This is an excerpt of my manuscript-in-progress on Woke Ideology, which will be submitted soon and published at the end of this year. The thrust of the manuscript is that Woke Ideology functions as a religious system for its adherents and acts as a replacement for traditional leftist politics which instead supports capitalism, rather than opposing it.

This excerpt, as with all previous excerpts, is available in full to paid supporters of From The Forests of Arduinna, and a preview is available to all subscribers.

If you are not yet a paid supporter, or if you would like to upgrade your monthly subscription to an annual subscription, until the end of May 2022 you can do either of these at a reduced rate. Annual subscriptions are 20% off, and monthly subscriptions are 10%.

Use this button to subscribe or upgrade to an annual subscription:

Or this button to subscribe as a monthly supporter:

The Woke and the Working Class

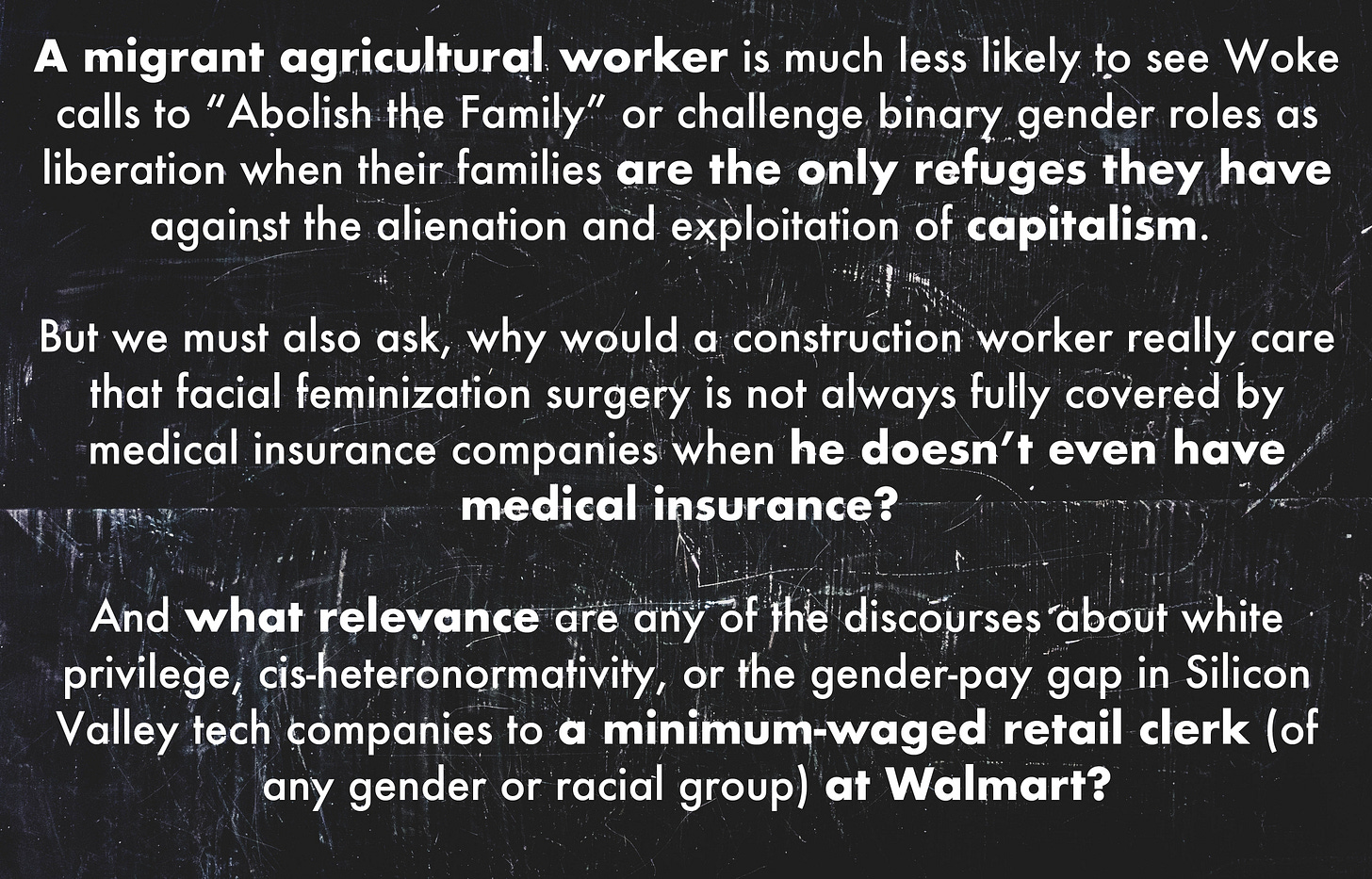

The identity hierarchies and categories created though Woke Ideology— of race, ability, gender, and sexual orientation—glaringly omit a specific division which any Marxist immediately can sense: that of class. In fact, class cannot be introduced within these categories without undermining the entire system of categorization.

Consider: what does a jobless and homeless “white heterosexual able-bodied cis-man” really have in common with a CEO who possesses all those same identity traits? Or for that matter, what do certain of a CEO’s employees have in common with him except for those identity markers?

This is the reason why any Marxist (especially black Marxists such as Adolph Reed) who attempts to re-introduce class as a framework and foundation for solidarity or radical organising is typically smeared as a “class reductionist.” Class destabilizes the entire discourse by looking for commonalities and differences along a fully different set of co-ordinates which cut across all the other identity categories. It divides every supposedly unitary oppression grouping by asking a simple question: do you have access to wealth and the creation of more of it? Or must you sell your time, your body, and your labor for even the minimal means of your survival?

Most intolerably of all, the question of class threatens the stability and position of those who argue most on behalf of Woke identity co-ordinates. Consider a short list of such theorists and activists: Rachel Cargle, famous for her statement “I refuse to listen to white women cry,” owns several businesses and has a net worth estimated at 3 million US dollars. Judith Butler, the founder of modern declarative gender theory, is reported to have about 9 million US dollars in wealth. Robin DiAngelo, who runs a consulting business for corporate diversity programs and who is the author of the book White Fragility, is also a multi-millionaire, as are Ta-Nehisi Coates, Ibram X. Kendi, and Kimberly Crenshaw.

