This is an installment of a new short-essay series on the concept of political theology and how it’s crucial to understanding modern political problems.

Read the introduction to this series here.

Most of us probably understand the Anthropocene as the current epoch we are in, a shift in “geological time” during which human actions are radically changing the shape of the earth. This, anyway, has been the most common definition, but no one’s really been able to agree on when it started or even if it’s really a thing at all.

The Anthropocene first came into public consciousness in the year 2000, when two scientists wrote a letter in the journal of a now-defunct international research program (the International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme) suggesting the term. After offering a depressing litany of the ways anthropogenic (human-caused) activities had changed the earth, they then wrote:

Considering these and many other major and still growing impacts of human activities on earth and atmosphere, and at all, including global, scales, it seems to us more than appropriate to emphasize the central role of mankind in geology and ecology by proposing to use the term “Anthropocene” for the current geological epoch.

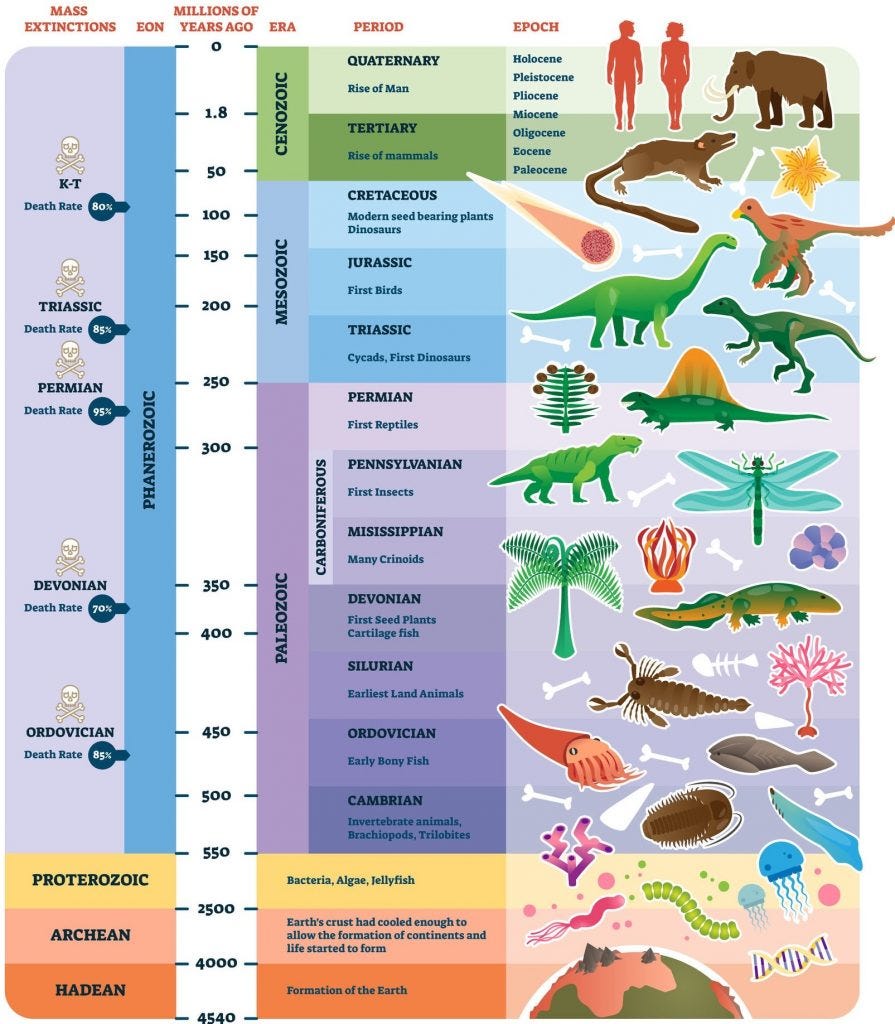

Geological epochs are just one kind of division in the much larger classification system of earth time. They are also a bit difficult to picture in ones head, so here’s a graphic made for children which is much, much better than any of the “adult” explanations:

On the graphic, you can see that an epoch is much shorter than aeons (like the Hadean), eras (such as the Paleozoic), and periods (Jurassic, etc). There are even smaller divisions of time (sub-epochs, ages), but those don’t appear on this graphic and they are even harder to define than the larger divisions.

