Perhaps the most terrible secret I have ever learned is that we are alone fully responsible for our own joy.

I know this probably sounds like “white light” bullshit, especially if you consider yourself a radical or a leftist. Even more so if you’ve been on the internet for too long and seen the memes like this:

The “White Light” movement, or “white light spirituality,” stems from a philosophy in the 1800’s called New Thought. You already know New Thought if you’ve ever encountered the phrases “mind over matter,” or “law of attraction,” or just the idea that thinking positive thoughts makes things in your life better.

Much of New Age spirituality—all the ideas about raising your consciousness or “vibration” to make your own life and the lives of others around you better—descends from this school of thought, as well as much of the faith healing (including Mary Baker Eddy’s Christian Science) that ran rampant throughout the United States in the 1800’s and 1900’s.

All these philosophies teach basically the same thing: that most of the shitty circumstances in life can be changed with application of mental discipline or a change of thought patterns. This includes physical conditions such as illness and poverty, as well as social problems such as relationship issues, loneliness, depression, and alienation.

And most of it is bullshit, but unfortunately most of it is also true.

There is a school of psychotherapy, the one I’ve seen have the most profound effects for many of my friends who’ve used it, called Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. Unlike more traditional approaches (often involving pharmaceuticals), CBT1 attempts to find the core beliefs a person tells themselves which lead to destructive or unhealthy patterns in their lives, and then guide the person into a place where they can change those beliefs.

For instance, consider a person who is constantly depressed and has a long series of failed relationships. The therapist using CBT would attempt to discover what that person thinks about themselves and how they narrate those relationships. From there, the therapist would then try to tease out the core beliefs that might be leading the person to sabotage themselves and those relationships. Once those are identified, the therapist then would suggest new beliefs and thought patterns that might help the person become less depressed and have more success in relationships.

The key question constantly posed to a patient in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy is some form of, “have you tried thinking a different way about this?”

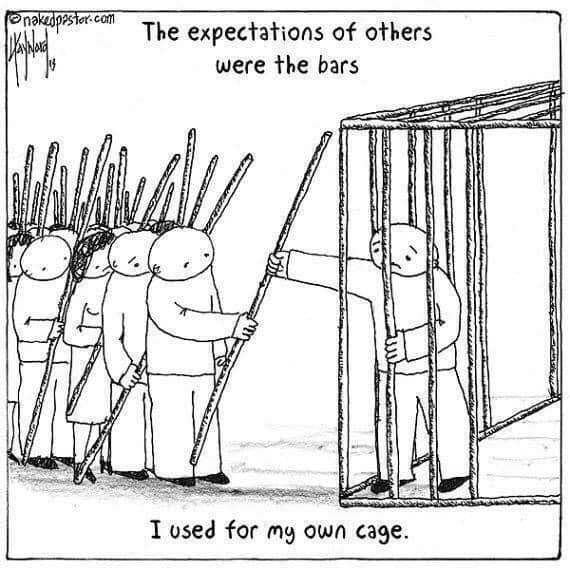

A person who, for example, believes that they will never have healthy relationships because of past abuse would be encouraged to question this belief, possibly by questioning the relationship between those events and how they define themselves. Perhaps the person believes in some way they ‘deserved’ the abuse, or that they can never heal from that pain, or that they are still being abused even when they are not. Those beliefs prevent them from having healthier relationships, and thus need to be replaced with more useful beliefs.

By this point, I’ve likely triggered an emotional reaction in some of you reading this, because my description of this scenario seems to “victim blame,” to put the onus and responsibility for all those situations on the suffering person, rather than the person who caused the suffering in the first place.

Please feel free to sit with that emotion, because that’s exactly the kind of reaction I used to have to such narratives, too. Especially if you’re a leftist, the very idea that the suffering of a person might be linked to their thought patterns rather than external circumstances seems like the core belief of capitalism: “if you’re poor, it’s your own fault.”

Stepping back a moment, however, it’s not hard to see that “if you’re poor, it’s your own fault” is also a core belief that a therapist using Cognitive Behavioral Therapy might try to tease out and help the person change. The key here is the word ‘fault,’ which belongs to mental framework in which wealth and poverty are signifiers of a moral order.

Put another way, “if you’re poor it’s your fault” is a belief that wealth is tied to morality. The more moral you are, the more wealth you will have; the less moral you are, the poorer you will be.

The inverse, which is what Nietzsche called “slave morality,” is also a false belief: the wealthy are immoral, the poor are righteous. This, of course, forms the basis of a lot of current leftist thought, especially in the United States, and is ultimately as self-defeating of a belief system as the one it attempts to fight.

Poverty and wealth are material conditions, not moral positions. There is no Judeo-Christian mono-god distributing wealth to his elect, nor is there a social justice version of that god recording the suffering of the poor into moral ledgers from which they can later draw social capital.