The problem for such people is that, from a class framework, they have much more in common with the capitalists than they do with the proletariat. Their class identity would thus alienate them from the groups for whom they position themselves to speak, while also giving lie to the idea that any identity group is a coherent category.

Understanding the Professional-Managerial Class

The class positions of the primary theorists of Woke Ideology are actually the reason for the complete absence of class analysis within their criticisms of race and gender. Donna Haraway, whose work opened the way for Judith Butler and others to move feminism away from class analysis towards identitarianism, explained why she thought such a transition was necessary in A Cyborg Manifesto:

“For me—and for many who share a similar historical location in white, professional middle-class, female, radical, North American, mid-adult bodies—the sources of a crisis in political identity are legion.”

Haraway was writing after the Combahee River Collective Statement1, whose assertion that identity must be a primary organizing foundation for all political struggle significantly shook the left’s understanding of class and sex. However, there was also another profoundly influential essay published a few years before which her admission of location within “white, professional middle-class” was reaction.

That essay, written by Barbara and John Ehrenreich and published in 1977 in the journal Radical America, offered a completely different framework for understanding the failures of leftist organizing in the United States. For the Ehrenreichs, the core issue was not the difficulty of defining women or the need for better understanding of identities, but rather the ascendancy and dominance of the Professional-Managerial Class (PMC) to which not only the authors, but also Haraway, the members of the Combahee River Collective, Judith Butler, and all the current theorists of Woke Ideology belonged.

The Ehrenreichs defined this Professional-Managerial Class as follows (emphasis mine):

We define the Professional-Managerial Class as consisting of salaried mental workers who do not own the means of production and whose major function in the social division of labor may be described broadly as the reproduction of capitalist culture and capitalist class relations.