Now, before we get bogged down in the scientific details of all this, it’s worth remembering that this entire classification system is quite new. In fact, it wasn’t until the 1800’s that the Christian belief that all the world was covered in a singular flood started to be challenged in the West.1 Previous to this point, though people already understood how layers of rock are formed from sediment, the discovery of unexpected fossils in certain layers was explained away as being caused by that flood and the movements of its currents.

In other words, it was a “theological” explanation, situated within a cosmology whose presuppositions included a worldwide flood sent by a creator-god to rid the earth of its sinners.

Now, of course, we have a “scientific” explanation for these layers, and a classification system which divides the existence of the earth from its beginning 4,540,000,000 years ago to the current day. That number, 4.54 billion years, is a very recent conclusion, decided either three decades ago or eight decades ago, depending on which scientific study you decide was first “conclusive.” In the early 1900’s, the consensus was that the earth was between 40 million years old and 2 billion years old (and just before that, 20 million to 400 million).

4.54 billion years is a long time ago, and it’s impossible for any of us to go back and verify the matter personally. For most of us, the age of the earth doesn’t much affect our daily lives (unless you’re a fundamentalist Christian or a Seventh Day Adventist), but the idea of geologic time has much more influence because of a defining feature of our current way of living: fossil fuels.

Fossil fuels (petroleum, coal, natural gas) are all thought to have begun to form during the geologic period known as the Carboniferous Period, which was between about 200 and 400 million years ago (these dates are often changing). The accepted theory is that vast amounts of dead swamp plants (for coal) or algae and zooplankton (for oil and natural gas) slowly decomposed under extreme pressure in layers of sediment. This changed their composition and concentrated their carbon, creating substances which produce massive amounts of energy when burned.

Of course, fossil fuels are the primary source of energy that powers modern civilization, and we only recently started using them at scale about 225 years ago. Burning them releases carbon dioxide (carbon bound to oxygen) into the air, and the general consensus is that this has caused the earth to warm, icecaps to melt, and climate patterns to change radically.

I’ve used the word “consensus” and “theory” several times in the previous paragraphs, but not because I doubt any of this (I’ve no reason to). Instead, those words recur because there is always the possibility that other theories or other consensuses will arise, since that’s how truth is determined within the scientific framework.

In fact, international scientific bodies actually meet together and take votes on these questions, just like councils of bishops and cardinals once did to decide on theological matters.

This brings us back to the matter of the Anthropocene, the epoch first officially proposed twenty-three years ago. I already quoted one part of the letter in which it was introduced, but the next part of that letter will give you a sense of how political theology relates to this:

… to assign a more specific date to the onset of the “anthropocene” seems somewhat arbitrary, but we propose the latter part of the 18th century, although we are aware that alternative proposals can be made (some may even want to include the entire holocene). However, we choose this date because, during the past two centuries, the global effects of human activities have become clearly noticeable. This is the period when data retrieved from glacial ice cores show the beginning of a growth in the atmospheric concentrations of several “greenhouse gases”, in particular CO2 and CH4. Such a starting date also coincides with James Watt´s invention of the steam engine in 1784

In other words, what those two scientists were suggesting is that this new geologic epoch started with the birth of industrial-scale fossil fuel use. The steam engine came only 15 years after the first modern factory was built by Richard Arkwright, and almost immediately, industrialists combined the two in order to create the “industrial revolution.”

This seems like a good birth date for the Anthropocene, but it’s never really been the majority opinion of scientists. Others suggested that this geologic epoch started with the birth of agriculture (the “Neolithic Revolution,” around 10-12 thousand years ago), or the birth of cities (6000 to 7500 years ago), or back further to the widespread death of mega-fauna (large animals like the mammoth) between 11,000 and 50,000 years ago.

But it looks like none of these ideas will win out. Instead, the Anthropocene Working Group, which is a small group of scientists tasked with creating a formal proposal for the Anthropocene, just voted that it actually started around 1950:

Its beginning would be optimally placed in the mid-20th century, coinciding with the array of geological proxy signals preserved within recently accumulated strata and resulting from the ‘Great Acceleration’ of population growth, industrialization and globalization;

The sharpest and most globally synchronous of these signals, that may form a primary marker, is made by the artificial radionuclides spread worldwide by the thermonuclear bomb tests from the early 1950s.

That second part, regarding the nuclear material, is derived from a sediment core sample recently taken from a lake near Toronto, where plutonium was found. This core sample was called “a golden spike” —the equivalent of a smoking gun — to prove that humans are changing the earth.

