The first installment of this journal is here, and the second is here.

Sitting aft on a boat ferrying travellers across the Aegean Sea, the wind sweeping across my sunburned skin, I’m watching restless passengers as they search for distraction. They seem oddly uneasy, unsettled, unable to feel content with just sitting, staring, dreaming. A woman stands up from her seat inside, smokes, sits down, and then does it all again a few minutes later. Another woman stands against the rail, takes selfies, looks at her camera disappointed, and then goes back inside.

Why’s everyone so uneasy? I don’t understand, but I try to, and try to again. This trying suddenly feels wrong, too, and then I understand without trying to understand. There’s nothing unusual about their behavior, and it’s me, instead. I’m still in the time stream of Patmos, not quite ready to enter the time stream of others. I’m moving slower, thinking slower, writing slower. Words seem much less necessary, less interesting. “Island time,” I’ve heard this called, and maybe that’s what this is, but I’m pretty sure it’s something else, too.

7 June

Like all his other books, China Mieville’s novel Kraken is a rather bizarre and addicting read. Often his plots feel rather superfluous to the stories: as if afterthoughts, or maybe demands from an editor to “make this make sense, thanks.” Or, perhaps the plots are so bare by intention, frames raised slapdash, just enough structure to hold together all the rest.

The just-barely-sufficient frame of Kraken is that a giant squid has gone missing, and that squid is the god of a cult and key to their Apocalypse. The thing is, though, there are just as many apocalypses as there are religious cults in that world, and each of them eventually happens — but only for them. The impending end of the world for any particular religion becomes a minor matter of note in newspapers, announcements buried among other notices, the way auctions or rezoning requests are in our own. However, the giant squid’s sudden disappearance becomes a bit more newsworthy, since its cult’s apocalypse now threatens to become everyone else’s, too.

Patmos is the island of the Christians’ apocalypse, the place where their end of the world was revealed. One of the problems, however, is that — just like that great squid cult’s eschatological scenario — its most fervent believers insist it must slip from its limited, temporal relevance and become our collective end of the world. Even if we believe nothing of John of Patmos’s rantings, the world around us has been shaped by those who do.

I woke this first morning with these thoughts. I was in a hotel room on the southern part of this sacred island, a small village called Grikos. Far above us, though obscured from my view, loomed the monastery of St. John the Theologian, built upon — and with some of the stones of — the ruins of a temple to Artemis.

Contrary to what’s generally believed, Patmos was hardly a deserted island when John was exiled there. In fact, there’s quite a lot falsely told parts of that story. The John exiled to that island wasn’t the same John the Apostle “whom Jesus loved.” Nor was the Apocalypse written from a cave on Patmos, but much more likely elsewhere, possibly Ephesus, the most famous centre of worship for Artemis.

