Arriving Where We Started

A photo essay

Please note: this essay is much longer than email will allow you to view. It’s instead best viewed on the site version, which can be viewed by clicking the post title.

Also, this is the second part of a two-essay travel journal. This is the link to first one:

And one more note! There’s one more day left to sign up as a paid supporter of From The Forests of Arduinna at a reduced rate. You can become a yearly supporter for 20% off or a monthly supporter for 10% by using the following buttons:

Yearly:

Monthly:

“We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

Through the unknown, remembered gate

When the last of earth left to discover

Is that which was the beginning…T.S. Eliot, Little Gidding

As I write this, the tasseled branches of young willows lining a small stream outside my window sway gently in a very subtle wind. They are in full leaf now, a fullness which made everything seem quite strange and new when we arrived here last night, 3000 kilometers and two weeks since we left.

I am home now, but as after all beautiful journeys, it is as if I have arrived somewhere completely new. The light through the windows had changed, as had the view those windows, our voices echoing off the walls of a home which felt like a chapel in a forest. Two weeks before, the trees were just loosing their pollen into the air, the vines of wisteria and grape on our balcony finally reaching their tendrils towards the light now that the last frost had passed. Two week later and no remnant of spring’s tentative hesitation lingers in their foliage, and only a slight morning chill suggests there was ever any doubt about summer’s arrival.

Days Six, Seven, Eight, and Nine: Split, Croatia

The city of Split, from which I wrote the previous installment of this travel journal, boasts the largest intact remains of a Roman Emperor’s palace. While the Flavian Palace in Rome is mostly ruins, much of the original structure of Diocletian’s Palace is still visible and still in use.

Emperor Diocletian ordered it constructed sometime in the last years of the 3rd century, and its purpose wasn’t that of imperial rule but rather retirement. You by now certainly know I’m not much into empires and their rulers, but Diocletian’s story is a particularly fascinating one, since his rule marked the true end of pagan Rome and the beginning of Christianity as a violent political force, rather than just a religious belief.

Diocletian instituted several bureaucratic reforms meant to keep the Empire from imploding in upon itself, especially the “Rule of Four,” which instituted four rulers (two emperors and two generals). The intention was that by distributing power across four people, the previous violent campaigns to seize power over all of Rome could be avoided.

Diocletian co-ruled Rome with Maximian (who ruled the Western half) until retiring to his palace, where he spent much of his time gardening. After voluntarily abdicating, his system completely fell apart, leading eventually to the suicide of his former co-ruler, several revolts, and the ascendancy of Constantine. While much of this happened, Diocletian repeatedly rebuked demands he return as emperor, stating that the garden he was growing made him much happier than ruling over Rome ever would.

The remnants of Diocletian’s temple to Jove are the most intact of the three pagan temples which he ordered built within the palace walls. As with most other ancient sacred sites, it was repurposed by Christians and is now the Cathedral of St. Domnius, the oldest Christian cathedral to exist continuously in its original form.

Much of the rest of the sprawling palace remains intact as well, though of course the life inhabiting it is vastly different from its original life. In the forests of the Pacific Northwest, there is phenomenon known as a “nurse log,” trees thousands of years old which die and fall to the forest floor. As the trees slowly decompose, other trees grow into the rich compost composing its corpse and use its structure as a foundation for their growth:

It is the same thing with Diocletian’s Palace, which has been continuously inhabited after its original owner’s death. Homes and shops were built using the palace’s strong walls as one of their own, with levels added after the original roof collapsed and more structures built outside its first borders.

Almost two thousand years of people walking through those streets has made the stones underfoot (most of them the original ones) so smooth as to be slippery even when completely dry. Many of the streets are quiet narrow, and then you suddenly stumble into a vast open space you hadn’t expected. Of course, it’s a quite busy place, and everything is all restaurants, cafes, and boutique shops, but all that commercialism is nevertheless dwarfed by the ancient stones which have outlasted countless empires.