Their roles in the process of reproduction may be more or less explicit, as with workers who are directly concerned with social control or with the production of propagation of ideology (e.g.; teachers, social workers, psychologists, entertainers, writers of advertising copy and TV scripts, etc.). Or it may be hidden within the process of production, as is the case with the middle-level administrators whose functions…are essentially argued by the need to preserve capitalist relations of production. Thus we assert that these occupational groups—cultural workers, managers, engineers and scientists, etc.—share a common function in the broad social division of labor and a common relation to the economic foundations of society.2

The PMC roughly translates into the idea of “white collar workers,” those who work in offices rather than in service, factory, or manual labor jobs. The Ehrenreichs’ definition is broader, however, in that it includes people who work in ideological professions which do not have a specific administrative role, including artists, writers, entertainers, professors and other educators, psychologists, and social workers. As ideological workers, their function is not in physical production, but rather in the “reproduction of capitalist cultural and class relationships.”

Key to understanding the PMC is that they are a small subsection of the working class itself, meaning they do not possess their own means of production and must sell their labor. That is, they are not actually part of the capitalist class, but nevertheless share and reproduce the cultural values of the capitalists. Barbara and John Ehrenreich describe them as a “derivative class,” a class derived from the masses of the proletariat to support the capitalist order.

…The very definition of the PMC—as a class concerned with the reproduction of capitalist cultural and class relationships—precludes treating it as a separable sociological entity. It is in a sense a derivative class; its existence presupposes: (1) that the social surplus has developed to the point sufficient to sustain the PMC in addition to the bourgeoisie, for the PMC is essentially nonproductive; and (2) that the relationship between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat has developed to the point that a class specialising in the reproduction of capitalist class relationships becomes a necessity to the capitalist class. That is, the maintenance of order can no longer be left to episodic police violence.3

In other words, the PMC is a highly-paid subset of the proletariat whose salaries and very existence derive from their role as reproducers and guardians of the social order. This work exists so that the capitalists do not need to use relentless, naked violence to keep workers in line. They create the cultural forms—the “structures” of domination—which ensure the rest of the working class remains content with their economic situations. They train, civilize, supervise, treat, and amuse the producing classes—the factory and service workers, the manual and agricultural workers, the “blue collar” sorts—and by doing so smooth over and mollify class tensions so to ensure the perpetuation of the capitalist order.

The PMC is also what has been called by conservative critics the “liberal latté-drinking urban elite,” since their values, professions, and lifestyles—even among those who hold to leftist political frameworks—are heavily aligned with an urban (bourgeois) cultural sensibility. Demographic polling on political issues supports this critique—those with higher degrees and higher incomes who live in urban and suburban areas show higher support for liberal or progressive policies and candidates than those with lower incomes, less education, or those of their cohort living in rural areas.

In this way, the PMC also maps closely to the older Marxist analysis of the “petite bourgeoisie” (the ‘little urban class’). These were the small shop owners, doctors, lawyers, and people in other highly-specialized and rare professions who did not work for a wage but were nevertheless not true capitalists (because they did not exploit the labor of others to increase their capital). Despite not actually being engaged in capitalist exploitation, their cultural and political values aligned with the capitalist class, and they strongly supported political repression of the lower classes.

The Professional-Managerial Class, then, is an evolution or expansion of the petite-bourgeoisie with the important distinction that they are often also salaried.

The PMC versus the rest of the working class

The observation that the PMC is not actually engaged in physical production is deeply important for understanding the tensions and diverging concerns between them and the rest of the working class. We can easily sense a vast difference in values and economic concerns between a woman working in a meat-packing plant in the Des Moines, Iowa and a woman running a yoga studio in Portland, Oregon. We can sense this same difference when we consider other comparisons:

A black trans woman working for an investment bank versus a black trans woman working at McDonald’s

An Hispanic woman cleaning houses through a maid service versus one teaching gender studies at UCLA.

A black male sanitation worker versus a black male editorialist for The Atlantic

A white male construction worker versus a white male database administrator.

Besides deep differences in compensation and standards of living, not to mention the vast disparity in the physical effects on the body, the relationship between the PMC and the rest of the working class is an unequal relationship of consumption. That is, the rest of the working class is producing the physical goods and services (housecleaning, food and food service, construction, sanitation, dry cleaning) which the PMC rely upon for their elevated standards of living.