A few of the theologians — I mean, scientists — in the group voted against this conclusion, including ecologist Erle Ellis, who subsequently resigned. Part of his resignation letter reads:

To define the Anthropocene as a shallow band of sediment in a single lake is an esoteric academic matter. But dividing Earth’s human transformation into two parts, pre- and post- 1950, does real damage by denying the deeper history and the ultimate causes of Earth’s unfolding social-environmental crisis. Are the planetary changes wrought by industrial and colonial nations before 1950 not significant enough to transform the planet? The political ramifications of such a misleading and scientifically inaccurate portrayal are clearly profound and regressive. Perhaps AWG’s break in Earth history will simply be ignored outside stratigraphy. But this is undoubtedly neither AWG’s goal, nor is it the way AWG’s narrative is being interpreted across the public media.

In other words, Ellis asserts that there are political reasons for this conclusion, and that the term Anthropocene will now become generally useless. Ellis, though, is also just as informed by political concerns as the rest of the AWG: he’s a signing author of the Eco-Modernist Manifesto, a statement which insists nuclear energy is key to stopping climate change.

So, while his opposition to the 1950-ish birth-date of the Anthropocene derives from his longer view of human influence on the earth, there is another concern for Ellis and others. If the appearance of nuclear material on the surface of the earth — far from where it originated — signifies the start of the Anthropocene, then urging more nuclear power to fix the problems of the Anthropocene makes no sense at all.

To be clear, there are still a few more rounds of votes required before this idea is accepted as official scientific doctrine, but already newspapers have begun reporting on this matter as if it’s a cosmological certainty. If approved in the final steps, we’ll no doubt hear it proclaimed as an undeniable fact, rather than just a conclusion reached by several groups of scientists. And on at least one point I agree with Ellis: a 1950’s birth-date strips the Anthropocene of any real meaning.

None of this actually changes what’s been happening, nor the current state of the earth and all in it. Instead, it will affect what we believe is possible, what has caused all this mess, and what can be done about it.

As with belief in a singular god, the existence of the Anthropocene will become an article of faith, while what you believe it means —and what can be done about it — will determine whether you are a true believer or a heretic.

For a really great discussion of the other proposed start dates for the Anthropocene, plus a dazzling journey through myth and science, see

’s The White Deer: Ecospirituality & The Mythic (currently 25% off with code SUMMER)And if you’re feeling a bit depressed about the environment, go get

’s book: At Work In the Ruins: Finding Our Place in the Time of Science, Climate Change, Pandemics and All the Other Emergencies.And if you like my work, pick up an annual subscription at a discount.

And please consider sharing this post!

Islamic scholars suspected this tale was mythic, rather than literal, much earlier.

I don't think it's wrong to compare science and religion but I do think you are being a bit unfair here. I think that a council voting in this way is silly but understandable. I don't think it's fair to suggest it's the same as a council voting on whether the Son is of the same essence as the Father, or on whether fossil fuels really do come from fossils. Because, as Benn says below, the boundary between Holocene and Anthropocene is like the boundary between red and orange and that's the only reason scientists feel they can vote on it. They aren't quite claiming the authority that bishops claim. It's more a liturgical than a theological point, I think.

That said, AFAIK we only think red and orange are different colours because Newton wanted there to be seven colours for alchemical reasons. Although he failed to get 'indigo' and 'violet' separated for anything other than the spectrum itself; you don't get indigo and violet crayons - just purple.

In that context, setting 1950 as the start date is definitely going to cause problems; although probably less than if we set it to 'dawn of agriculture' or 'start of colonial expansion' because a lot of people actually do believe that those points mark 'when it all went wrong'; whereas nobody can seriously believe 1950 was when the Beast suddenly popped out of the sea.

Personally, I'm very much in the holocene = anthropocene camp; as I work on large mammal conservation, I kind of have to see it that way. But I suppose we can just start talking about 'the long Anthropocene,' like people do with centuries.

I suppose it might be possible to argue that the IPCC marked a sort of 'council of Nicea' moment; though without a single emperor who was very obviously on side. I think the IPCC has done a lot to introduce the dangerous idea of 'scientific consensus', which could be considered an oxymoron.

Start and end dates for things are always discretionary. When does red end and orange begin in a rainbow? Time flows, so picking a point in it is a fallacy, and is only needed if useful in some way, like if you want to blame something for the shit we're in.

I can't remember the publication but there is an essay by Bernard Charbonnau on the Ellul forum about the Christian roots of modernity. Just replaced Christ with The Science as redeemer, with hilarous consequences all around. I reckon it's black magic, myself. Newton and all those cool kids back in the day were alchemists and sorcerers.