(I filmed a video of my husband walking through the streets, but unfortunately Substack does not allow video embeds from Instagram. It can be seen here.)

Split was our longest stay of all our destinations. We’d rented a small but ample apartment for our time there, which was so close to the palace it felt it ought to have been much more expensive than it was. Croatia isn’t yet part of the Euro currency regime (it will be next year) and prices after conversion for groceries, drinks, and restaurant meals were only about 70% of cost in any of the other cities we visited, meaning we could splurge on some things we’d never feel comfortable paying for at home.

One of those more opulent moments was at a restaurant we were charmed into, as if by fae or sirens. We’d been stumbling around after one of our long days at the beach, unsure of where to eat, and out of nowhere a beautifully dressed woman lured us into an empty courtyard terrace, seated us. Suddenly another charming woman, a lesbian, was suddenly serving us exquisitely complex Italian dishes the size of which would barely feed a child yet the taste of which could feed an entire civilization. I have no photos of our meal, and I’m sure any I might have taken would have revealed only flower petals and sand upon a table. Nor am I even certain the place really existed, and I have only my husband’s shared recollection to assure me we’d not been dreaming.

In my previous travel journal, I mentioned we were within stumbling distance to a popular beach. We found an area a little out from it to go swimming but still found it really too crowded. Fortunately, the next day we found a beach much farther away which was less full of screaming children and drunk adolescents and whiled much of the day there, and then again a little farther still two days later.

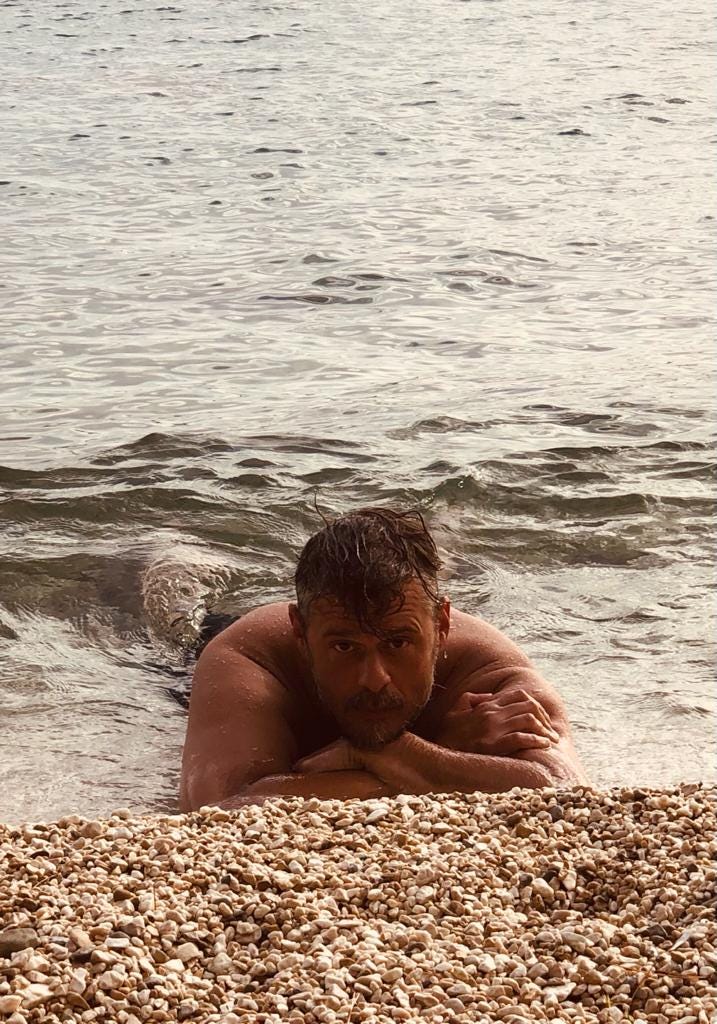

The ocean by Split becomes that clear Mediterranean blue-green for which more southern European beaches are known. The brilliance of staying there rather than elsewhere—and at the time of the year we stayed rather than later—is that it is less known and thus less touristic, though the trade off is that the water’s colder than what you’ll find in Greece or Sardinia. For me, thanks to those extra kilos of weight I gained from writing that manuscript (more than a quarter of which are already gone due walking almost 20 kilometers most days), the water felt perfect after only two minutes of adjusting. My husband, being much thinner than I, wasn’t able to endure it as long unfortunately, but he was quite happy with the intense sun on the shore.

