"Born This Way?"

Sex, sexuality, and the "problem" of the body

A point I make often in the courses on Marx that I instruct, as well as my newer Being Pagan course, is that the birth of capitalism changed our relationship to the body. This, of course, isn’t my idea. Both Foucault and Federici have outlined this problem, though in importantly different ways.

Michel Foucault wrote of the political and social construction of the body through the modern mechanisms of control and discipline and the body’s subsequent medicalisation. But the weakness of Foucault, which Federici quickly noticed, was that in the end the body is only discursive subject or social construction in his writings.

Put an easier way, one can read Foucault and leave with the belief that the body doesn’t really exist except as a idea in our head. That is, the body is a “construct,” just like gender or race.

The problem is of course that we are bodies. No matter how much our ideas about the body might be changed through social, economic, and political processes, at the end of the day the body is still there. We eat, sleep, shit, fuck, breathe, and die no matter what we actually believe about ourselves or what ideology tells us we are doing.

On the other hand, Silvia Federici, while acknowledging the processes that Foucault outlined throughout his work, re-inserted the body not as mere construction but as material reality, and then addressed the same historical changes through that lens.

A Very Brief History of the Body Under Capitalism

For those unfamiliar with either person’s work or the historical transition they analyzed, here is a brief description. Starting in the 1600’s, and especially occurring over the next 300 years, the way we thought about ourselves and the world radically changed.

We’re normally taught in schools about the way political society changed (from monarchies to republics and democratic nation-states, for example) or the changes in economic production (the end of feudalism and the birth of industrial capitalism). And some discussion is usually given to the so-called Enlightenment and how that changed our view of science, religion, and the rights of man.

Foucault, however, convincingly shows that this very same period saw radical changes in the way we thought of ourselves and others as humans. Most famously, this occurred through state mechanisms of control: the rise of modern institutions like the prison, the school, and the hospital, for instance, as well as the explosion of new laws directed at controlling certain behaviours and new sciences whose goals were understanding why those behaviors existed.

This period saw many things we now call pseudoscience, but this is actually a false way of describing them. No matter whether or not we now accept such practices as “true” science, they were scientific pursuits nevertheless.

Consider all the terrifying scientific activities involving the measuring and classification of people according to the new conception of race, or the horrifying treatment of women (including subjecting them to medical experiments, electroshock, and lobotomies). These are things now which we look back on and dismiss as pseudoscience, that is “fake” science. But they are all part of the scientific tradition nevertheless, and even the many Nazi experiments on humans still inform science today.

We now tend to think of science as a sacred and “good” process, and disavow all the earlier manifestations of science that were “not good” as being false science. We’re only able to do this through a trick of the mind and an idea that arose through this very same period: progress. The idea of progress lets us disavow everything in the history of science as being merely from a less unenlightened time, while still holding on to everything that history created (science itself) as an enlightened and pure version of the same thing.

So, it was Foucault who showed us all this, though I need to point out that this is rarely what Foucault is ever remembered for. Instead, his ideas on the social construction of the body and sex are what are most cited, because they form the basis for the later work of Judith Butler and other theorists who have shaped how we see gender and sex now.

Federici looked at that very same time period and those transitions and re-inserted the body as an actual thing, rather than just a socially-produced idea. With that radical framework (which isn’t really all that radical when you think about it), she was then able to show how all these social and political changes functioned as a war against bodies themselves.

Consider a woman strapped down to a bed, surrounded by male doctors and observers in an operating theatre as her uterus is being examined. She is not just a socially-constructed subject but rather an actual human body. Thus, the violation occurring to her is a violation against her as a body.

By looking at the body itself, Federici’s work reveals that the changing views about bodies were part of a drive towards the control of bodies themselves. This is particularly profound during the birth of industrial capitalism, where human bodies were seen more and more like machines and less like organic reality.

The capitalists needed to change our understanding of the body in order to make humans fit into their new systems of production. As Federici says in her brilliant short essay, “In Praise of the Dancing Body:”

Mechanization—the turning of the body, male and female, into a machine—has been one of capitalism’s most relentless pursuits. Animals too are turned into machines, so that sows can double their littler, chicken can produce uninterrupted flows of eggs, while unproductive ones are grounded like stones, and calves can never stand on their feet before being brought to the slaughter house.

