Currents of the Unseen

Greece travel journal, part one

In just a few days, I’ll be waking early in this very large house in a very small village and making my way to an airport. It will be my first plane in years, I guess almost six years now, and I’m going somewhere I’ve never been.

Whenever I’ve traveled somewhere for more than a few days, and especially to places of deep significance, I’ve written public travel journals. I’ll be doing the same thing this time.

Previous journals have been collected in two of my published books. In Your Face is a Forest, “Wanderings” recounts my first pilgrimage to European sacred sites, compelled by strange dreams and chased by even stranger presences. A Kindness of Ravens contains the second long series of journals. That journey was initiated by a rather unlikely (but unsurprising, in retrospect) summons to the passage tomb of Newgrange for Winter Solstice.

Last year, I published “Moons of Blood and Honey” and “Arriving Where We Started,” two journals from a road trip with my husband to Croatia and back. The occasion was both our honeymoon and also the celebration of the completed first draft of Here Be Monsters, my soon-to-be-released book on identity politics and the left.

Currently, I’m reading heavily for a new book, and this trip, though officially unrelated, is rather fortuitous. I’m traveling to Greece, specifically to Patmos, for (and because of the generosity of) Black Elephant. The occasion is an event called Meta+Physics, and I’ll be there along with some people readers likely already know (Dougald Hine, Martin Shaw, Elizabeth Oldfield, Thordis Elva) and many others.

Patmos, as you maybe also know, is where a really awful human named John wrote the Book of Revelation, where he condemned everyone he didn’t like (especially fornicating idolators like myself, and probably many of you) to a burning lake of fire for eternity. Before him, though, it was an island sacred to both Artemis and Selene, the latter of whom was said to have raised it from the ocean at the former’s request.

Besides being there, I’ll also do some traveling in Athens and visit some ancient pagan places I’ve long needed to be in.

30-31 May

It snuck up on me. I’d forgotten this feeling as it’s been so damn long. Just before you travel, something starts to inhabit you. Call it the spirit of the journey if you like, or if you’d rather not call anything a spirit, call it a kind of current that sweeps you up just before you leave. You don’t have to summon it, and I’m not sure summoning it would even work. It’s just there, pulling you away from where you are towards somewhere you soon will be.

It feels a bit like Walter Benjamin’s description of Paul Klee’s painting, “Angelus Novus,” in his On The Concept of History:

…a storm is blowing in from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such a violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward.

The last few weeks, or really the last few months — since Imbolc, or at least Buergbrennan — my life’s been a bit strange. A bit different, or maybe more accurately intensely different. Strange, sometimes alien, sometimes unrecognizable, sometimes confusing. Really, ever since I started reading for this next book.

I don’t actually understand these differences yet, which is why I’m writing about it. Writing’s always been the way I unravel the knots of meaning in my life, and how I use those threads to reweave new meaning. Journal-writing, especially, has always been the most helpful for getting reflected glimpses of myself, but for reasons I don’t quite understand, I find myself too often the last few years staring at page after page of blankness.