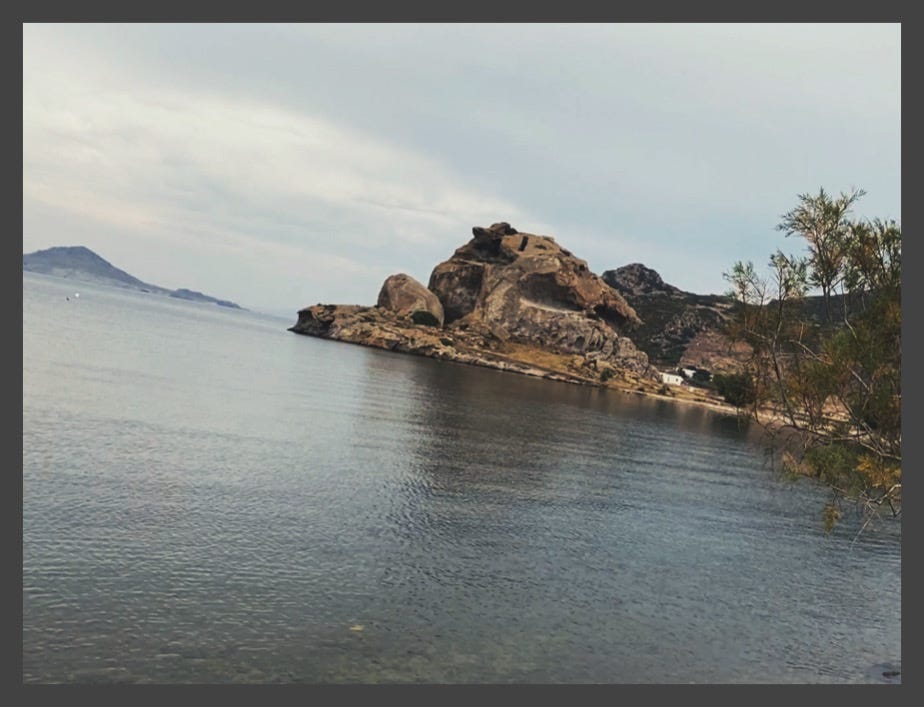

Regarding Artemis, whom the Romans called Diana, one of the oldest references to the island of Patmos describes it as “most sacred to Artemis.” It was said to have been raised from the ocean by Selene, the goddess of the moon, at the request of Artemis. Her temple was not the only one for the gods there: south, across the bay from my hotel room, constantly within view from each restaurant at which we ate, stands a strange rock named Kalikatsou, thought to have been the site of a shrine to Aphrodite. And in the harbor of the village Skala, which was a citadel for centuries before John arrived, there was a temple to Apollo.

So, I woke in the morning in a hotel room on an island once full of pagan worship, now known throughout the world only for an early Christian fanatic’s desire to see everyone he didn’t like burn forever in eternal fire. My first night’s dreams were full of strange images unearthing that buried history, and also — in a dream likely not meant for me — several contemporary Greek people arguing (in Greek) about which television show they would watch.

I was already late in waking. I’d not slept nearly as much as I’d hoped I would have, and the dreams were strange and far from restful, and only a few minutes remained before the hotel’s breakfast was no longer to be served. I remembered to put clothes on, wanting to at least make a good first day’s impression, and groggily negotiated coffee and boiled eggs. Most everyone else was finishing or had finished, and also didn’t know yet that I’m utterly incoherent in the first hour of waking, but I managed at least a few mumbled hellos, finally remembering why I was there.

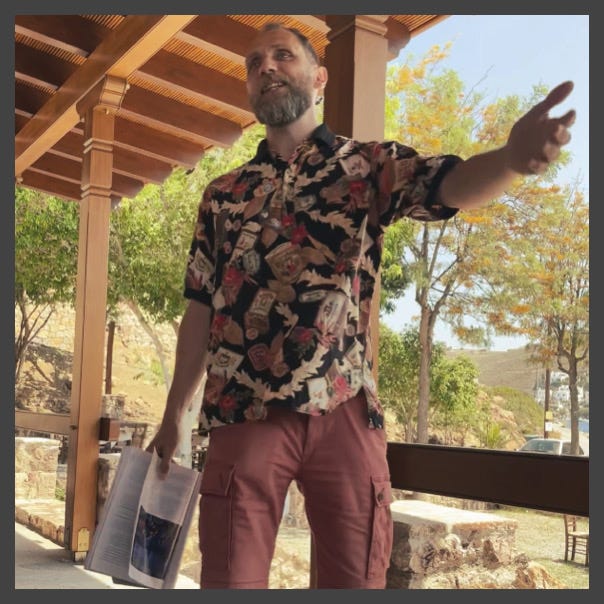

The first Black Elephant event was to start at 10, I think, and it wasn’t until at least 10:45 that I finally arrived, quite unfashionably late. Despite that, a hug and a loud greeting waited me there from Felix Marquardt, the man whose own brilliant madness had brought us to this island for the week.

What can I say about Felix that hasn’t already been said? You can easily read about him and his story with just a few keystrokes, or watch television or video interviews and listen to podcasts he’s been on. Also, I’ve already written a bit about him and about Black Elephant. What I can add, at least for now, is that if you’re going to walk up late to an event already starting, having Felix loudly greeting you in front of more than thirty other people makes it impossible to feel awkward or ashamed. Or, if you know tarot, he’s equally the Queen of Wands and the Knight of Cups.

Originally, the schedule was quite full, but after some initial introductions and discussion about the week, we were told to take most of the day just to meet each other, explore, get our bearings, or go swimming. After talking to a few people, I decided to go back, shower, and walk the hour or so journey from Grikos back to Skala. I’d like to say my primary goal was to get the lay of the land, to get a sense of the spirits of the place, or even to meditate or initiate a deep relationship with the island.

Actually I needed coffee to make in my room, and Skala has the only two grocery stores on the island.

It’s quite a walk, and rather beautiful. The road from Grikos to Skala follows the coastline after a curving ascent up a low ridge, and the views were breathtaking. In the afternoon heat, gentle breezes felt more like warm breaths sweetened with the scent of myrtle and occasional jasmine. Fennel grows everywhere there as if a weed, and I chewed on its thin fronds constantly on my walk. In fact, there’s quite a lot of food growing along the side of the road, sharply fragrant herbs, cultivated lemons, and a few berries and apricots within reach.