And while Marx showed that the conditions of the poor are orchestrated by those who already have accumulated financial wealth,2 the whole point of The Communist Manifesto and the rest of his works was that the working classes could significantly better their conditions by reaching a mental state called “class consciousness.” There is no moral fault nor blame to be ascribed to the capitalists, nor to the working classes, only a social arrangement that can be changed if the workers want it badly enough.

That is to say, “New Thought” and white light spirituality have something in common with the core materialist assertion of Marxism. Constrast this with Critical Race Theory and the narcissism of social justice identity politics. These latter frameworks are moral frameworks, assigning blame and fault to an apex-oppressor class (white cis-het-abled men) who posses an ineffable yet omnipotent morally-evil force called “privilege.” The rest of the world, the “good” people, are relentless and eternal victims, unable to ever attain happyness, joy, or even a stable existence because of esoteric and occulted forces like “white supremacy” and “cis-hetero-patriarchy.”

I once thought these things too. But I also thought other things, like “I’ll always be poor because of capitalism” and “I will never be treated as an equal in a relationship.” It turns out these were all mere tendrils of more inextricable core beliefs, especially “I have no power over my own life,” “I don’t deserve better,” and “my suffering makes me morally righteous.”

These manifested in ways I now find fascinating but, for awhile—when I first learned to explore them—embarrassed the hell out of me. For instance, whenever I would meet new people who seemed to be healthier, happier, and to have more wealth than I did, I assumed they had either done something immoral to get to that place or were themselves amoral. Because how could they possibly enjoy life when there is so much suffering in the world? How could they afford to eat healthy, go to the doctor, get their teeth fixed when they needed to, have time to enjoy life, buy new clothes, and all that without deadening their souls?

Their “secret” was embarrassingly simple and terrible: they merely let themselves.

An opportunity arrived in front of them and they pursued it, rather than telling themselves it “wasn’t for them.” They saw how they wanted to live and then lived that way, without endlessly debating whether or not they “deserved” such a life. They pursued relationships that reflected the kind of love they wanted to both give and receive, rather than settling for the first unstable, broken person who showed unhinged interest in them. And they left relationships that didn’t bring joy or reciprocate the effort, attention, and care they offered.

For such people, it’s not really a secret at all. It’s quite obvious to them, at least once they figured it out. Now that I understand this too it’s the most gods-damned self-evident thing. The secret is not postponing your life, and no longer holding yourself hostage to ideologies or moral frameworks that assign value and fault to suffering or joy.

The most terrible part of this all for me is the “secret” of wealth. My income has barely changed over the last six years, yet there’s so much wealth in my life that I feel absurdly rich. Wealth isn’t money, and poverty is not the lack of money. Wealth comes from the earth, our relationship to it and to our bodies, not from dollar signs and paychecks. It’s the friends and relationships in your life, the air you breathe, the life around and through you. It’s not something anyone “deserves,” but something anyone can recognise3 in their own life.

The financially rich are often just as miserable as the poor. I now personally know more millionaires than I ever thought possible, and most of them don’t get to enjoy any of it. That’s the other terrible part of this “secret:” the feeling of lack and want never go away no matter how much you have, unless you learn to enjoy what is already around and in you. Not just enjoy, but to let yourself feel joy, that terrible secret both the poor and the rich can learn if they let themselves.

Joy as Anti-Politics

Others have tried to write a framework for a “politics of joy,” with absolutely depressing results.4 All such efforts will invariably fail, because joy is one of the few human experiences that has successfully resisted politicization.

Joy is neither left wing nor right wing, and no politics can ever create joy. The entire goal of modern politics and activism—just like the goal of consumer advertising—is to inculcate, harness, and re-channel mass disaffection, despair, and the feeling of lack and insufficiency towards the goals of a few.

To do so, they must convince us that we are not responsible for our own joy, that something or someone outside ourselves is standing in the way of our fulfillment.5 This is the same whether that external is an identity group (Muslims, men, the rich) or an intangible system (white supremacy, immigration, patriarchy, capitalism, communism), just as nations and monotheism conjured external enemies and future rewards to compel the masses towards violence.

Politics is ultimately anti-joy. People in joy lack nothing and therefore want nothing. Their desires are complete, at least while they are in joy, because joy itself is its own desire. You can be starving, or in prison, or on your death bed and still feel joy. It is a particular orientation towards experiences, not a result of experience.

As such, it’s ultimately the opposite (and only cure) for ressentiment. Ressentiment says, “I cannot feel joy and therefore no one should.” It actively prevents and walls out experiences of joy, and to do so it must also choke out the joy of others.