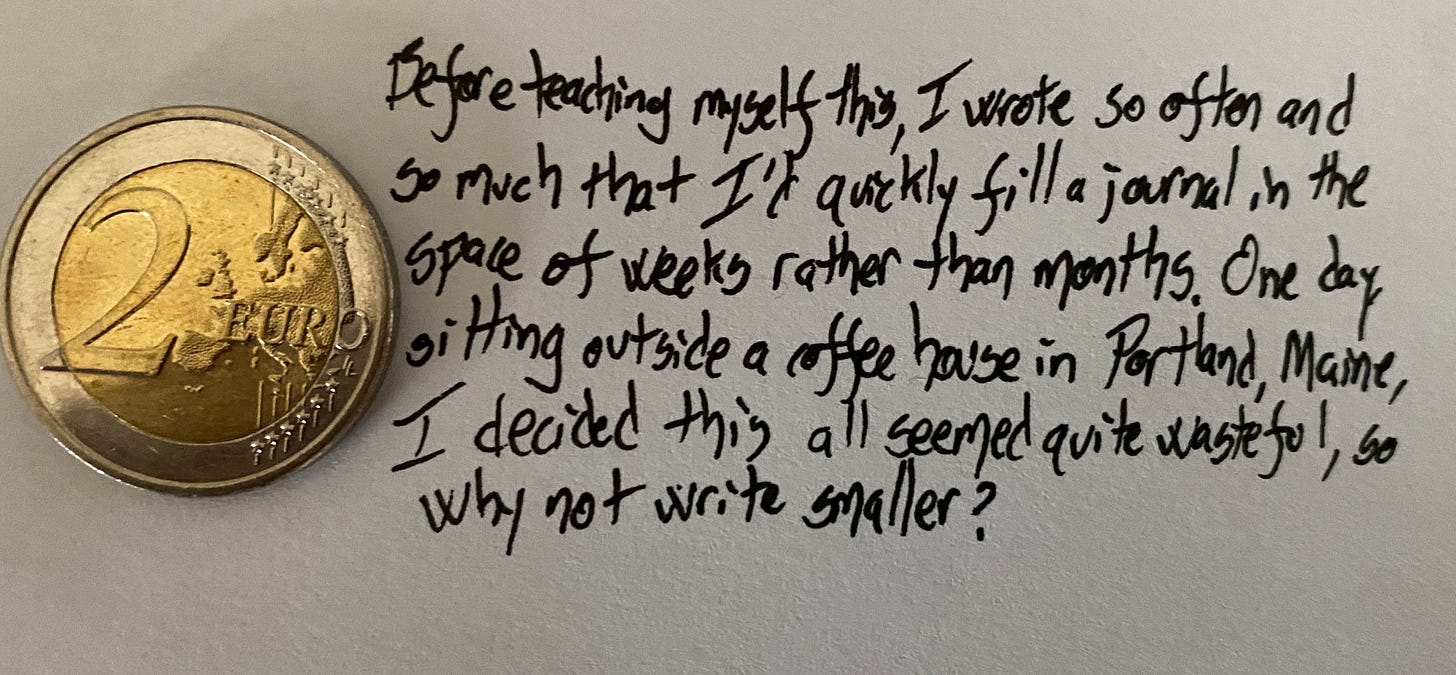

Perhaps it’s because much of my adolescence, all of my twenties, and much of my thirties, I wrote primarily only to myself. I’ve a very peculiar and minuscule handwriting, a skill I purposefully trained myself to acquire in order to save paper. Before teaching myself this, I wrote so often and so much that I’d quickly fill a journal in the space of weeks rather than months. One day, sitting outside a coffeeshop in Portland, Maine, I decided this all seemed quite wasteful, so why not write smaller?

There’s become a problem with writing so small, though, which is that I cannot read my own writing without glasses any longer. I started doing this 26 years ago, and back then my eyesight was more than perfect. I’ve always been very farsighted. When I was younger, it was always a quite cool thing to be, since I could read writing or make out details from incredible distances which others couldn’t. I could also read up close just as well. Unfortunately, though nothing at all has changed in my ability to read very far away, anything within half a meter of my face is now a complete blur without glasses.

Since I thus far have resisted bifocal lenses, and probably always will, wearing my glasses to see things close by means I completely lose not just my extreme distance vision but also regular distance vision. In those times that I look up from a book or a screen and try to gaze out a window onto the ancient oak tree, I suddenly find myself feeling deeply claustrophobic. Everything far away disappears, and this feels quite terrifying.

I’m reminded that there’s always much more to sight than its “mere” physical reality. I mean by this something quite obvious when you think on it but completely unseen otherwise: our thoughts and our ways of perceiving the world are shaped by our over-reliance on sight.

I love — and deeply crave — wide open spaces, vast vistas, distant horizons, broad landscapes. Small rooms filled with people — even those I adore — make me quite nervous. A person suddenly so close to me that I cannot make out the details of their face immediately makes me recoil: not in fear so much as panicked urgency to push them away into my vision.

This shapes also the way I see the world, and notice the word I used for that, “see.” We tend to use visual metaphors for knowledge, perception, and even sense because we primarily favor the visual over all other senses. You see what I mean, I see where you’re coming from, I saw that coming, I haven’t seen him in a long time, they’re seeing each other; statements which could just as easily have been made with the words “understand,” “sensed,” “been with,” or many others. We default to sight, though, and tend to forget we have other ways of knowing.

I’ve variously taken up practices to de-prioritize sight. Simple things, such as closing my eyes when listening to something, or making my way through rooms with my eyes closed. I do this especially during moments of intense body sensation, such as during certain weight-lifting sets in which I don’t need my sight to gauge distance or safety, or when a strong wind gusts past me outside, or during sex, or whenever I’m sitting in the sun.

