"No One"

Greece Travel Journal, Part Four

Previous entries in this journal series:

Prologue

I was 13, I think, living in a house with barely-working air conditioning in south Florida. We had roaches constantly in the house, and swarms of ants, and my sisters and I had all gotten a rather unpleasant parasite called pinworms, and it was just a really awful time.

We rented this house from my uncle, who — as far as he had told us, anyway — had bought it specifically so we could live in it. After my parent’s divorce, my developmentally-disabled (and soon to become schizophrenic) mother had moved us to Florida to live with her brother and his family. It all sounded quite nice, actually, except once we’d gotten there, we soon understood he’d never actually wanted us there.

Their father, my grandfather, had insisted my uncle take us in because we had nowhere else to go. He begrudgingly agreed, but neither he nor his wife could ever hide their contempt and outright disgust for us. We had the manners of the poor, all our stuff was packed in trash bags, and our clothing was in tatters. I’d not been bought a new pair of underwear or socks since I was 8, and I was now 12, and I didn’t actually know that people usually owned clothing that fit them and didn’t have holes so big you could put them on incorrectly and barely notice.

We weren’t there for long, six months, maybe. There’d been some fight between my mother and my aunt, a shrill and frigid woman, who, four years later, at my other uncle’s funeral, thanked me for “not ruining this for everyone like you always do.” Apparently, that fight involved physical violence, and we were suddenly told we’d be moving into our “own” home. This felt great (despite its location and relentless insect infestation) but didn’t last long either.

A year after we’d moved in, my uncle told me he was kicking us out because I hadn’t mowed the lawn in a month. He’d asked me to mow it the week before, and I didn’t. I was a 14 year old kid, and didn’t want to mow the lawn, and didn’t like him telling me what to do. “You’re not my father,” I told him.

“You’re not my renter anymore, either. Good job — you just made your family homeless.”

Actually, he’d meant to flip the house, to resell it at a much higher price. His entire reason for buying the place was to do this, but he was only able to get the extra money from my grandfather to buy it by telling him it was for us instead. I didn’t know any of this at the time, though. In fact, it wasn’t until I was 30 that I finally learned that, no, actually, I hadn’t actually forced us into potential homelessness. He just wanted to make money and needed an excuse.

I’m thinking about that house and its deep misery because I’ve finally started to understand precisely when it was that I became a Christian. When I was 7 until about 11, before my parents divorced, I’d gone to a bizarre and small evangelical cult in Ohio, the Churches of Christ in Christian Union. Some weird stuff happened to me there, and also some really bad stuff in the month-long summer camp attached to that sect. I have some strange sexual memories involving deacons there that I cannot really re-assemble into reliable remembrance, and I was “sanctified” in a strange ceremony that I’m pretty sure fucked me up for decades — but that’s not how I chose to believe in Jesus.

And yes — I chose to. Choice, of course, rarely ever involves actual freedom and full knowledge of what those choices entail, but as best as I could, I chose to believe in Jesus.

That happened while I was living in that roach hotel of a house. We’d find them in our breakfast cereal, in boxes of rice or pasta. They’d run across the carpet at all hours of the day and night, barely even bothering to scurry away. Yes: we used baits, and sprays, and powders, and constantly cleaned with bleach and ammonia (and foolishly sometimes both at once), but nothing worked. The house was hardly sealed against the outside, and we lived in a dredged swamp, and there was really nothing else we could have done. Getting us kicked out of there might have been the only real solution to it all, but again, that’s not even how that really happened.

I was a deeply sad and desperately lonely kid. Everyone saw that, I’m sure of it. A neighbor woman convinced her husband to take me to a Boy Scouts meeting, but I was so awkward there that he never brought me back a second time. The school bus driver who picked me up every day always asked if I was okay and tried to teach me how to make friends, but that never seemed to work.

My mother had started going to “singles bible study night” at a church because she was also lonely, and then one day she brought her kids — us — to a youth group meeting at their insistence. People were nice to me there. The youth minister talked to me like I was interesting, and there was free pizza and we were really poor, so we went again.

And then we went to another event, and I don’t know how it happened but I started crying and couldn’t stop. The youth minister gave me a hug, told me he knew “it must be really hard,” and then told me that Jesus could make everything better. Jesus could be my best friend, and “God” could be a better father than the one who abandoned me, and also I’d get to go to heaven instead of hell, so would I like to accept Jesus into my heart right now?

