Dis/Content

Regarding the supposed threat of AI

I’m currently laid up with what I’m pretty certain are quite severe allergies. Being laid up, unable to go to the gym or to garden, and not interested in reading more from the stack of books I’ve accumulated as research for my next book, I decided finally to look into the internet panic over ChatGPT, and of AI in general.

There are currently terrified proclamations that the end of the world has already come for certain genre writers, and will soon come for every writer in the world. The specific “crisis” is that authors publishing through Amazon’s Kindle Unlimited service suddenly noticed their revenue plummet on account of mass uploads of AI-generated digital titles, many of which were immediately catapulted to best-seller positions in their individual categories because of automated downloads through bots.

In other words, people are making a lot of money off of books on Amazon, without writing anything at all.

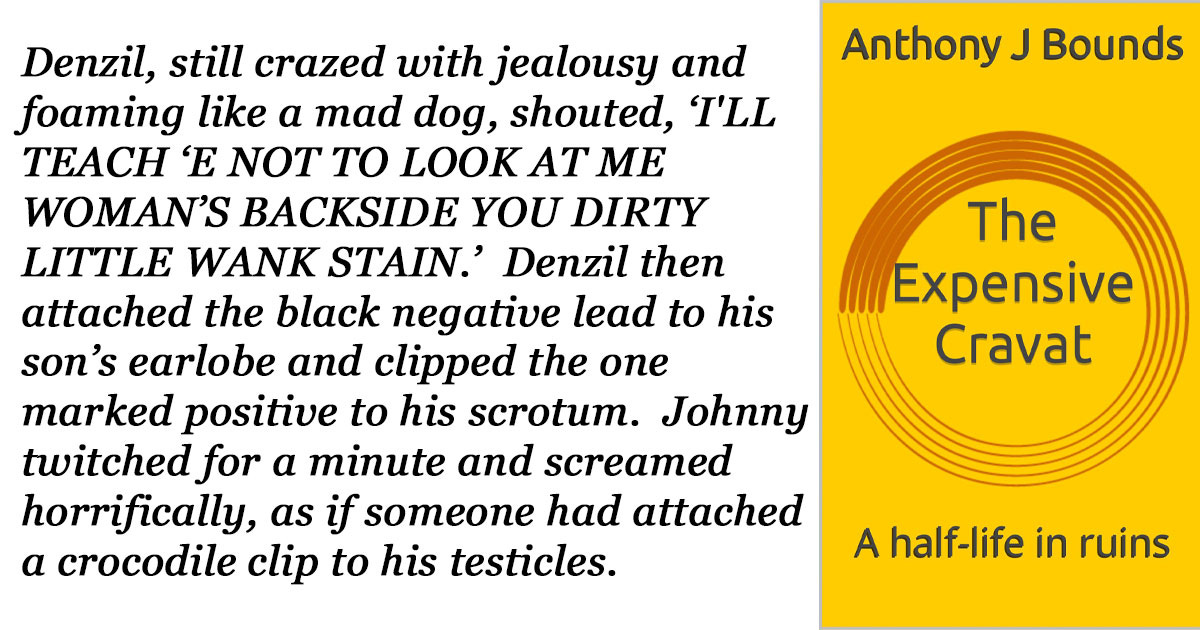

What tipped off authors to the true authorship of these books? Well, take for example one of these best-sellers:

Or there’s this compellingly-named “best-selling” book in military action fiction:

The reason these books are listed as “free” is because they are part of Kindle Unlimited. That’s a special monthly subscription service offered by Amazon that functions a bit like Netflix or other streaming services. Rather than buying each book you’d like to read, you pay a flat monthly fee and get access to each electronic book enrolled in the Kindle Unlimited service.

To clarify, though, this doesn’t mean “every” Kindle book. In fact, many Kindle editions (including my own, and also those published thus far by RITONA) are not included in Kindle Unlimited, and for very good reasons. First of all, to enroll your books, you must give Amazon exclusive digital distribution rights to your work, meaning digital versions (like .epubs or .pdfs) of your book cannot be sold by anyone else. And secondly, you agree to be paid not a flat price for your book, but rather a per-page rate, equal to about 2 cents for every 5 pages that a Kindle Unlimited user reads.

Now, there are a few reasons why authors might actually choose to publish with this agreement. Because there’s no real committment involved beyond the monthly subscription fee, a Kindle user might find themselves downloading books they wouldn’t normally download, and maybe even reading more this way. It’s a bit like what happens at an all-you-can-eat buffet: you’ve already paid the rate, so why not take a little bit of something you’d not usually order? And while there, why not get an extra helping even though you’re not going to finish it?