I floated for hours on the last day, staring at the sky and the wild coastline. Massive Mediterranean pines cling to the white cliffs along the shore, and in places there are Roman and Greek ruins jutting out into the sea such that its impossible to feel you are just merely at the beach.

Split was the first time I’ve been in any body of water for anything beyond a bath in at least four years, perhaps even longer. The last time I remember swimming in an ocean, I was camping on the shores of Bretagne seven years ago, though I’ve waded across a few rivers in the interim. I’d missed it deeply, and the very last day it felt almost profane to leave the water after so long without it.

That day we walked our final long walk through Split, ate dinner, met up with a new friend, and listened to his stories of about life in Croatia. I’ll write more about this in an essay later this week, as his tales were part of a much larger challenging motif about western European and American ideas about identity, freedom, and especially sexuality and gender.

Day Ten: Return to Ljubljana

When we had first envisioned our honeymoon road trip, Split had often seemed like its final destination or ultimate goal. It wasn’t, though—it was only the place we intended to stay the longest.

Still, leaving felt a little sad for me, mostly because we were leaving the ocean. I’d forgotten how much of my life had been lived within sight of it, and also within sight of mountains. Neither of those were within view during my few years living in France, nor are they close to where I live now (though as my husband often wryly jokes, we need only wait a few decades for the ice caps to melt before we’re closer).

We’d also originally planned to visit Zagreb in Croatia, though we’d purposefully not made accommodation plans for the city in case we changed our mind. That was indeed the case, as we realised we both liked Ljubljana so much we’d prefer to return there rather than try to discover a new city for only 24 hours.

The drive north was as beautiful as it had been when we’d taken that route south. As I mentioned, I do not drive, but my husband’s account of the highways in Croatia was that they were the best maintained with the least chaotic traffic. When driving again later in Germany, he said many times, “I miss driving in Croatia.”

There are quite a few tunnels along the highway between Split and Croatia’s border with Slovenia, a point which I mention for two reasons. I’m not sure exactly why it started, but when we arrived at the first tunnel on our drive south into Austria, I kissed my husband, and then kissed him twice on the second one. From then on, I kissed him once for each tunnel we’d driven through including the current one, which meant by the time we arrived in Split I kissed him 55 times. We reset the count on the way back, and of the next 45 tunnels, at least 20 of them were in Croatia.

And in case you’re curious and like obscure mathematicians like I do, thanks to reading a book on Carl Gauss as a child it took me only a few seconds to figure that I kissed my husband 2575 times in total for tunnels alone. 1

The second interesting matter about tunnels is something I noticed after the third one we entered in Austria. I wasn’t sure I’d seen it right, so I had to look again the next one, and by the sixth tunnel I was finally certain of what I was seeing.

In each tunnel where I looked for them, which often meant taking a brief pause on the barrage of kisses, there was a virgin shrine. Some of them were quite simple, some much more elaborate. They were usually pale in complexion, though I’m pretty certain I saw a few dark virgins as well, leading me to suspect that the shrines are a continuation of old European pagan customs regarding chthonic goddesses. I don’t remember the historian who first directed me to this, but the cultus to black madonnas persists everywhere in Europe where pre-Christian veneration of subterranean goddesses was evident.

I’ve not yet had time to research this more since being back, nor was I able to photograph any of the tunnel shrines from the car. What’s most interesting to me is that they are not set up in places where anyone can visit them—it would be too dangerous. Thus, they are placed there the same way that certain sacred stones or other objects were placed in foundations of structures as a kind of protective ritual, rather than a site of reverence.