Jesus fucking Christ that was a shit trick, but fucking hell it worked.

I got baptised a few weeks later, and was given a youth study bible with my name engraved on the front, and suddenly everything had purpose and meaning. I went to church twice every Sunday morning, every Sunday evening, every Wednesday evening. Then, I started also going on Tuesday evenings, which is when they sent people out in groups to convince others to come to church, too. I devoured the Bible, reading it all the way through that first year and two more times by the second year. I memorized the book of John, and the first few chapters of Genesis, and then, to my extreme detriment, the Book of Revelation.

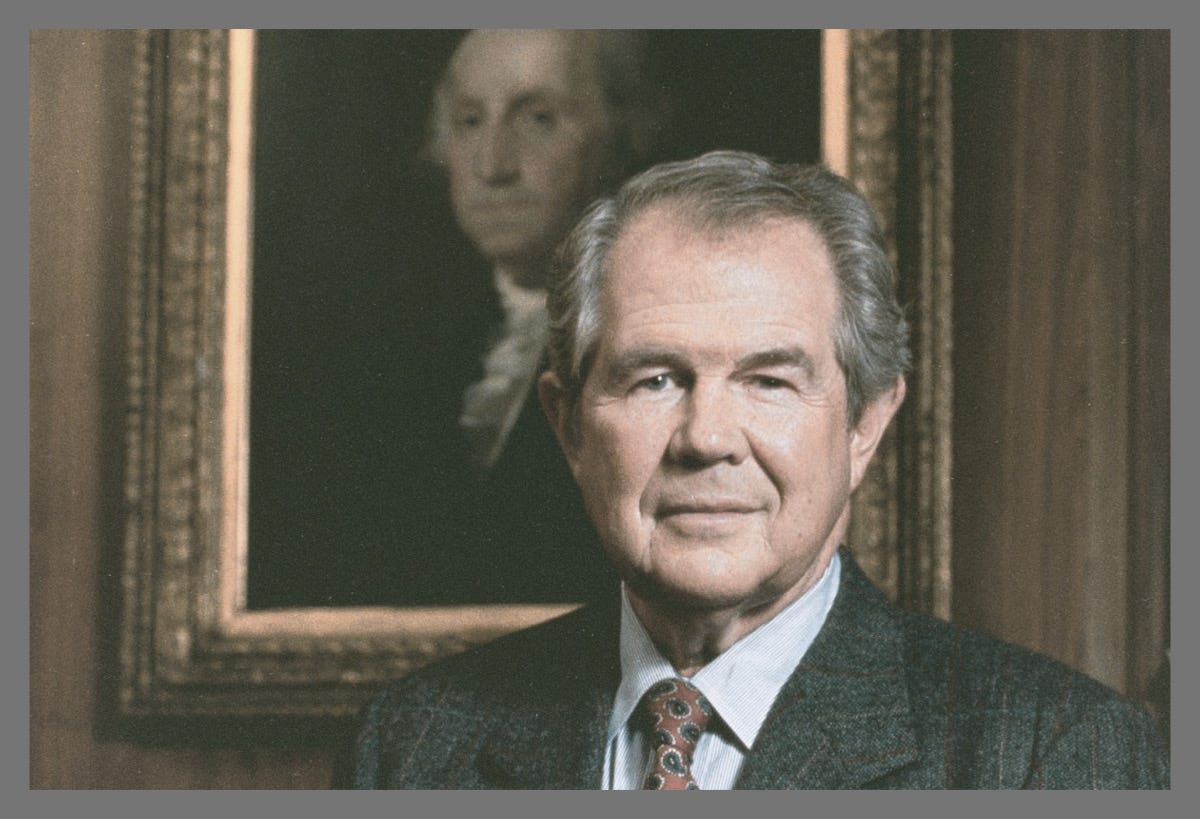

I have a man called Pat Robertson to thank for that last bit. I’d found the 700 Club one evening flipping through television channels, and even though it at first seemed a bit weird and boring, I couldn’t look away. Pat was doing a special episode about the End Times, and there was a toll-free number I could call for a booklet that would help me survive the Tribulations. I called, of course, and it showed up a few days later.

