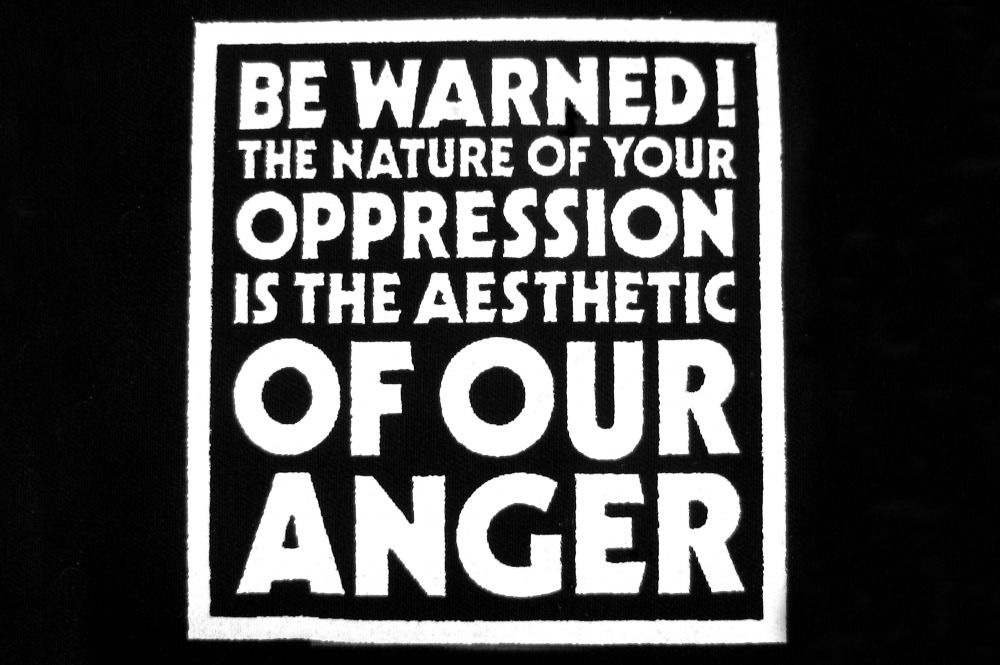

"The Aesthetic of Our Anger"

Anti-Racism, Anti-Capitalism, and the Aesthetics of Fascism

A major premise of my work lately—and especially my still-in-process manuscript—is that identity politics, social justice, and “intersectionality” (generally called Woke Ideology) are all essentially counter-revolutionary reactions to capitalist social disruption.

To those new to this way of thinking—or to the countless Marxist critiques of Woke Ideology—that sentence above might sound a bit absurd. After all, movements like Black Lives Matters, Antifa, and the more distributed and less centralized embrace of newly-created conceptions of gender (declarative gender, basically being really the gender you feel yourself to be) all have an apparent anti-capitalist aesthetic to them. And, actually, there are absolutely people within these tendencies who critique or identify themselves as anti-capitalist. However, the ideological or political movements themselves are not essentially anti-capitalist, and are themselves amenable to capitalist society.

To understand this, we first need to clarify that there’s a subtle but very important difference between a general social position and a specific ideological framework. For example, there is anti-racism and there is Anti-Racism. The first is a position: ‘I am against racism.’ The second is a formal ideological movement created by specific thinkers and writers (Ibrahim X. Kendi, Kimberly Crenshaw, etc) which defines what it means to be “truly” against racism.

We can see this same kind of distinction in the difference between anti-fascism and Antifa. The first means to be against fascism, the second is perhaps best described as brand-name anti-fascism, or maybe anti-fascism™.

The difficulty that arises in these distinctions is that it’s rarely clear what is being discussed. Worse, the two levels of meaning often operate in conversations at the same time, and not everyone involved is clear what is really being meant. Also, it leads to a kind of slippage or drift in meaning such that entirely new ways of seeing political problems are created without anyone really noticing what happened.

The best example of this that I can offer you is the term “white supremacy,” which once referred to a specific (and horrible) ideological stance. White Supremacists are people who believed that whites were superior to all other people and should have all positions of authority in politics, business, and society. A similar term for them is White Nationalist—specifically, people who believed that white people should have their own nations and homelands and be able to eject all people who were not white.

There is another meaning of white supremacy now (notice that I did not capitalise it here). In this sense, white supremacy refers to the current social, political, and economic situation of the United States, Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United Kingdom (as well in some reckonings all of Europe). Also, for some Anti-Racist theorists (note the capitalisation there), white supremacy itself is seen as a kind of structure or system a bit like the way Catholics understood Original Sin: every white person has to reckon with, dismantle, or even atone for their inherent (or inherited) inner white supremacist beliefs.

At the root of this confusion is something very, very human and particularly endemic to the English language. If you remember your high school English classes, think of the difference between a noun and a proper noun. We capitalise some nouns and do not capitalise others, but the distinction is only obvious in writing, not in speech. Also, we don’t use definite articles for most nouns, as opposed to languages like French or German. That makes it easy for nouns to slip into adjectives, which is core feature of English without which we couldn’t really communicate.