We crossed the border into Slovenia this time without any problems, though we’d become so worried that we stopped immediately after crossing to calm down and smoke a cigarette. Though I’m official in Luxembourg and a residence permit has already been issued, it wasn’t ready to pick up until the day after we had planned to leave on our trip. Instead, I had a paper récépissé, which I was assured would work fine at the borders but of course such things rarely do. The complication was that my previous visa in France had expired and it was the last stamp in my passport, meaning that border guards might try to bar me entry for having overstayed an expired visa regardless the current valid one.

The drive through Slovenia is also quite beautiful, filled with little chapels and distant castles. The primary route to Ljubljana is on a very narrow road through forested mountains and is a bit stressful, especially because it is used also by trucks and bicyclists. Fortunately we were going somewhere already familiar to us, and though our accommodations were more expensive and less scenic, arriving in Ljubljana felt really, really good.

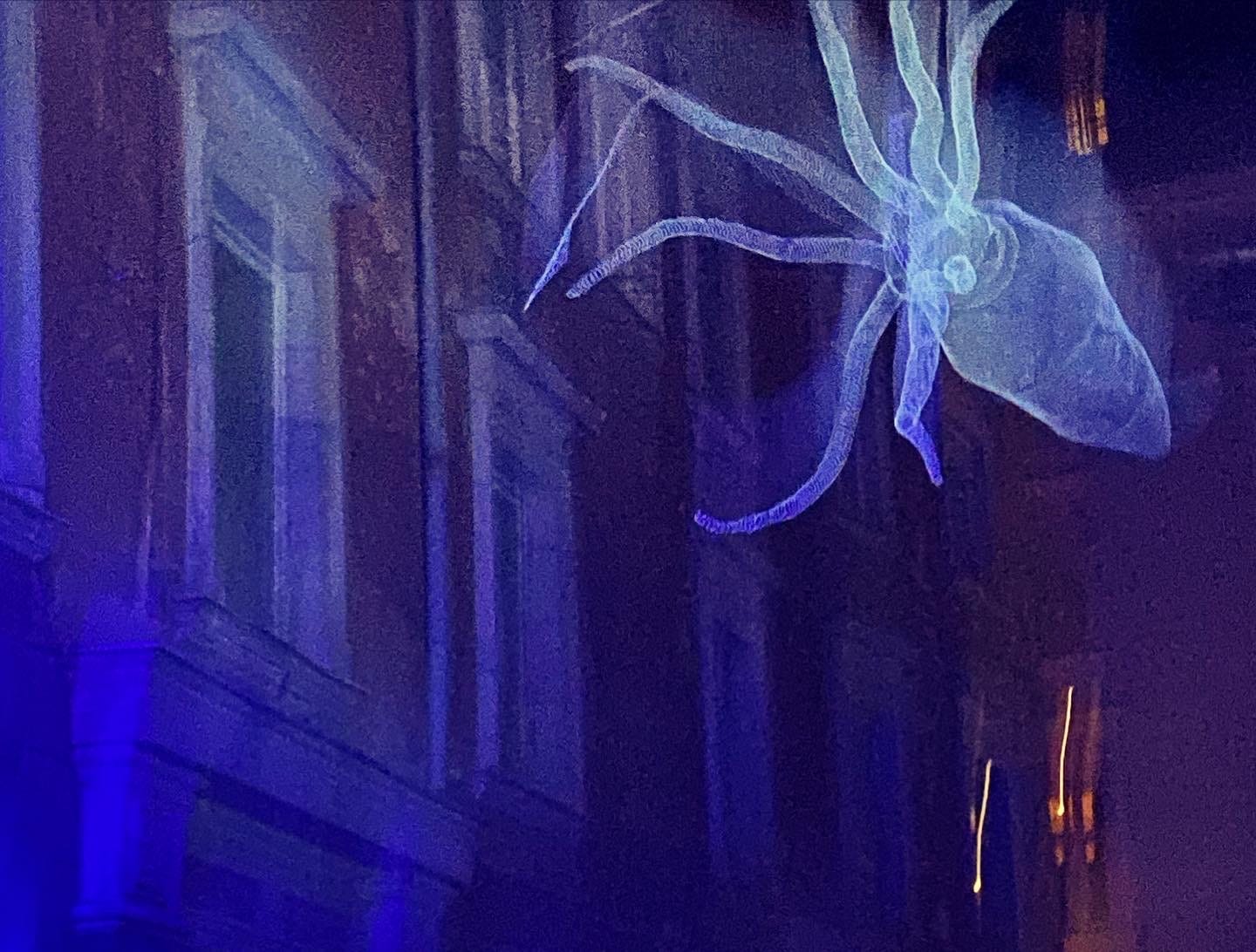

We returned to a restaurant we’d liked a lot, not because of its food but the servers, and then later walked through the city at night to a bar we’d visited both of our previous nights in the city. It’s the only ‘gay’ bar in the city, and is not officially gay, and we learned that night it was previously attacked in its former iteration. The mayor of Ljubljana then gave the owners space to re-open within part of the mayoral palace, giving it more protection but also dulling its former edge a bit.

One of the conversations we had with someone that night will also be part of the topic of that essay I mentioned I will write, but suffice it for now to say that some “eastern European” gay people see attempts to adopt American political conceptions on gender and sexuality as a kind of global colonialism, a theme we heard in almost every city we visited on our trip.

Day Eleven: Ljubljana to Salzburg

We drove again through the Austrian alps for several hours to arrive in Salzburg. As in our earlier experience driving to Graz, Austria, the views on the highway are breathtakingly beautiful. We listened to a lot of Wagner and Beethoven’s most bizarre, chaotic, and brilliant piece, Große Fuge, while mass walls of stone and Hapsburg fortresses passed on either side of us.