Consider the bitter and barren old woman who sneers at the laughter of playing children, demanding curfews and laws to quiet them. She is in ressentiment. She is someone who has refused joy—not because she had no children, but because she made having children a condition of her joy. The bitter man who shoots his former co-workers when he is laid off is likewise in ressentiment, because he made having a job the condition of his joy. The woke non-binary asexual who demands all displays of gay male ‘kink’ sexuality be purged from Pride festivals, and the person who demands mass language changes (“chest feeding” rather than “breast feeding,” or the elimination of all potential triggers from the public speech of strangers) are likewise in a state of ressentiment. 6

Ressentiment is reductive. It must reduce the experience of others to the joyless state of the person in ressentiment. Joy, on the other hand, is expansive. It is contagious, like the laughter of a child. It wants to share, to bring others into the experience. When we see the moon rise full and rose-gold over a hill, or see a rainbow, our first instinct is to call all those around us in hearing distance to share our wonder.

Join me, joy says, leaping from our hearts.

Suffer as I suffer, ressentiment scowls, withering our souls.

Joy has no external source, and it is not based on circumstances. Joy does, however, lead you to change circumstances, to pursue situations in which joy flows easier, to stop striving for or against things to achieve results that will not give you joy.

There is no joy in striving against capitalism, but there is also no joy in striving for capitalist ends, either.7 Instead, there is joy in the raw life that capitalism, politics, and the state obscure—the human moments, the moments of humans in—and as—nature.

I took a brief pause while writing this to ride my bike to a store. My path led me through a forest divided by a road, and while riding home, the sun warming my skin erotically, the scent of the forest filling my nostrils and mind, I forgot myself completely, forgot this essay, forgot all of it and just was. A fawn crossed my path, regarding me calmly, unstartled. I laughed and said hello, then continued my ride home.

That is the joy of raw life, a joy which led me to live where I am, to give more time to the nature around me and to give more time to myself to be in that nature so to be in more joy. In such moments, I need nothing, I lack nothing, and just am. So I fill my life with more moments such as that, cultivating them like one cultivates a garden.

There is nothing political in those moments. The most that modern politics can do is prevent those moments: paving over forests, putting up fences, making it illegal to be in those forests. Even if a politics of joy were possible, it still couldn’t make those experiences happen.

The only thing which leads us to that joy is our other experiences of joy. With each moment of joy, we learn to look towards more joy, to face more often the horizon as the sun sets or the moon rises. We learn to cultivate friendships where joy is a mutual goal (and yes, to let die friendships where joy suffocates in the void of ressentiment).

We learn to change our very way of seeing the world, to exorcise from our hearts all the beliefs which choke out our joy. We stop preventing, sabotaging, and prohibiting ourselves, just as we stop preventing, sabotaging, and prohibiting the pursuit of joy for others.

We learn to let ourselves be in joy. We learn to manifest joy. And the terrible secret becomes the most beautiful secret: we are the only ones who can do so.

Brief Notes

For an in-depth discussion of ressentiment, see my essay “The Vampiric Gaze.”

On Saturday night I had a fascinating conversation as a guest of Gordon White. We discuss politics-as-religion (they're the same thing), identity politics' divorce from external reality, the problems with CRT (especially its pro-capitalist foundation), the complete mess that US anarchism is, plus lots of Ursula K Le Guin and the magical potential of the pre-left. It was really, really fun. Go watch it here.

My new course, Being Pagan, is now scheduled for a second iteration because the first one filled up so quickly. That starts in October, and you can enroll here.

Disambiguation: CBT also means something a little different to some of us more adventurous gay dudes. Also note that both forms of CBT have much more revolutionary potential than CRT.

Hold this point in your head for a bit. I’ll mention something crazy about it later in the essay.

"manifest”

Joyful Militancy, for example, which really will make you want to suicide.

There’s also really good money to be made in this sort of thing, by the way. Rachel Cargle (the woman who popularized the meme about manifesting vs. white supremacy) is currently worth at least 3 million. But maybe she manifested it?

The key here is the demand that others abstain. Ressentiment is not just an internal state, but rather one that seeks to prohibit the behaviour of others so that the external world validates and maintains the internal trace of trauma. This is what Kirkegaard called leveling, the demand that everyone conform to the conditions of the worst off, rather than the egalitarian impulse to better their conditions.

Remember footnote 2? Deleuze expounds upon the concept of ressentiment to show that the capitalists—through their need to prohibit others from having access to the means of production—are doing so out of ressentiment. Basically, the capitalist is not producing for themselves, and therefore prohibits others from producing for themselves (and therefore for the capitalist). The key phrase here is “I do not take care of myself; therefore, take care of me at the expense of yourself,” which is also the demand of an abusive partner.

Very cool.

I needed this one! Thank you <3