What I noticed particularly on the walk were all the elderly Greeks, including some quite wizened old women, driving scooters without helmets or care along the narrow and not entirely adequate road. Also, the road from Grikos to Skala is littered with hotels, guest homes, and other holiday accommodations catering to large waves of vacationers and a much smaller swell of religious pilgrims. You could almost not know the island has any religious significance walking through Skala, filled as it is with clothing boutiques, bars, and galleries. It’s got almost a hipster feeling to it, which meant at least that the coffee was unusually good.

Only lifting your eyes above the commerce, up to the menacingly militaristic-looking monastery on Mt. Patmos, reminds you there’s something older here.

I headed first to the larger of the two grocery stores, which are really both more like épiceries than groceries. In that one, I bought milk, coffee, sugar, and kefir, and spoke with the woman I learned was its owner. She offered me a piece of bread from a loaf wrapped in thin paper stamped all over with Orthodox symbols, and then told me only after I accepted: “normally, giving you bread signifies an invitation to come to church…”

Then, noticing the eyebrow I thought I’d only imperceptibly raised, she added, “… to some of us, anyway.”

I thanked her, downed the kefir and ate the slightly sweet bread. It was quite good, but not so good that it could convert anyone. I then bought another bottle of kefir and a mineral water, and walked back to Grikos. A little less then halfway there, I climbed down to a remote beach, swam for a little while, and made my way back to the hotel with another two hours to spare before dinner.

Sitting on my balcony, now on my second cup of coffee and third cigarette, I heard — and then saw —

peak over his own. “Do you have a light?” He asked, gesturing with a thin cigar in his hand.“Of course. Come over.” And, having heard him mention to someone earlier in the day that the coffee at the hotel was depressingly weak, I added “and I’ve got strong coffee.”

Martin’s lovely, really. I’d confessed to a mutual friend that I’d felt bad that I’ve never really been able to take to his writing. This happens, though, and anyway it’s not Martin’s writing where his profound power resides. He’s a story-teller, and good gods does he tell a good story with his voice (and, really, the rest of him), which I finally got to experience the next day. Having only read his writing, however, I wasn’t sure how well we’d get on, but yeah. He’s lovely: if the King of Cups mistook himself for the Knight of Wands, he’d be Martin Shaw.

Eventually it was time for dinner, where we were to be joined by someone quite unexpected. As a complete “co-incidence,” or at least absolutely unplanned and unforeseen, Gabor Maté and his wife Rae had both just arrived on the island. They were there to escape attention for a bit after several large events; but, after Felix found out they were on Patmos and asked them to join us, they agreed.

I think I was the only one who’d audibly reacted when I’d heard he’d join us, saying only “wow” really loudly. Gabor Maté, if he’s new to you, is how most people in the West first came back to an understanding of the relationship between addiction, trauma, disconnection, and the problems of disembodiment in modern capitalist society. Among the many influential ideas he’s introduced is that trauma (especially early trauma) affects the way we make decisions later in life, and unhealed trauma often leads to addiction. Also, the ideas of Dr. Bessel van der Kolk (The Body Keeps the Score) were influenced by Maté’s observations about the relationship between social or psychological problems and the body.

So has my own work. In fact, I reference Gabor Maté’s story about his own childhood in Hungary in my book, Being Pagan:

The writer and physician Gabor Maté, who is renowned for his work treating addiction, tells a story from his own childhood that shows this. When he was very young, too young to understand what was happening in the world, he constantly cried. This concerned his mother, who called a doctor to ask for help. The doctor replied that he would come check on the child when he could, but he was very busy because the children of all his other Jewish patients were also crying as well.

At that point, the Nazis were taking over Hungary, where he and his parents lived. Of course, Gabor could not have known this because he was still an infant. But what he and the other infants the doctor spoke of did understand was that their parents were nervous, scared, stressed, and worried. These emo‐ tions manifested through the bodies of the parents, which the children could then physically feel. And so they responded to their parents’ fear and anxiety by being anxious as well.

This ability to feel the emotions of others comes through the body. The body is constantly sensing, experiencing the physical world of which it is part. This is often called an “animal” sense, and we are taught to ignore such sensations and instead prioritise our thoughts.

Needless to say, then, I was was quite thrilled I’d get to meet Gabor. He and his wife Rae joined us for dinner, during which each table did a “parade,” answering questions about vulnerability and listening to each other as they do answer, too. Rae was at my table, and she’s a deeply fascinating and kind person in her own right. That they’re both together the parents of Aaron Maté makes a huge amount of sense: only a person with that much emotional support from parents could possibly be brave enough to write what he does.

8 June

I had really strange dreams again, and slept fitfully. This would recur again and again throughout the week, leading me to be quite damn tired by the end of my time on Patmos. Also, I’d gotten a sunburn from the day-before’s walk, leaving an amusing reverse print of my tank top in pale skin against the deep red of the burn on my arms and around my neck.