There was never a moment on our journey that we felt disappointed, but Salzburg was absolutely our least favorite stop. The reasons for this require another essay, but a short way of explaining the feeling there was one of chaotic social breakdown. I encountered the only aggression on our trip there, a man posturing menacingly after he saw me kiss my husband just after we took this photo:

More generally, it all felt discordant, like the much vaunted multiculturalism of European liberalism had there become mere cacophony. Another strange experience had occurred later that evening outside a rather depressing gay bar. An immigrant after asking me for a cigarette then showed me a credit card he’d “found” and asked me where he could try to use it.

Salzburg had for me the same angry atmosphere of Paris, a city I greatly dislike. There, my brother-in-law six months ago had his wallet stolen out of his pocket and cards by an immigrant petty street-crime cartel: they steal credit cards and then run to nearby shops to buy easily resold items before the victim has a chance to report the card stolen.

We were both honestly happy to leave Salzburg for our next destination.

Day Twelve: Salzburg to Stuttgart

We arrived in Stuttgart while a peculiarly odd and slightly amusing event was taking place. The day after Ascension in Europe is “Catholic Day,” during which churches and church-related organizations set up recruitment tents for pilgrimages and hold concerts to get teenagers excited about the Pope. It’s as silly as it sounds, and has all the elegance and festival feel of a middle-school science fair. One really bored looking old man in front of a small cart offered the devout a chance to win a bike if they could correctly answer all the questions in a Catholic Quiz, while some really not-very-amazing aspiring catholic rock musicians tried to inspire a very bored looking crowd.

Stuttgart is a great city despite all that, and has almost a Berlin feel. Our hotel was just next to the small red-light district and one of the oldest gay bars in Germany. Though there were quite a few gay bars, we only visited that one, wanting something to wash out the taste of the tragic Salzburg bar we’d visited the night before. That didn’t work, and I had a strange panic attack while there, something I haven’t experienced in years. I’m still not certain what happened, but it just felt extremely necessary to get out of there as soon as possible.

