really want to. Now, I still cannot do them without assistance, but I keep trying and find I need less and less counterweight.

It’s the same with other stuff in my life. There are all kinds of things I failed at and quit. Now, I’m trying them again, and still failing at some of them but getting a little closer to not failing. And that feels fucking amazing.

I write all of this not to tell you that you should go to a gym or change your body weight or what you eat. Instead, this is to tell you what it feels like to enjoy being body again, to no longer care what others think of you as body and to no longer cling to convenient but ultimately false notions of “body positivity” or “fat acceptance.”

Though it might feel good for a little while to believe thin people are oppressing you and that society must change in order to accept you, this still displaces your agency and postpones the necessary and beautiful work of embracing yourself as body.

As for me, others might find that this work begins by letting go of the trace of shame you integrated into yourself when you were younger. Someone might have said you were too fat, or too skinny, and you believed them. More so, you believed that others probably felt the same way, and that what other people believed about you was somehow important to who you were and your sense of self.

It wasn’t important, though. And the whole world isn’t arrayed against you.

The world is full of more than 7 billion human bodies struggling to understand what being bodies means, and what they think of you will never matter more than what you think of yourself.

1 kilo is 2.2 pounds. I do this math in my head all the time, so I’ll let you try from here on out.

Woke ‘call outs’ and Antifa ‘deplatformings’ are just adult versions of this middle school dynamic. Instead of ‘fat,’ someone is ‘problematic’ or ‘cryptofascist,’ but the mechanism and goals are the same. Basically, wokeness is just middle school for adults.

That pun was absolutely not intended but I’m keeping it.

It’s a really, really awful feeling by the way.

It’s kind of hard to pull 100 kilos of human body up by just your arms and back muscles alone.

I’m really enjoying your writing on bodies and being embodied. As someone who grew up with ‘thin privilege’ it has taken me a long time to feel comfortable taking up space in the world, and I appreciate my body settling into a healthier if less desirable size as I mellow into my late 30s.

I realised pretty early in my adult life that I need to claim agency over my own health – I was suffering from things that mainstream healthcare didn’t take seriously, so I just decided to get to know my body better and deal with it my own way. Instead of feeling stuck in an uneasy partnership with my body, I have learned to feel grateful for it, and to be aware of what it tells me about the state of my relationship with food / environment / movement / sleep among other things. And, yeah, after being taunted at compulsory Physical Education classes throughout school, I’ve learned pretty late in life that strenuous physical activity can actually be fun.

This essay is especially timely because there is more than a hint that many of the bad health outcomes in the U S of A related to Covid stem from the population being overweight. I’d suggest that many of the side effects of vaccines may be tied to overweight, too. It makes one rethink “fat acceptance” as public health.

I also can’t say enough about how horrible the introduction of such trash-as-food as cottonseed oil, hydrogenated fat, high-fructose corn syrup, and soy oil have been for Americans and their health. (Speaking of U.S. capitalism in action: Crisco!)

Into the essay:

“This is the experience of “the trace” in ressentiment, the sense that a trauma is being constantly re-enacted in the present even though it isn’t.”

Excellent observation. It is at the core of James Hillman’s book, We’ve Had a Hundred Years of Psychology and the World’s Getting Worse.

Hillman and the Jungians say: Recognize the wound. Heal it. Live with the scar.

Ressentiment says: Keep the wound weeping.

The myth of Philoctetes says: You have to endeavor to close the wound, or you will never get off the island (where you are forced to live alone) to engage your destiny.

And W.H. Auden pointed out that every writer (that includes you, R.W.) has a wound of Philoctetes. But it cannot be a festering wound, or one can never be productive. There is a wound with a scar in a writer’s way of doing things.

“Whether you are fat or skinny or whatever, the core truth is that you are your body. Also, you are the only one who has full agency over its existence. To change how your body manifests in the world is to change how you manifest, and you are the only one who can do that.”

This paragraph is important: There is no mind-body problem. Please tell queer theorists and gender theorists to stop trying to solve the mind-body problem. The mind and body are one thing, somehow. The brain and the brain-connected eye are consciousness, somehow.

So: Lecturing us on our separable sexuality, genitalia / equipment, psychology, and immortal (!) soul is the leftovers of religion. Something from the back of the refrigerator of ideas. One cannot separate these things, even though we are composite creatures, as Buddhism tells us. Why we are engaged in warmed-over Platonism now is beyond me.

Thanks for the words—and, yes, the photos. I was overweight much of my life, and it isn’t easy. I’m now in a region of Italy where the body type for men is tall, slim (not bulked up, but not skinny), and long arms. Luckily, oddly, remarkably, that is where I am now bodily.