If you’ve no experience with Protestant Christianity, you might not know that there’s a bit of a schism about a thing called the “Rapture.” It’s the event described in Revelation where the Christian god takes up believers to heaven, and the disagreement is about whether this happens before all the plagues and torments on earth happen (“pre-trib”), after that all happens (“post-trib”), or during (“mid-trib”). The ridiculous Left Behind book series, as well as the bumper stickers declaring “In case of Rapture, this car will be unmanned” (and its counter: “In case of Rapture, can I have your car?”), as well as the internet contingency plans to care for pets or to send out automated messages to unsaved loved ones, all derive from the dominant “Pre-Trib” idea.

Pat Robertson, on the other hand, was one of the dominant voices of the “Post-Trib” rapture scenario. In that view, Christians would be hunted down, forced to starve because they won’t accept the mark of the beast, and suffer all manner of other torments during the reign of the Anti-Christ and his false prophet. Thus, watching for signs that the End Times have already started is not just a curiosity but an urgent necessity for such Christians, since they are told repeatedly by the Bible that they must be ready.

My church taught that the rapture would happen before the tribulations started, that we’d all be caught up suddenly, disappeared from the earth, while all the unbelievers — including many who mistakenly believed they had been saved — would be left to endure the wrath let loose by the Christians’ god. Pat Robertson taught the opposite, and I wasn’t sure who to believe because the writings of John of Patmos didn’t really make this clear.

I became obsessed with this question, which is why I started memorizing the Book of Revelation. This, of course, made me worried and even quite paranoid. No sane person can ever have that stuff stuck in his head like that and still remain sane.

I remember the day clearly. I’d stayed home from school, but my sisters had gone. My mother had gone to her job at Burger King, an employment she ended up not being able to hold down for more than a few months. I was alone at the house, alone with the roaches and the ants and no television to distract me because my mother hadn’t paid the electric bill and it was shut off.

For some reason, the street outside was completely silent, and none of our neighbors were home because they were all at work, so the world felt dreadfully still. A thought came into my head, and I couldn’t make it go away. I looked outside at the empty street, tried the television though I knew it wouldn’t work, and even picked up the phone. There was no sound when I put it to my ear, not even a dial tone.

The rapture happened, and I got left behind.

I panicked. I cried. I prayed, and then I prayed again. Perhaps Jesus hadn’t taken me because I’d thought dirty thoughts about men, or maybe because I’d lied about being sick so I could stay home from school that day. I’d thought I was saved, but here I was abandoned, scared, and fated to endure all the horrible plagues and pestilence and rains of fire. I’d be forced to get the mark of the beast, to follow the Antichrist, to live out my last days in a fated march towards a lake of fire and brimstone and there was nothing I could do about it now.

I cried and prayed for hours, too paralyzed with fear to leave the house so to see which seal had been broken or trumpet blown, or even to verify that people had really been raptured at all. Hour upon hour of this abject terror passed until my mother came home, confused why I was such a mess.

“I didn’t pay the phone bill yet,” she said, explaining why the line hadn’t worked.

“I thought I had more time.”

9 June, part one

Pat Roberston died while I was on the island of Patmos. In fact, I found out he died while I was sitting in the village of Skala, drinking a blueberry-flavored kefir, waiting for my husband’s ferry to arrive.

I thought about Pat Robertson’s death glancing at emails at a restaurant looking out over the harbor. We had several hours before my husband could check-in to his AirBnb, a somewhat remote and run-down house just next to the ocean. The host’s communication was quite shady, and she’d delayed the time he could enter several times. By itself, this wouldn’t have been too stressful, but my husband hadn’t slept enough, had injured his foot, was deeply stressed by everything in his life before this trip and also by the journey. I had to manage his frustration along with my own, and it felt a bit overwhelming.

“Pat Robertson is dead,” I said to him, hoping to distract him from his impatience.

“Who was Pat Robertson?” he asked, and I immediately realized that, of course, he’d have no reason to know who he was.

As for the squid cult’s apocalypse in Mieveille’s Kraken, the Christians’ End Times has constantly spilled out from its peculiar sect into the rest of the world, pulling us all in, and Pat Robertson is one of the primary men who’ve helped it do so.

Many Christians believe that certain conditions need to occur before Jesus is able to come back to earth. One of those is that their gospel must be proclaimed “to every nation,” which many take to mean that the Christ will only come back once every living human has had the chance to convert to Christianity. This is one of the core drives of the massive and heavily-financed missionary efforts to remote regions of the Amazon and to Africa. The “Gideons Bible,” which could for many decades be found in the drawer of every motel room in America, is also part of this drive, as are the linguistic training centers meant to help missionaries learn rare languages into which they can later translate the bible.