I cannot here evoke all the ways in which the mechanization of body has occurred. Enough to say that the techniques of capture and domination have changed depending on the dominant labor regime and the machines that have been the model for the body.

Thus we find that in the 16 and 17th centuries (the time of manufacture) the body was imagined and disciplined according to the model of simple machines, like the pump and the lever. This was the regime that culminated in Taylorism, time-motion study, where every motion was calculated and all our energies were channeled to the task. Resistance here was imagined in the form of inertia, with the body pictured as a dumb animal, a monster resistant to command.

So, from Foucault we get the processes which turned the body into social construct, but we do not actually get the body itself, nor the reasons for these changes. Fortunately, Federici gives that to us, but with implications that are extremely uncomfortable for our current understandings of ourselves, the body, and matters of race, gender, and sexuality.

Inverts and Uranians

To see just how uncomfortable these implications can be, let’s look at something personal to me.

As you maybe know, I’m a homosexual or a gay man. But what does that actually mean?

All of my sexual relations have been with other men, and I am a man. I do not sexually desire women, nor have I ever had any sexual relations with them. Thus, the modern term for this, which is the one I use as a shorthand if someone asks, is that I am gay or a homosexual.

Historically there have been other terms for this kind of arrangement of desires. In the early part of last century and much of the century before, there were two dominant words: invert and Uranian. Those were not just words, but rather concepts that came with a larger ideological framework.

An invert was thought to be someone who had an inverted sexual self, meaning that while they appeared externally male or female, their sexual self was the inverse of that externality. So, a gay man was an inverted woman and a lesbian woman was an inverted man. Therefore, someone like me, who looks for all purposes like a man would be secretly and invisibly a woman because I desire men.

The other word, Uranian, has a much more interesting history. It was born out of an occult-drenched movement in Germany (centered primarily in Berlin) and first formulated by Karl Heinrich Ulrichs.

The term Uranian was derived from Greek lore about Aphrodite, who is spoken of as having had two different births. In the most well-known account, Aphrodite was the daughter of Zeus and a titaness named Dione (sometimes thought to be Diana). However, there is a second story, one in which Aphrodite is born not from a female at all, but rather from the semen of a male god, Uranus.

Ulrichs and others took up this term as a historical and spiritual container for their experiences of sexual desire. Along with this term came also the idea that they were somehow a different class of men, born spiritually into a different divine order and thus not really normal men but a kind of double man.