That last part is the most relevant for authors using Kindle Unlimited. Usually, a reader will at least read the first 10 pages of a book before deciding if it’s interesting enough to keep going. The author then gets paid 4 cents regardless of whether the reader actually keeps reading; if you’ve got a thousand people doing that in a month, you at least will make forty dollars.

Of course, forty dollars isn’t really a lot of money, especially if you spent a year writing a standard-length (90,000 word) novel. But, on the other hand, if you happened to write nine 10,000 word books, and the same number of readers just read the first ten pages of each, you’re looking at $360 a month. That’s not a bad side-income.

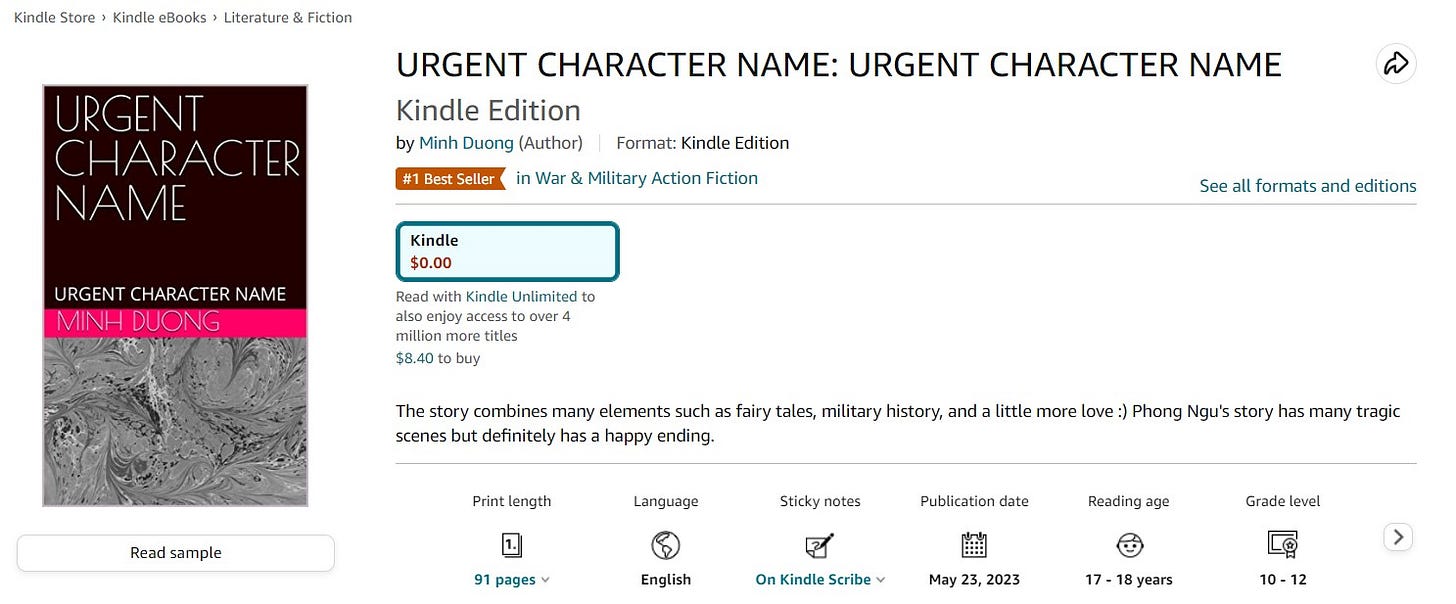

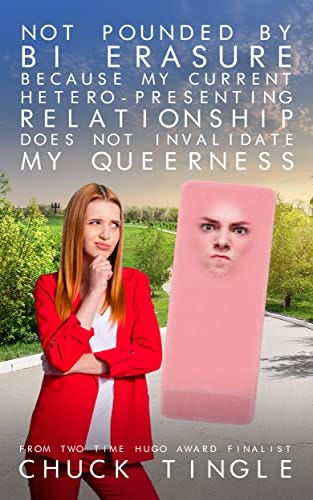

Some rather enterprising — but not necessarily good — writers figured out early on how to game the Kindle system even before Kindle Unlimited. Most notable of these was Chuck Tingle. He has published more than 350 very short (10,000 word) and cheap books with ridiculous titles, such as Pounded in the Butt By My Butt, Bisexual Mothman Mailman Makes a Special Delivery In Our Butts, and Space Raptor Butt Invasion, as well as quite a few titles referencing current “intersectional social justice” themes:

The author behind the pen name is reported to have made quite a bit of money from these books, and it’s a success many authors wouldn’t mind emulating. This kind of micro-fiction suddenly became the “thing” to do to get rich as an author, but there’s a limit to how much of this stuff anyone can really digest.