This has also required de-prioritizing thought also, since so much of it derives from the visual. Especially, I’ve been trying to lean in heavily to the complete stupidity which floods the body after intense workouts. Also, I’ve been sunning myself stupid, an activity which is absolutely best done with eyes closed.

In fact, the longer I go through a day without any concrete, repeatable thought, the happier I find myself. The thoughts which come feel more like sensations, or like staring into a pleasant and familiar distance, taking in things so far away that they cannot present themselves as urgent.

Of course, there’s a downside to all this. Writing is a visual activity. Sure, I can type with my eyes closed, but that’s not really the problem. Writing is a visual communication, and it requires translating things unseen into things that can be seen. To go from active emptiness of thought to writing is often jolting. I’ve not yet found the balance here, and maybe never will.

1 June

I leave in five days, but only just today got around to actually looking at my travel details. I’ll be planing to Athens from Luxembourg, and then from Athens to Kos. From there, I’ll be on a ferry to Patmos, arriving at midnight.

I’d had this rather romantic notion of standing on the deck of the ferry in the Mediterranean, solitary, imagining what it will all be like to arrive and encounter the others. It was a silly thought, of course, since others going to the same place will be on that same ferry with me.

The last time I was on a ferry was a bit more than seven years ago, crossing the Irish Channel from Dublin to Holyhead for a trip to Beddgelert and Llyn Dinas. On that ferry I indeed stood on the deck alone, as it was really too cold and wet that winter morning for anyone else to be as silly as I was. A few smokers joined me there briefly. They tried in vain to light cigarettes, cursed a few times in that really quite forward Irish way, and then left me to my solitude.

I whiled most of my time outside in the cold rain, despite having initially decided to write. I was a bit blocked, literally, in that other endeavour. I’d tried to use the ferry’s on-board wireless internet (at a cost of ten euro, if I remember correctly) to access the wordpress site where I wrote. I received a message immediately after each attempt stating that the site I was trying to access was blocked.

The reason? “Religiously offensive or abusive content.” Later I learned that the word “pagan” was one of the key words contained in the database of offensive words the Irish ferry company’s internet filter used, which still amuses me.

I’m ahead of myself now, and also behind myself. I’m not on a ferry yet, and I’m not on that earlier ferry. I’m here, typing, remembering the past and future at the same time while trying to let my legs rest.

Today, I did what I suspect will probably be my last gym session before the trip, and it’s such a weird thing to me that I actually don’t like this idea. I mentioned offhandedly to my trainer that I’d found a gym on Patmos that sells day passes, and another one in the neighborhood of the place I’ll be staying in Athens, and she laughed, saying, “you know, it’s okay to not work out sometimes.”

I like that I need to be reminded of this, even though I’m not sure I really feel this to be true. My gym work since the beginning of February has been perhaps one of the only things that makes any real sense to me. It’s how I play, and it’s also a bit (I know this is cliché) my temple or church. I feel closest to the gods there than anywhere else, even closer than I do in forests, because it’s there I’m most myself and most body.

In an essay which absolutely merits your attention,

recently wrote about his experience at one of those American “fitness” chains, which are not really so much gyms but rather lifestyle centers. I’d never been to one in the US, but I’d heard before of the strange rules against people actually acting human:The ultimate taboo is extended to any action that might be interpreted as what they call “Gymtimidation”, which includes paradigmatically the behavior of the “Lunks”, creatures who groan when they lift weights, take large gulps from gallon-sized water bottles, and allow their barbells to crash to the floor when they have finished their reps. On the occasion of any such transgression, a “Lunk Alarm”, a rotating blue police light, will be set off — proving that there is at least one class of people, the Lunks themselves, to whom this vaunted freedom from “judgement” does not extend.

I’m one of those “lunks.” Though I try not to, especially after leg presses I sometimes let the weights crash at the end. While I don’t have a gallon jug of water (they don’t exist here), I’ve a 1.5 liter of water I chug to empty by halfway through my workout, refill it, and then chug it again. And good gods do I groan, and sweat rivers, and sometimes start to cry a little bit, especially on those aforementioned leg presses.