As far as most evangelicals are concerned, a second condition has already been fulfilled. That happened with the peculiar help of Adolph Eichmann and other Nazi officials and theorists, along with large sums of money paid by the United States and the United Kingdom.

That condition was the founding of the State of Israel, which, according to most readings of Revelation, must exist before the tribulation can occur. This is the reason why there has always been so much support for Israel in the United States. It’s never been that American Christians care particularly for Jews (in fact, they really don’t), but rather that the Jews must have a homeland in order to trigger Christ’s second coming. Some even believed that Yasser Arafat was an agent of the Antichrist, and many still believe Russia’s less-than-friendly relationship with Israel is a sign that the Antichrist will be a Russian leader. Others think he’ll come from the European Union, or the United Nations.

I mentioned the Nazis had a hand in all this, a point which startled me endlessly when I stumbled upon it. Just as American Christians care little for Jews, Nazis cared nothing at all except for one important point. Several theorists had become obsessed over the matter of the katechon, “that which restrains.” It seemed clear to them that the Jews were the linchpin which kept closed the gates of a second coming which, for the esoteric Christian political theology of Carl Schmitt and others, meant not the actual return of Jesus but the full manifestation of the Third Reich on earth. The only debate was whether or not the Jews needed to be exterminated (Carl Schmitt’s final conclusion) or fully banished back to their original place of origin. This is why Eichmann was sent to Jerusalem to negotiate a resettlement plan.

There are many, many, many other ways where the Christians’ apocalypse has influenced the world, its geopolitics, its cultural manifestations, its laws, and especially its inhabitants. The certainty that Jesus’s return might be any day now has been used repeatedly as not just an excuse but a reason not to enact any regulations or curbs on fossil fuel use, resource extraction, and pollution. Why try to protect nature when the bible already tells us it will all be destroyed in floods and fires? In fact, often the actually-occurring floods and fires are seen as signs the prophecies are being fulfilled; therefore, why try to close the seals and unsound the trumpets that “the LORD” has ordered unsealed and sounded?

Pat Robertson was not the only figure shaping this eschatological view of climate change and environmental collapse, but he was its strongest voice for many recent decades. Despite fleeing Christianity and becoming a pagan, for years after I found myself unable to stop looking for those “signs and wonders.”

Later, I found myself watching the 700 Club again, this time with a constant eye on how the Apocalypse shaped the Christian support for George W. Bush’s invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq. Bush had filled key cabinet and department head positions with Christians who believed just as Pat Robertson did, most notably the first head of the Department of Homeland Security, John Ashcroft. While the rest of us shook our heads at the absurdity of these increasing laws and invasions, countless Christians prayed for more of it so as to hasten the day of Jesus’s return.

Decades later, sitting on the Isle of Patmos, the “Island of the Apocalypse,” all this flooded back to me. The way the End Times had shaped so much of the world was a macrocosmic mirror to how much it had shaped so much of the microcosm of my younger mind and soul. It was all a nightmare from which I never felt able quite to waken; thus, listening to others speak of Mad John as if he’d gifted the world some great truth was quite difficult to countenance.

And yet, I smiled.

Pat Robertson died while I was on the Island of Patmos, the island said to be “most sacred” to Artemis. I was there with a group committed to new ways of relating to each other, to finding ways of connecting to our own and to others deepest humanity, to finding a new “revelation.” While waiting for my husband’s arrival, sitting by the shore with my blueberry kefir, I learned Pat Roberston had breathed his last choking breath.

My husband looked at me while I thought on all this. He was still waiting for my answer to his question, “who was Pat Robertson,” and I smiled again, silently thanking the gods and spirits of the island, and especially Artemis, and answered:

“No one.”

So sorry you had to go through such a difficult childhood. Absolutely eye opening about the reach of the Christian tentacles , I’ve heard bits of it before but this was a good reminder of how fucked up humans can be. And you sir, to go through all this and survive it and somewhat come out the other side, scars, trauma and all, is a reminder of how good humans can be. Thank you

Incredibly moving and emotional journey, a longing to discover the world and one's inner peace and beauty.