All that said, I was in quite a better mood, and deeply optimistic. I took breakfast without as much rush, managed to be a little coherent when speaking to a few others, and arrived at our next meeting a little early.

There were a bit more than thirty — I think perhaps thirty-four of us — on the island for the event. A few had traveled from the United States, many from France and the United Kingdom, as well as one trio from Iceland, another trio from Sweden. Most significantly, quite a few had come from Africa and the Middle East: a feature of Black Elephant, too rare in other organizations, is a kind of native diversity born of the very project itself. That is, it’s part of the structure itself, rather than something a DEI consultant was paid to create.

I really, really, really love these people. Any other way of putting this would be insufficient. Even the ones I’d never met before felt like close kin, especially as the week went on. Each day, a handful of people were chosen to speak publicly, answering three questions: who are you, what hurts, and what keeps you going? Sure, you could try to fake-answer these, give some pleasant-sounding response that doesn’t really reveal your core, but in such a situation you find quickly that there’s something deep inside of you that wants to be expressed, that wants to answer.

I was part of the first group. I hadn’t thought on the questions beforehand, and so I just talked, telling a story I remember from my childhood. My younger sisters and I lived in a dilapidated and constantly leaking A-frame house in the middle of a clay pit, the best our Appalachian childhood had to offer us. Also offered to us was an open sewer, the results of a broken septic tank flooding part of the pit. The stench was awful, particularly during the hot Ohio summers. But there’s a funny thing that happens to plants growing in a patch of soil watered with human shit and piss: they grow, and they grow large. Particularly in the summer, the wildflowers rooting in that miasmic dirt were startling to behold, more vivid and brilliant than any blossoms I’ve seen in my life.

“Open sewers grow gorgeous flowers,” I said, in answer to “what keeps me going.”

That same morning, we got to hear Martin Shaw’s first story. I’ll not try to retell it here, and it’s anyway better to hear stories like the one he told actually told, not written. I’ll say only that you really must, if ever given the chance, go hear him sometime. The experience is quite incredible.

That afternoon, I wrote most of what became the second installment in this journal, and then hurried to the first of several HOME sessions hosted by

and Anna Björkman. During a part of it, we were asked to speak a word or phrase we’d encountered thus far that was still often in our consciousness, and I was quite humbled that several people repeated “open sewers grow gorgeous flowers.”The work Dougald and Anna do runs quite parallel to the work of Black Elephant (and, in fact, it was early meetings including Dougald which birthed the idea). If you’ve not met Dougald in person, I do hope you one day do. Keeping with the tarot theme, he’s got the mind of the King of Swords with all the calmness of the Queen of Pentacles, an almost impossible balance that nevertheless manifests in his physical presence even more so in his writing. We’re roughly the same age, but he’s what I want to “grow up to be.”

After the meeting, there was a short break and then dinner again. I guess I should at least mention the food, as it was all quite good. We all ate a lot of Greek salads and tzatziki, which is I think probably what one does best on a Greek island. Others also ate calamari, which I cannot eat, and then sometimes chicken souvlaki, sometimes fava, sometimes chick peas, sometimes a fragrant and sweet aubergine dish called Imam Bayildi. Despite being quite famished by the time dinner came around, though, it was always the conversations at the table I hungered for, and I think others felt the same.

That night, I talked with several others about god. By then, the word had been come up repeatedly, and we were, after all, on an island known for god(s). It’s a funny thing to be the only avowed polytheist in a place like that, among so many discussions of god but none of gods. Of course, the closer you listen to such invocations of “god,” the more you begin to notice that they don’t all seem to be talking about the same god at all. Not just between the Muslims and the Christians, but also among each group, diverging narratives and descriptions become almost impossible to ignore from the outside.

On the other hand, no one speaking of a singular god seemed at all bothered by these incongruities; on the contrary, it seemed to add something quite beautiful. There are some times I look back just a few days from today and find myself remembering these dinners not occurring on Patmos but instead the great walled gardens of Al-Hambra, fragrant jasmine and smouldering incense wafting over cakes made of sweet figs. That is, it felt Andalusian, and older and more authentic cosmopolitan conversation, punctuated with poetry, performance, and song.

Well—until I got angry, for the first time in perhaps a decade, maybe two. Even that felt quite okay, and it’s a tale for the next journal.

You wrote in such a compelling way, I felt I was there too....And the cliffhanger now about anger!! Am all ears, ah well eyes, waiting for more.....

These are lovely journals and it sounds like a lovely trip. How wonderful to have met Gabor Mate! I was blown away by his most recent book, especially reading it as my daughter was still in her early infancy. Thank you for sharing.