Fortunately, I’m not alone in this at my gym. It seems a few of us, women (mostly bull dykes, my favorite sort) and men (mostly German blue collar workers, again my favorite sort) have all figured out we can get away with being human if we all go at the same time. One insanely ripped dude with legs twice the size of mine smells like he actually works for a living, and yeah, he’s a champion grunter. He goes in early afternoon as I do, to not offend the easily-offended sorts. Those sorts, the ones who come later, are all the financial officers, lawyers, and other “professionals” who don’t want to hear noise or see anyone’s sweat and who sip water from bottles so small you can take them full through airport security. They’re not there to work out, they’re there to “stay fit,” which is Professional-Managerial Class speak for “not look poor.”

So I go with the dykes and the workers and also, on Thursdays, my 80 year-old mother-in-law. I cast occasional glances at her across the gym and smile, damn proud to be her son-in-law. Once in awhile, especially when I’m doing barbell squats, I notice in the mirror she’s watching me and smiling, too.

It’s funny that, when I started, the gym was a lot like a ferry for me. It was something to get me from one place to another. It’s not been that for a long time now, but rather a place I go to be myself. I’m still, at 46 years, trying to figure out precisely who that is. Or, rather, trying to discover who else that is besides who I already knew myself to be:

2 June

I’ll confess — Luxembourg has been a deeply lonely place for me.

I moved here just before almost all the governments of the world passed laws to prevent any kind of extra-economic social interactions. When I’d arrived, I was quite broken of soul, recovering from a deeply abusive relationship. Two months later, everything “locked down,” we all covered our faces, “kept distance,” and found ourselves acting as if every human outside our doors was a potential murderer.

I’d been invited to stay with the man who is now my husband, to ride out the apocalypse together. We’d only just met, and it was all a bit fast, but it sounded like an adventure regardless and I anyway liked him. It was indeed an adventure: I rode my sister’s bike for four hours to his home a few days after it became illegal for me to have done so. I took forest paths and alleys to avoid police blockades and overzealous citizens.

He still went to work during the confinements, meaning I had hours and hours alone in a house I didn’t yet know in a small village to which I was deeply strange. Everything was deeply quiet back then, eerily so. Almost no cars passed the house, such that, were it not for phones and internet, I might have suspected almost the entire world had died off in plague.

By the time things opened up again, and the much later time when we were allowed to have faces again, almost two years had passed. It really might as well have been a decade. In my 20’s, I had fantasized many times about becoming a monk or a hermit; the pandemic fulfilled that wish long after I understood I no longer wished it. The longer the lockdown lasted, the more I realised my youthful fantasy had been really quite ridiculous.

Trying to make friends in your 40’s is hardly easy. Trying to make friends as an immigrant is just as difficult. Add to those both the absurd fear of other humans and contagion beaten into us through constant propaganda and years of people forgetting even how to communicate without a screen, and you’ve got a very isolating situation.

I’ve two friends here. Sometimes I say “only,” but only at times I’m feeling a bit tragic. Two is actually quite good considering all else. And sure, I like and am liked by others, but those two are the only ones who might call me up because they need to talk and would like to be called up when I need to, too.

I was with one of them this evening. We’ve been friends since soon after I arrived. We’d met for coffee a few weeks before covid hit, excitedly promising to see each other again quite soon, and then soon found we weren’t “allowed” to do so. Despite that, we did finally see each other again, and then again, and found to our delight that we’d become friends.

Our original plan had been to attend an opening of a new bistro to which he’d been invited. The other guests already there were what we call “A” gays, so we left without really even arriving. “A” gays are the sort you see depicted on television and films, the professional high-income Ibiza-going loft-owning guys, the ones with hair transplants and botoxed eyes at 35. They're awful to be around, and vapid as hell, and precisely the sorts who feel deeply offended when someone grunts at the gym.

When I was younger and more punk, I often delighted in taunting them, but I’m old enough now to know it’s best to leave them be.

Instead we went to the same café where we first met, talking of the things of which we usually talk. Life stuff, and work stuff, and relationship stuff. Sex always comes up, as he and his soon-to-be-husband are champion sluts and I adore his stories. He’d mentioned his rather active time at a gay sauna in Germany, offhandedly mentioning he’d stopped for fast food afterwards. “Wait, really?” I asked, genuinely shocked. It took me some time to notice the delicious humor: I’d not blinked an eye at the amount of men he’d been inside that day, but I found it unconscionable that he’d then also been inside a McDonald’s.