Stuttgart itself at least returned the sense that Europe was ‘okay,’ that it wasn’t all just immigrant and nativist conflict and street aggression. Germany also has done more work to at least try to offer paths to integration than Austria has, and the economy is still robust enough (unlike France) where it can offer enough work for those who might otherwise be tempted by street crime.

I don’t know if it was the city itself or the fact that we’d been together non-stop for 12 days, but it was in Stuttgart where I really began to realize what a relentlessly amazing and intriguingly complex man I’d married.

Honeymoons are so named because of an ancient European pagan tradition. After a couple had married, it was expected of the father of the bride to provide the couple with enough mead (thus, ‘honey’) to keep them both drunk for an entire month (moon). It was a kind of ritual, meant to make sure the time after the marriage went smoothly and happily enough that their bond was sealed.

Though we drank no mead, by the time we were sitting together at a Greek restaurant in that city, the ritual made sense. All the stress of work and everyday life had completely faded and we could see each other as we really are without all those things we have to be or find ourselves becoming to others.

Day Thirteen: Strasbourg

The shortest leg of our 3000 kilometer road trip was between Stuttgart and Strasbourg, and it was the only city we both knew intimately. 22 years ago, he became a university student there. 18 years ago, I visited Strasbourg for several weeks and made an instant friend with whom I still keep in contact and have visited several times since. It was the perfect place from which to start our journey back home, because Strasbourg has also felt like home. He left university three months before I first arrived, but we knew most of the same places and our lives had previously intersected in fantastic ways.

I remember having the sense that we were two dogs suddenly let off leash. One of my feet hurt rather significantly from a tendon injury, but I nevertheless felt like I was practically running to sniff all the old corners I knew, corners he also knew and smelled out without needing his sight.

We walked more that day than any other day of the trip but never really felt tired. Strasbourg had of course changed since we’d each last visited (he three years before, while four years for me). It was more full, and more gentrified, but many of our old haunts were still there.

One of those, a bar we’d both frequented quite often, had changed in a suprising and rare way. It’s often that a gay bar later shuts down and is replaced by something more bourgeois. However, an old Irish punk bar called Pub Nelson had to our complete surprise become a gay bar. It was there where we spent much of our evening with my friend Duf, the one I’d met 18 years before.

The story of how we met is one of my favorite stories of any meeting. I’d been traveling with a boyfriend, and we’d found ourselves sitting next to a group of loud and interesting looking punks at a bar. One of them approached us after a few minutes and asked if we were German or Dutch. When I told him I was American, he shrugged and replied, “I don’t fucking care, come sit with us.”

We did, and a few beers later we were confusedly following him at his command to what we thought was his home. It wasn’t, though—it was the apartment of a friend of his, who unbeknownst to us had just the week before demanded that he stop bringing random punks back to her place when she wasn’t home. She wasn’t home when we arrived, and when she did come home she made no sign at all that she even noticed we were there. She ate dinner without speaking, then drank an espresso before finally looking at us and asking, “so. Who the fuck are you?”

She and I have been friends every since, and the three of us sat together in a bar we all once hung out in, amused at what it had become. I think she and my husband talked with each other more than I talked with them, and it felt brilliant and beautiful to watch them become as quick of friends and Duf and I had become.

Day Fourteen: Home

And now we are home. There are many more stories that I could write about it, and maybe I will one day, but for now this is all the words I have for it all.

Home feels new, probably because we are new. Just as all the trees around our house feel like different trees, we’re different, too. We’re not the same people who left, just as no one is ever the same person arriving again at the place from which they started.

The equation for adding series of ascending numbers is actually super easy and feels self-evident once you know it. You multiply the number pairs in an even set by the total of the sum of the highest and lowest number, and if it’s an odd set, the highest number is sum you use and you count it also as a pair. So, for 55, it’s 55 times 28 (1540); and for 45 its 45 times 22 (1035), thus 2575. Had I not reset the tunnel-kiss count, he’d have gotten a total of 5050 kisses for tunnels alone.