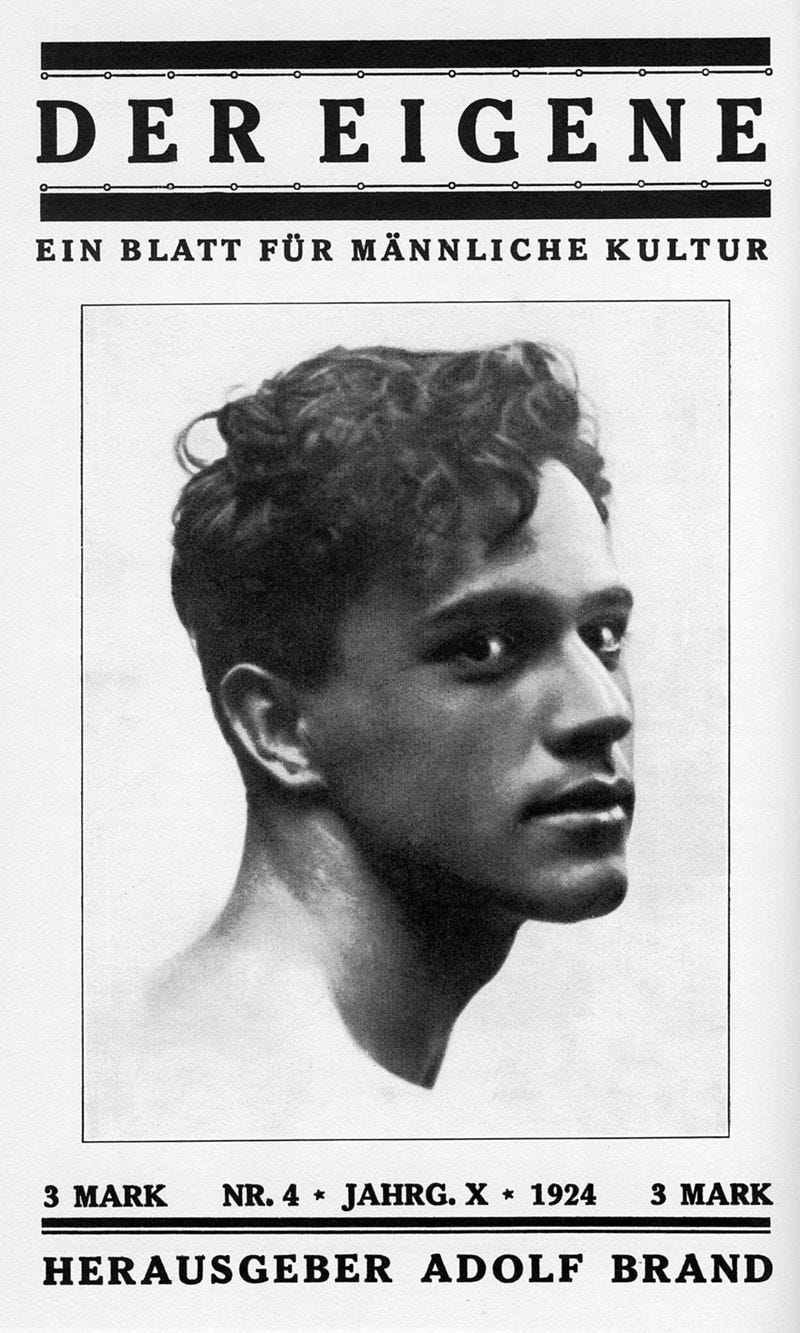

Half a century of writing then explored this idea, especially in Adolf Brand’s Der Eigene, the world’s first “gay” journal. That journal, whose title is a reference to Max Stirner’s philosophy (Der Eigene means “the unique”), ran for several decades before being seized and shut down by the Nazis. Der Eigene contained poetry, fiction, anarchist philosophy, and occult theory all aimed towards understanding what it meant to be what we now call “gay” or “homosexual.”

The German movement’s conception of their desire and its relationship to maleness was radically different from the way it was framed within inversion. While in inversion a man who desires a man is thought to be internally female, for the movement represented by Der Eigene, a man who desired other men was actually more of a man than other men. That is, they were so male that they only desired other males, and this was because they were of a spiritual line of men who sprung from the semen of a god, rather than from the womb of a goddess.

This framework may seem a bit ridiculous, but there is extensive historical precedent for this kind of conception around male-male desire. For both the Romans and Greeks, only upper class men were thought of as having the right to “only” have sex with other men. The focus here was on penetration. Just as in many Middle Eastern societies today (for instance, Turkey) and also in old Germanic societies, a man could penetrate another man without ever having been thought of doing anything wrong or unnatural. Being penetrated was a different matter: it would be shameful for a dominant man to be the receptive sexual partner, whereas it was not shameful for a man with less power (whether that power was related to age or class) to be penetrated.

The Uranian and the invert frameworks for same-sex desire were both born during the same period, but they had different actors and political ideologies behind them. The historical and spiritual framework of the Uranian and Der Eigene was heavily steeped in anarchist and occult ideas, and it was formulated by the men for whom these titles were developed to apply. In modern terms, we could say it was an organic “gay movement,” rather than a scientific or state formulation.

On the other hand, the concept of inversion was fully a scientific invention meant to define, classify, and treat an aberration or disorder. Invert was an externally-created label, one meant to be applied to others as a diagnosis.

The Body as Natural Limit

While neither framework is overtly in use, we should note which of them has continued on in new scientific and theoretical formulations. Inversion is the ancestor of all our current ways of thinking about both same-sex desire and transgender people.