Laughing at this felt like recalling myself. It’s been far too long since I’ve been that specific “me,” a me I’ve found myself unconsciously suppressing since coming to Europe. Had I moved to Germany rather than first to France and later to Luxembourg, perhaps such a thing might never have happened. Germans at least figured out quite quickly that sexual repression leads to very dark places, and making sex a verboten topic turns it into something much more powerful than it should be.

But there is something deeper here. Since coming to Europe and especially to Luxembourg, I’ve noticed I regularly diminish parts of myself out of fear of giving offense. I’m not sure this is really a new thing, however. In fact, I think I’ve done this my entire life, and maybe only noticed it now because I’m no longer in the cultural environment in which that habit first developed.

I’ve found myself returning repeatedly to a question I’ve not yet been able to answer: why do I do this? And especially, why do I always ask permission for things I don’t need permission for? The more I consider this question, the more a subtle and dormant anger seems to well up in my soul. I think that I do actually know its answer and its cause, but looking at the truth too directly is quite enraging.

I’ve prided myself on the decades of work I’ve done — and yes, it’s taken decades — to exorcise all the soul-crushing habits and discipline which my early years as a Christian wrought in me. The subservience falsely called “humility,” the constant groveling at the feet of a vengeful sky father, the assurances that all suffering and tragedy is ultimately merely a “test” to show faith and obedience, and all the other ways that the “holy” spirit of the one-god molds the true believer: that’s why I still ask permission, why I am afraid to take up “too much” space in the world, and why being anything more than what I think I am “allowed” to be feels like some great crime for which one day I will certain be punished.

It’s all what Nietzsche called the slave morality, the willful abdication of agency to others. He saw it as a core feature of Judeo-Christian religious traditions, which isn’t too hard to see once we remember the most common title for the Christian god is “Lord.” And while I no longer interact with any deity who’d expect such a feudal address, vestiges of that posture of subservience still remain in my life.

Pondering this in retrospect makes the chance meeting I had at that café with my friend seem much more profound. During a lull in our lewd banter in the warm evening, I noticed the title of the well-worn book being read by the man at the table next to us.

“Are you really reading Trotsky, mate?” I asked.

The man nodded, smiling. “Yeah, do you know him?”

A fellow American leftist — and as it soon turned out a fellow Appalachian — had been deep into a communist text while smiling affably at our discussion. Suddenly we were talking about Adolph Reed and Mark Fisher, about those still insist class consciousness matters and my upcoming book. This was all why leftism made any sense to me in the first place: a return of agency.

I’ve written before on this, and also in my book, and I will again, but this has always been to me the greatest tragedy of “woke” politics or more accurately social justice identitarianism. It narrates every oppression and injustice as the fault of intangible and ultimately unfightable systems. Before that, to be a leftist was to believe that humans had the ability —and obligation — to determine their own circumstances and their own conditions. To labor is to create, something the capitalists don’t do. They merely harness and organize the labor of others towards their own ends and their own exclusive benefit.

As the three of us talked, yet another person, a table down, interrupted politely. She told us her grandmother was Lina Haag, a communist who’d survived the concentration camps. Haag had even managed to convince her camp guard to turn against the Gestapo. More wild than that, she’d also secured a meeting with Himmler, successfully convincing him to release her communist husband, as well.

That’s fucking agency.

Oh gods yeah I needed this today, thanks Rhyd, and good travels. Can't get to the gym today, feeling like my permission to take up space got revoked too many times by too many people, (and most often myself, obviously). Reading your piece, I feel like I just did leg press, although now perhaps slightly less stupid - feeling.

In my high school world history class we were assigned an oral report on an historical figure. For whatever reason, I chose Trotsky and actually located and read his autobiography. Embarrassingly, I had not noted that the reports were supposed to be 10 minutes long. The teacher stopped me at around 30 minutes. A few years later I think I encountered some Trotskyists in San Francisco when I was attending Women's Liberation meetings. There were also some Maoists. Both types hung around Women's movement events and tried to take over groups or lure women into proper leftist politics.

I am extremely nearsighted but adjusted well to bifocals. Going down stairs was most difficult.

Wonderful accounts of your earlier travels. Looking forward to Greece. Be careful on Patmos; in Classical times it was illegal to die or be born there.