Kindle Unlimited was rolled out right about the time Tingle’s success really became quite renowned. Notably, though, Tingle isn’t actually available on Unlimited, because his notoriety is enough that he can make much more money by selling his books for cheap rather than by the page.

That’s an important part of the original reason why Kindle Unlimited became so popular with aspiring writers. You didn’t really need renown or even much publicity of your own to make a little money. All you really needed to do was get your book listed in the top 100 in a category for a little bit.

There were plenty of ways to do that. One of those was to encourage people on social media to download the book “for free.” Of course it wasn’t actually free, since you had to have a monthly subscription, but “free” sounds great regardless. With a spike in “free” downloads, your book went up in the bestseller list, which then got you more downloads.

You’ll notice that none of this has anything to do with writing a good book. In fact, many authors (starting with Chuck Tingle) noticed that crafty marketing and algorithm manipulation went much farther than honing your craft as a writer and writing a compelling book. In fact, you only needed to write something, and then convince people to download it, flip through a few pages, and you made some money.

A few authors made quite a bit of money through Kindle Unlimited, and many more have made modest amounts through it. Those who succeeded did so primarily through the same means I mentioned earlier: manipulating the algorithms to increase visibility of their works, rather than writing well. Yes, marketing is also a significant factor in a well-written book’s success, but it’s more of a factor for the success of poorly-written books than it is for great ones.

Before I directly discuss the ChatGPT issue, I should mention a little bit more about algorithms and their manipulation. Quite a few “traditional” publishers have been using algorithms to determine which subjects are currently in-demand. Then, they use this information to scout for and solicit manuscripts from potential authors on those subjects in order to capitalize on trending search terms. I’ve heard it said repeatedly that the major “new age/spirituality” publishers in the US have operated this way for quite some time now, and even some authors approached by them through these means have aired their complaints about it.

Also, of course, promotion of books is often reliant on social media. Authors, publishers, and publicists who were able to get to “Influencer” level on Instagram or otherwise collect very high follower counts (again, by manipulating algorithms through hashtag use) are able to get their book in front of many more potential readers.

In other words, algorithms have been part of publishing for several years now, and have become quite inescapable.

Now, on to AI-generated books. If you do a quick search on the internet for tutorials on how to use ChatGPT to write a book, you’ll quickly be inundated with video results. I’ve also been bombarded for at least the last half a year with advertisements for courses designed to teach how to “sell books you didn’t even write.”

The general gist of the tutorials is that you first use ChatGPT to identify a trending “niche” subject matter for your books. Then, you request it to list potential ideas for book titles and themes for one of those subjects, and then you request it to write text for a book with the subject, theme, and title.

Of course, you’ll end up with a lot of garbage at the beginning, which is why the tutorials then advise you to run the text through other “AI” systems to check for grammar, potential plagiarism, and even whether or not the text might be identified as AI-generated content. After a few hours of tweaking the text, you’ve now got a five thousand or ten thousand word “book” you can upload to Amazon Unlimited and enjoy your “passive” income.

When I finally decided to look into what they were suggesting, it suddenly struck me that it wasn’t really all that different from what many of the very same authors who are complaining about this problem were doing. Sure, they were physically typing out words rather than asking a chat bot to do it, but it’s not really true to say that they were actually writing “books.”

Instead, they were writing content.

What I mean by this might sound a bit judgmental, but I don’t really care. There’s really only three types of writing that we do in modern civilization. The first is the basic one we do everyday: writing notes on paper, texting to friends, writing reports for work, and all the other mundane things we write, conveying meaning and information to others or back to ourselves.

The second is what we can call “sacred” writing, meaning that it’s how we attempt to convey something more than mere information or signal. This is a much rarer kind of writing, because the sacred is also a much rarer kind of thing. This kind of writing doesn’t just include poetry and “great” prose, but also the love note you write to your wife, the handwritten letter to a distant friend, or what a law clerk types out when you are crafting your final will. It’s writing with importance (from Latin im-portare, something you “carry in”), rather than a scrawled set of signals.

The third bit is the newest sort, “content.” It’s what fills the space between a title and the end of the page, something to keep your attention moving in the direction the “content creator” would like it to move. It’s there to get you to click on something, or to click past it. You can see it best with recipe pages on the internet, paragraph after paragraph of writing you’re not even expected to read.1 It’s also all the “filler” articles in newspapers and the text on cheap shopping fliers, not actually meant to be read by anyone.