To see how this is the case, let’s start with the modern notion that gays are “born this way.” The problem with this framework is the same problem that both Foucault and Federici point to: the medicalisation of the body. The search for the “gay gene” or other biological causes of homosexual desire is part of the same scientific project which turned the body into a social construct, externalising it from the human rather than seeing it as the material grounds for being human.

To put it another way, “born this way” contains an insistence that sexuality needs a scientific justification in order to be accepted as something humans can be. We therefore needed to prove that homosexuality is a problem of genetic code or an aberration in the brain (for example the many studies that attempted to prove that gay men had “female” brains, which is just the same theory of inversion from the 19th century with new measuring tools) in order for homosexuals to be accepted within the social order.

This has consequences for how we look at gender as well. Trans and non-binary people are currently in a position where they can only define their experiences through the scientific inversion model, that there is something internally different from their externality. Thus, to justify being born sexed in one way but desiring to express yourself in a way that is seen only exclusive to the other sex, there is only the inversion framework to guide you.

For Foucault and the gender theorists who use his work, this isn’t a problem at all and is anyway how is must be, because for them the body itself is a social construct and discursive subject.

In Federici, however, we see another option, the same option that the German Uranians and the writers of Der Eigene explored.

Something that is often misunderstood in Federici’s work is the concept of the body as a natural limit. This has been taken by some to mean that there are limits to the body and that we should all accept a kind of natural determinism, but this is hardly at all what she means. Instead, the body is a natural limit to the full exploitation of humans, our complete and total conversion into interchangeable machine parts for the capitalist order. From “In Praise of the Dancing Body” again:

By the body as a ‘natural limit’ I refer to the structure of needs and desires created in us not only by our conscious decisions or collective practices, but by millions of years of material evolution: the need for the sun, for the blue sky and the green of trees, for the smell of the woods and the oceans, the need for touching, smelling, sleeping, making love.

This accumulated structure of needs and desires, that for thousands of years have been the condition of our social reproduction, has put limits to our exploitation and is something that capitalism has incessantly struggled to overcome.

For the capitalists, and more broadly for the entire ideological framework of modern science and politics, the body is the “bone in the throat,” the physical thing that constantly chokes up the efforts to completely turn humans into mere social constructs and interchangeable workers.

The body as natural limit includes our desiring, whether that is desiring for people who are of the same sex as us or the other sex. Sex itself, both the act and the physical reality, is a primary site of contention and struggle. Sexual difference makes it impossible for humans to be fully interchangeable as laborers, and though sexual desire is relentlessly commodified (the way sex is used to sell us products, for instance, or the way gayness became culturally constructed to mean that people like me love to shop and adopt every new fashion trend1), it still resists scientific and political control.

Because we have inherited the inversion framework rather than the spiritual one, we are constantly trapped in relentless conflict about what sex and sexuality mean. That is at least partially because the scientific framework is constantly shifting, but also because the political frameworks of modern nations inform what narratives we use.

“Born this way” became a dominant narrative because it was useful in fighting laws which made same-sex acts illegal. If people were born gay, than they had no choice but to have sex with people of the same sex; therefore, making something they had no choice over illegal was an untenable political position.

The problem is that this completely removes from us our sexual agency. I absolutely have choice about who I have sex with. I could absolutely choose to have sex with a woman, but because I have absolutely no interest in doing so and wouldn’t find it very satisfying, I choose not to. It is the same with my choices about which men I have such relations with. I choose certain men and do not choose other men, not because of some inherent biological “problem” or social construction, but because that is how I choose to manifest my desire.

From Two is Born Three…

This way of thinking about sex and sexuality is much closer to the Uranian/Der Eigene current, which is itself much closer to traditional animist and indigenous ways of thinking about sex and sexuality. Sex in those cultures was absolutely a polarity, but it was not the only polarity. That’s why there have been so many tertiary “genders”2 in such societies, often a third, fourth, and even fifth group.

Those tertiary forms were different from our modern capitalist conception of trans, non-binary, and homosexual in that they were not attempts to re-inscribe differences back into the primary categories. What that means is that, for a person who was female but whose desires or expressions aligned with tradition maleness, they were a third kind of person, rather than “actually men” or “internally men.” The same went the other way around, and for other variations.