A brief example of how crazy English can be are the following two words: “shop” and “bicycle.” Each of those words are nouns (a shop, a bicycle) and verbs (I bicycled to the shop, I shop for bicycles). They each also can act as adjectives, so that you can speak of a bicycle shop (a shop where you buy bicycles) and also a shop bicycle (a bicycle that belongs to the shop). Other languages often don’t have this problem. German fixes this problem by just smashing the words together into a new word (Fahrradgeschäft: bicycle shop). French fixes this confusion by adding an article between the words, usually ‘de’ (of): magasin de vélo (shop of bicycles).

Words dance around and change positions in our speech all the time, and we do this effortlessly. The problem is that is is so unconscious we are not always aware of the way this switching changes the meaning of terms, nor of what those new configurations mean. We don’t always know if someone is talking about an ideological formation or just a behavior or position, and this leads to endless confusion for many people.

With all that in mind, consider again the difference between anti-racism (being against racism) and Anti-Racism (a specific and American-centric ideological framework developed by a handful of academics, theorists, and activists). The first is term I think every single one of my readers would identify with, as do I. The second is a specific ideological framework which I think very few would identify with because of its specific positions.

The specific positions of Anti-Racism that most of you (and I) would likely reject or critique are as follows:

All white people are inherently racist and continue to be even when they try to be anti-racist

All white people are privileged (even white people in extreme poverty or homeless white people).

Racism is at the foundation of all economic exploitation.

“Anti-Racist discrimination”1 is the only way to end racist discrimination.

The core problem with Anti-Racism as an ideology is that it skirts the issue of capitalist exploitation altogether. In its proposed alternative to the current racist society, we’d have fewer rich white people and many more rich black people. That is, we’d still have rich people, and we would still have capitalism. But it would be a more diverse and racially-equal capitalism, which to their view is an ideal society.

It’s here that you can maybe understand why anti-capitalists—specifically Marxists—reject this framework. For them, the ultimate goal is an end to capitalist exploitation of humans and nature. They also see racism as a kind of handmaiden to capitalism, or what I call a “governing aesthetic.” Race is used as a way of separating the exploited working classes into further categories of exploitation. Black or Hispanic people in the United States, for example, are more likely to only be offered manual labor jobs (agriculture, domestic labor, construction, restaurant work) which pay poorly and have high rates of injury. White people are also shunted into those jobs at very high rates, but it’s also possible with a college education and the right social training for a white person to get less physically arduous jobs and higher wages. It’s much more difficult for people who are not white to get those jobs.

The core problem, however, is that those manual labor jobs are so poorly paid and dangerous because of capitalism. Even if there were a true demographic representation in each field (black people comprise 13% of the US population, so that would mean 13% of all jobs everywhere—including CEO and governing positions—held by black people), those lower end jobs would still be as dangerous and poorly-paid. That is, the material conditions of the poor wouldn’t change, nor would the numbers of poor change, only the aesthetics of poverty.

I use the term “aesthetics” for an important reason here, because it’s a key concept for understanding fascism from a Marxist perspective. To understand why, consider this quote from the Jewish Marxist writer, Walter Benjamin, who fled Nazi Germany for France, then Spain, but died there (likely by suicide) when Spain ordered him deported back to Nazi-occupied France.

The increasing proletarianization of modern man and the increasing formation of masses are two sides of the same process. Fascism attempts to organize the newly proletarianized masses while leaving intact the property relations which they strive to abolish. It sees its salvation in granting expression to the masses, but on no account giving them rights. The masses have a right to changed property relations; fascism seeks to give them expression in keeping these relations unchanged. The logical outcome of fascism is an aestheticizing of political life.

This quote is from what I consider his most important writing, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. In it, he examines the way our relationship to art and to our sense of identity changed on account of the industrialization (mass production) of art. By “art” he doesn’t merely mean the sort of stuff you see in museums, but rather all cultural expression itself, including societal rituals.

Industrial (capitalist) production of art altered the way we saw ourselves as groups. Before capitalism, we identified with the specific people around us, where we lived, who are parents and family were, and who we felt ourselves to be in relationship to history and the land around us. Capitalism introduced to us the idea of mass identity, that each of us were part of much larger groups of people whom we might never meet and with whom we had no shared geographical, historic, or really any other commonality except for created identities.

How this happened is beyond the scope of this essay (I really recommend reading Walter Benjamin’s work as a beginning to this2), but what’s important to understand is that this is how we came to believe race was an actually-existing thing that defines groups of people. “White” is a very new concept and a very new category, one that arose along with capitalism itself. So is “black,” as well as all other racial categories.

If this is difficult to grasp immediately, consider the term “millennial,” which was created by two pop sociologists (neither of which worked at university nor had previously studied social trends) in the United States. Those authors wrote several books proposing a theory that people born during similar times all have similar values and social effects. Before its creation, no one thought of themselves as a millennial, nor did anyone believe that a generation was a real thing. Now, especially because marketing firms picked up the idea and used it to shape consumer preferences, people treat millennial and other generational categories as they are an obvious and true classification, despite being completely made up out of nothing.