The first kind of writing requires little skill and functions best when it is concise: writing ponderous prose on a shopping list is not only inefficient, but it also makes the list difficult to use. The second sort of writing favors learned skill and thought, especially in word choice; whether it’s a novel or a love letter, saying things the best way becomes the overarching goal.

The third kind, though, cares nothing for concision nor word choice, only length. The more words written, the more content you’re paid for, whether that’s a newspaper circular, a political speech, or a Teen Vogue article.

Though there’s always been a market for drivel, it’s the internet that created this desperate need for “content” writing. In fact, it’s precisely because of the internet technology companies that we started lumping photographs, text, and audio into the singular term “content.”2 So, it’s no wonder that the same industry which began treating writing as mere filler would have also created a complex algorithm to generate that filler.

To put the matter of content in another perspective, consider my garden. It’s quite full at the moment: there’s a row of purple mustard, another of amaranth, two lines of onions, quite a few herbs (several basils — both Italian and Thai — oregano, chervil, five small laurel bushes, six rosemarys, six thymes, and some fennel), a few tomato plants, two peppers, two cucumbers, three red currant bushes, several bush beans and late peas, as well as some beets, carrots, and arugula.3 All of that is there because I intend to use it at some point, as I’ve already done for my lettuces and cilantro.

To this newer, techno-capitalist perspective, all those things are just “plants,” just the “content” in my garden. To such a mindset, it doesn’t really matter what’s in the garden at all, or even if any of it is edible, only that there’s something filling the emptiness.

This is also what has happened with writing, as well as photography, drawing, and music. It doesn’t matter whether any of its good, interesting, or meaningful: it’s all just content for the data servers, stuff to flash briefly across a screen before you scroll on to the next thing demanding your attention.

So, ChatGPT isn’t some new threat to human creativity, it’s just another front in the same war we’ve been losing for a long time now. It’s part of a top-down management view of human labor, the “revolutionizing of production” that the capitalist class has continuously implemented since the birth of the factory. In fact, since its data set is derived from “learning from” the previous products of human labor without consent (essentially, “primitive accumulation”), ChatGPT (and its image-creating equivalents4) is really just the further industrial exploitation of human value-creation.

This is all very similar to what we’ve seen in other expropriations of human labor and exchange. As I mentioned regarding Airbnb, a previous and informal subletting system had existed before capitalists noticed and found a way to harness it towards their own ends. That doesn’t mean the previous system was necessarily good or bad, and individuals in that system had already begun trying to profit-take, rather than just cover their costs. Like them, many of the authors complaining about this new exploitation of the Kindle Unlimited system were already exploiting it themselves, creating content for consumption, rather than books for reading.

So no, AI isn’t going to destroy writing careers, though it may destroy the careers of some “content creators” calling themselves writers. And books aren’t dying any time soon, nor will the human desire to write really great stories. What’s happening now is just capitalism doing what it’s always done, “disrupting” everything it touches, melting the solid into air, turning the sacred into the profane. But we can keep doing what is most sacred about us: making art and making meaning in the most skilled and beautiful ways we know how.

The reason for this is two-fold. First of all, having unique text before a recipe protects the website owner from copyright lawsuits, even if the recipe itself is identical. Secondly, the text is there because of third-party advertisements: it increases the amount of time you spend on the page and provides more space for the ads, meaning larger revenue potential.

I suspect it first started with the use of Adobe Photoshop and other digitial layout programs, which treat words and photographs as mere blocks to be moved around on a screen, though HTML and other coding languages did something similar before this.

This is not an exhaustive list.

For a great take on AI-generated art, see this piece by my colleague, Mirna Wabi-Sabi

Hi Rhyd -

I recommend taking a careful look at the much broader topic of risks associated with AI. One good place to start is with this presentation. But even this is just a small starting place for a vast topic.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xoVJKj8lcNQ&t=4s

I love the insight that “teaching” AI on the works of artists and writers is a form of primitive accumulation. I’ll admit to having paranoid spiritual concerns about the use of AI to generate art in the style of a particular artist. For example, creating “Beethoven” music by feeding AI Beethoven and having it create a “Beethoven” piece. I’m haven’t quite articulated my fear but I would describe such a thing as necromancy. Of course, I also have reservations about recorded music, especially from dead artists as well for similar reasons. Don’t get me wrong, I enjoy the hell out of listening to my favorite dead people sing but I wonder if there was some sort of natural limit implied in having to have a living person perform music composed by someone who is dead. That in some way that is healthy way of allowing the dead to speak, while I’m on the fence about listening to the dead soul sing