Here though we need to understand that such societies spiritualized these categories. Or better said, there was a sacred aspect to such variations, and those to whom those categories applied had culturally vital roles. This is why we see so many spiritual leaders in indigenous animist cultures described as being both man and woman, and also why so many pagan stories about gods involve sexual role-switching. Not just in the case of Aphrodite Urania (Aphrodite born from Uranus’s semen), but also in the stories of Dionysus being sewn up in Zeus’s thigh to be born from it, Arianrhod’s virgin birth of Dylan and Lleu, as well as Odin’s role switching in order to perform the traditionally female magic introduced to the Aesir by Freyj, seidr.

In fact, only the three monotheist cultures lack such lore and cultural roles for people who are not part of the male or female polarity. And since monotheism forms the cosmological basis for modern secular thinking, we need to also note that a culture that believes in only one god cannot accommodate a multiplicity of truths, either.

The matter of fundamentalist Islam as expressed currently in Iran is quite informative as to how the legacy of monotheism has also informed the capitalist order. In Iran, government approved gender re-assignment surgery and legal gender change has been in place since 1987, much earlier than any liberal democratic nation. This isn’t because Iran is a paradise of Butlerian gender theory, but rather because of a fatwa issued by religious leaders proclaiming that homosexuals who became women were not violating Islamic teachings. In fact, it was the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the leader of the Iranian revolution which instituted strict Islamic law there, who issued the fatwa.

Thus, the only way to legally practice homosexuality in Iran is get surgery to make your body more in line with the opposite sex of the people you desire. Put another way, the person who desires someone of the same sex is “trapped in the wrong body,” and therefore the body must be changed in order to conform with the natural order of things as seen in Islamic law.

This has an uncomfortable parallel to some of the scientific and political constructions for transgender people in the west, particularly in the sense that there is something “wrong” with the body or the body itself is “wrong”. This is ultimately the inversion framework: there is something different about the internal body that does not match up with its external features.

Again, we need to contrast this framework with the animist ways of thinking of such things. In an animist framework, there is no such thing as being in the wrong body. If a person is sexed as male but feels themselves more aligned with traditional female expressions, than this is a manifestation of their unique existence as body.

That is, it isn’t a problem to be solved, but a fact to be celebrated and a destiny to be fulfilled. They are a third kind of person, or a fourth, or a fifth, just as the men who wrote for Der Eigene saw themselves as a different kind of man rather than internally or “actually” women or just like other men.

These other kinds of bodies are also part of Federici’s “body as natural limit,” because they resist the capitalist need to classify bodies into discrete identities in order to exploit their labor more efficiently. That is, they are the body and its desires re-asserting itself as a physical reality, rather than a mere social construct or a medical problem to be solved.

Here we can finally see the mess that we are in with gender discussions based only on Foucault’s understanding. They all replicate the scientific inversion framework, that there is an internal feeling that can be completely separate from the body itself. Thus, if you feel yourself to be a man or a woman, and if the body you are “trapped in” doesn’t reflect this internal reality, than your body must change to conform to this internal reality.

The problem is that this “internal reality”—rather than the body—is the true site of political and social construction. The body isn’t a social construct, but rather the way we see the body as external to us is what is constructed. “Internal reality,” the ideas and beliefs about ourselves, are what the capitalists tried to change in order to alienate us from our bodily existence to therefore exploit us easier.

“Internal reality” is what advertisers target and manipulate. It’s how they sell us products we don’t need, by telling us that our bodies are too fat, too thin, to old, too short, too tall, too ugly, too hairy, too smelly, and too unattractive, too masculine, too feminine, or not masculine or feminine enough.3 Here we should remember how much of such advertising is based on sex, on telling us we will have more of it or become more desirable to others if we change something about ourselves through consuming their products.

Consider also how so many products are sold to us through manipulating our sense of social alienation. Coke is marketed through ideas and feelings of friendship, for example, just as a smartphones or other tech gadgets are marketed through sentiments about connection. Yet Coke doesn’t actually make you friends, and smartphones only deepen your alienation from the world around you.

Friendship and connection are both aspects of the desiring body, just as sex is an aspect of that same body. Yet through capitalism, we have come to see these as “internal” needs that can be shaped or replaced, rather than bodily needs which represent limits to how much we can be exploited. That is, the body needs friendship and connection and sex, and these are all things which remind us we are not machines or consumers, but flesh and blood beings who cannot be fully absorbed into the political order.

What does this all mean for sexually variant people now? First of all, we should notice how many of the arguments on all sides come down to trying to fit everyone into one of two categories, rather than creating new categories.

This is a particular weakness in many of the discussions about non-binarism: the binary itself is a computer model, part of the machine thinking integral to capitalist modernity. However, to merely say that someone is non-binary is to say nothing really at all, since male and female are not an on/off bit of computer code but rather two kinds of bodily existences that do not exclude others.

Put another way, two anticipates the existence of a third, which is a key truth in alchemy, in druidic thought, and even in the Marxist dialectic. This is what ancient societies understood but what we moderns refuse to comprehend: variance and difference are core truths of the body itself. While most bodies will fit into one category or an other, some bodies will vary from those categories and that variation is important. Not only is it important, but it is vital to the cultural life of a people and thus sacred.

So an obvious conclusion then is that, instead of trying to force every person into male or female, or on the other hand trying to redefine male or female to accommodate those who vary from that polarity, we could do the same thing those ancient cultures did but which monotheist cultures could never allow: we can recognize more than two types of bodies.

What that could look like, put plainly: there are women who do women thing and men who do men things. Women who do men things, men who do women things. Men who desire men, women who desire women. Men and women who desire both men and women. And each sort of man or woman is a different sort from the first two.4

Rather than the scientific inversion framework, we can look to the spiritual and anarchist tradition of Der Eigene, seeing each kind of person as unique, having unique roles and importance in the cultural life of people that do not alter the roles or meaning of the others.

Of course, that would require our societies themselves to change, a transformation that would also require an end to capitalism. This is much harder than enforcing the correct use of pronouns, changing educational policies, and creating anti-discrimination laws against which people are increasingly rebelling. Legislating and enforcing the inversion framework only exacerbates these conflicts, but this is the only solution the capitalist order can countenance.

So any such transformation would have to come from elsewhere. Once I believed the left might be able to bring about that sort of change, but as long as the left is so hostile to the concept of the sacred and so desperate to prove itself the true inheritors of “progress,” this will never happen.

But anyway, what is needed here are not political changes, but rather a de-politicisation of the body and of our desires. What is needed is a reclamation of the body as a natural limit against the modern regime of control, something that neither the scientists, nor the politicians, nor the gender theorists, nor the capitalists can ever truly define.

Like this essay? Please consider commenting and sharing it! Thanks!

I don’t.

Gender isn’t really the right word but I will need to explain this in a different essay.

The concerns that advertising is perpetuating a constructed idea of what a real man and real woman are, and that this may have an adverse affect on the way younger people—especially young women—see their bodies are therefore quite valid.

The very contentious statement by African feminist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie that “trans women are trans women” is therefore quite radical and also quite animist. That is, rather than trans women being “really men” or trans women being “really women,” she offered an African animist view: trans women are an entirely different and unique (in the Max Stirner sense of unique) category that cannot be reduced to either man or woman.

Yes! Thank you, I really resonate with this. I remember years ago a friend agonizing over whether they were a "man" or a "woman," and feeling so alienated and even ashamed. I told them that I thought they were unique and beautiful and exotic, actually a wonderful thing unlike anyone else. I don't know if that was the right or wrong thing to say, but I do know that it felt so limiting to have to force someone to fit into the category of either "man" or "woman." I think it's very unfortunate that the trans activists seem to have bought into this so fully. It would seem to be so much more liberating to break free of all the strictures. I used to think we were all on some sort of continuum, but now I wonder whether we're just randomly spectacular in our own unique ways.

"-but as long as the left is so hostile to the concept of the sacred and so desperate to prove itself the true inheritors of “progress,” this will never happen."

That has the ring of truth.